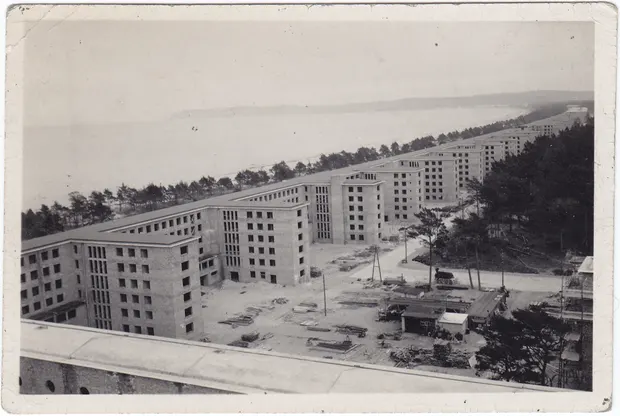

Prora, a Nazi resort in northeastern Germany, was intended to be the world’s largest vacation playground. Consisting of eight functional buildings stretching 4.5 kilometers along the sandy shore of the Baltic Sea, it was designed to accommodate 20,000 vacationers.

Construction was halted when World War II broke out in September 1939, dooming Prora to oblivion as a resort/sanitorium. During the war, German armed forces were stationed there. And during East Germany’s existence as a communist state, Prora was repurposed as a military base.

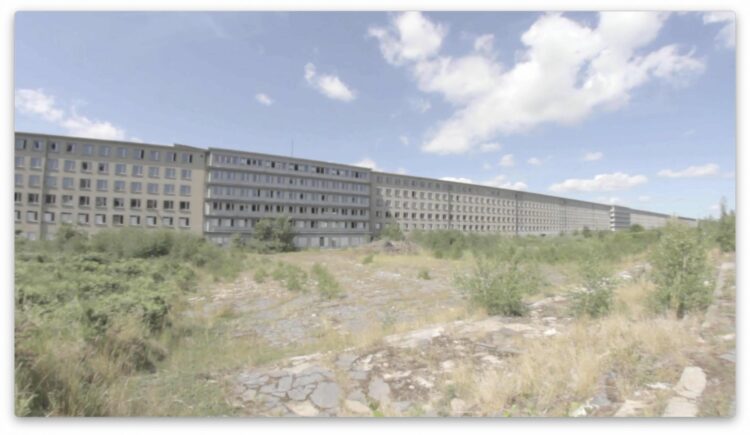

In recent years, real estate developers have converged on Prora to construct condominiums, apartment buildings, hotels, spas and a youth hostel.

Prora’s convoluted history is examined by Mat Rappaport in his substantive documentary, Touristic Intents, which explores the connection between architecture and politics in Nazi Germany. His 82-minute film, an amalgam of file footage and talking heads, opens in Los Angeles on June 12.

Prora was the brainchild of Robert Ley, the leader of the German Labor Front, whose mission was to enlist the working class into the Nazi political system.

Ley was a vulgar, violent antisemite who exemplified “the coarse, corrupt face of Nazism,” according to the Dictionary of the Third Reich. Yet he was astute enough to realize that cheap, all-inclusive holiday packages geared to the needs of ordinary workers could help the Nazi regime gain traction and attain further legitimacy. Ley’s overarching goal was to prove that travel would no longer be an upper-class privilege.

Modelled after similar resorts in Britain, Prora was built within the framework of Ley’s “Strength Through Joy” program, and was intended to be a beacon in the field of leisure.

Designed by the architect Clemens Klotz, Prora was unique in the sense that all its rooms faced the sea.

It was still under construction when the war erupted, which meant that Ley’s vision went unrealized. He committed suicide while in detention after Germany’s defeat in the war.

During the East German era, conscientious objectors were sent to Prora as punishment. With the reunification of Germany in 1990, Prora fell into disrepair and was not even marked on maps. In the past few years, however, developers have gentrified Prora and converted it into a prime tourist destination favored primarily by Germans.

Rappaport believes that Prora should not be vilified simply because it was conceived as a Nazi project to burnish the stature of Adolf Hitler’s racist regime. As he suggests, buildings themselves are not “guilty” of any crime.

His point is well taken, and Touristic Intents underscores it.