The Toronto Jewish Film Festival, one of the best of its kind, gets under way on April 30 and runs until May 10.

A preview:

Veronique Lagoarde-Segot’s Shoah: The Forgotten Souls of History, is a hard-hitting and important documentary about the role of cinematography in Soviet propaganda during World War II.

Regarding cinema as a tool to foster national unity and forge an inextricable bond between the state and the people, Moscow dispatched teams of cinematographers to the front following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941.

Although the Red Army was basically in retreat in the first two years of the war, the cinematographers were under strict orders to bring back footage that would lift morale. The Soviet leadership preferred positive images of Soviet heroism, or graphic ones of German corpses rotting away and the debris of German tanks and artillery pieces strewn on the battlefield.

As this divorced-from-reality footage was released to the public, Germany conducted a scorched earth campaign, demolishing villages, killing civilians and exterminating Jews on an industrial scale. The Germans had no problem filming graphic pogroms in Ukraine and Lithuania, but Soviet cameramen flinched from recording such massacres.

In keeping with this politically correct formula, Soviet propagandists described Jewish victims of Nazi ethnic cleansing as “Soviet civilians.” It was not until 2001 that Moscow finally acknowledged the 33,771 Jewish victims of the 1941 Babi Yar pogrom in Kiev.

The war, the film states, was a Soviet affair in which Jews per se had no place. The reasons are clear. Moscow was loathe to admit that Soviet citizens had collaborated in the mass killings of Jews. Nor did Moscow want to validate the fantastical Nazi claim that Bolshevism and Judaism were entwined.

When the Red Army reconquered territory that had been held by Germany, Soviet cameramen turned a blind eye to Nazi atrocities in which Jews had been the chief victims. With Moscow once again demanding heroic rather than tragic images, Soviet cinematographers focused on courageous partisans.

The Jewish identity of Zoia — a partisan of valor who had been hanged by the Nazis — was suppressed, while Soviet newspapers referred to Jews who had been murdered by the Nazis as “peaceful citizens.” To add insult to injury, crosses were planted on the mass graves of Christian and Jewish civilians.

After the Red Army had liberated Auschwitz, Moscow trumpeted the liberation in staged footage. Already infected by a rising spirit of Russian chauvinism and antisemitism, the Soviet Union chose to ignore the fact that most of the camp’s victims had been Jewish.

***

The piece de resistance of Warsaw’s Museum of the History of Polish Jews is a painstakingly-built replica of the ceiling of an 18th century wooden synagogue the Nazis destroyed in the town of Gwozdziec, now in southern Ukraine. The ceiling, painted in vivid colors, is an amalgam of Hebrew texts and letters and real and mythic animals. It’s truly spectacular, a thing of beauty.

Its reconstruction is the subject of Yari Wolinsky’s Raise the Roof, a heart-felt documentary that captures the spirit of the project. It’s not only about the arc of Jewish history in Poland, which is both illustrious and tragic, but about the intricacies of true craftmanship.

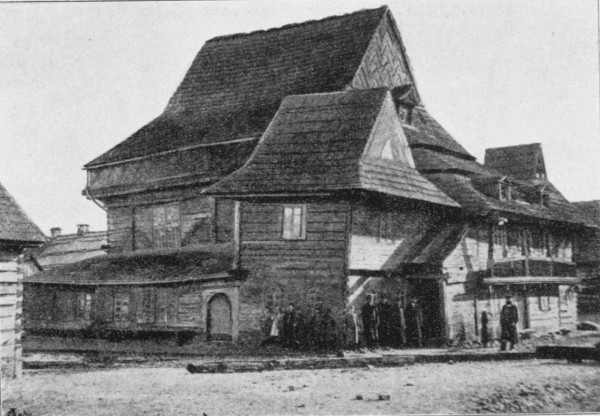

Construction of the synagogue began in the 1680s, when Gwozdziec was located in the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth, a hotbed of Jewish liturgical art. It would be one of some 200 wooden synagogues built throughout greater Poland. During the Nazi occupation, every single one was pillaged and levelled.

A few years ago, Barbara Kirshenblatt Gimblett — a curator at the museum and the daughter of Polish Jews who had settled in Canada — hired an American couple to rebuild the ceiling. She chose Rick and Laura Brown, specialists in the replication of historic objects and artifacts, because their vision coincided with hers. The Browns, who are neither Jewish nor Polish, recommended that the ceiling of the Gwozdziec shul should be replicated because it had the best documentation. On their suggestion, a roof would be added.

Visiting Poland, the Browns discovering that Jews had worked closely with Polish craftsmen in the construction of the wooden synagogues. They then proceeded to build a large-scale model of it, complete with a full-size bimah. In their quest for authenticity, they worked with the tools and techniques of the 18th century.

Apart from employing 25 professional timber framers, they used the voluntary services of students from a variety of countries, including Poland. The film charts their progress in minute detail, and it’s never less than interesting.

It took them two weeks to install their masterpiece of design, carpentry and architecture in the museum, which opened last autumn to critical acclaim. Laura Brown is satisfied with the outcome, as she should be. Reconstruction is a hard and slow task and requires teamwork and passion. These were the qualities that were brought to bear to recreate the ceiling of a wooden synagogue from a vanished world.

***

Ivan Nichev’s Bulgarian Rhapsody, the final installment of a trilogy of films on the Jews of Bulgaria, takes place in 1943 as Bulgarian Jews come under increasing antisemitic pressure from Bulgaria’s fascist government.

Aligned with Nazi Germany in an alliance of convenience, Bulgaria imposed a raft of restrictions on its 50,000 Jewish citizens, but stopped short of deporting them to their deaths in German extermination camps in Poland. Bulgaria, however, acceded to German demands to deport 11,343 Jews from Bulgarian-occupied Thrace and Macedonia. It’s a terrible blot on Bulgaria’s image, but at least Bulgaria protected Jews of Bulgarian nationality.

Nichev’s film revolves around the friendship between two young men, Moni (Kristiyan Markarov), a Jew, and Giogio (Stefan Popov), a Christian. They enjoy each other’s company and compete for the affections of Sheli (Anjela Nedyalkova), a fetching Jewish woman from a lakeside resort in Thrace.

The film, in the very first scene, establishes the antisemitic atmosphere prevailing in Bulgaria. Moni, a yellow Star of David label affixed to his lapel, is rudely ejected from a crowded room by a policeman. The Jewish curfew has begun, the cop says.

Moni lives at home with his father, Moise (Moni Monoshov), sister Mazal and grandmother Fortune. They’re acutely aware that the curtain is coming down on the Jewish community, but they try to carry on as usual. Mazal upsets Moise when she announces her intention to marry her boyfriend, Isak. Moise objects because he wants a son-in-law who’s a “man of influence.”

The anti-Jewish motif returns in a scene that unfolds in the Department of Jewish Affairs. Dannecker, the SS representative in Bulgaria, berates Belev, the Bulgarian official in charge of implementing antisemitic measures. “Why are things moving so slowly here?” he asks impatiently.

A chastened Belev proceeds to reprimand an aide, asking why the Star of David label worn by Bulgarian Jews is so small and inconspicuous. Venting yet more steam, as Allied bombs fall on Sofia, Bulgaria’s capital, Belev blames Bulgarian Jews for having embroiled Bulgaria in the war.

The Jews of Bulgaria are not subjected to physical violence, but their second-class status is a source of pain and humiliation. As an elderly Jew tartly observes, the world is divided into countries where Jews are forbidden to live and where they’re refused entry.

Midway through Bulgarian Rhapsody, the police confiscate the radios of Jews. Giogio’s father, an official in the Department of Jewish affairs, orders him to sever ties with Moni, but he refuses. Giogio’s refusal is part of a larger process of Bulgarian refusal to comply with all of Germany’s demands with respect to Jews. Indeed, Belev informs Dannecker that thousands of Bulgarians are opposed to antisemitism.

This may be true, but some Jews, like Mazal, have lost their faith in Bulgaria. She and Isak announce they’ve booked passage on a ship bound for Palestine.

Bulgarian Rhapsody exposes the tragedy that enveloped the Jews of wartime Bulgaria. Nichev coaxes fine performances from his cast, but his film is flaccid in terms of pacing and intensity.

Michael Verhoeven’s feature film, Let’s Go!, focuses on a Jewish family that sets down roots in West Germany after World War II. The Stegers are Polish Jews who found themselves in Germany in the wake of the Holocaust and remained there, like thousands of Jewish survivors from eastern and central Europe.

Majer (Maxim Mehmet) and his wife, Hela (Katharina Nesytowa), though traumatized by their mistreatment during the war, are determined to start a new life in the country that persecuted them. While Majer’s brother and his wife immigrate to the United States for a fresh start, Majer and Hela open an inn in a small town in Bavaria.

They’re Jews in the privacy of their home and among fellow Jews, but in public, they conceal their Jewishness, pretending to be Germans and instructing their first daughter, Laura, to do the same. Laura grows up as a conflicted and rebellious person, marries a childhood friend and resettles in Los Angeles.

The film shifts back and forth in time, starting in 1947, when Hela is pregnant with Laura, and coming to a close in 1968, when Laura (Alice Dwyer) returns to West Germany for her father’s funeral. It’s apparent that Laura and her mother have had a poor relationship, possibly because Laura resents the way in which she was brought up.

The film’s title is a reference to a phrase an American soldier used when he liberated Majer from the Dachau concentration camp.

Let’s Go! explores an issue in postwar German Jewish life that most Jews would rather have swept under the rug. Thanks to Verhoeven’s directorial skills and a plausible cast, the film leaves us with a lot to mull over.