It may surprise some that the infamous Hollywood blacklist, the subject of Trumbo, was almost single-handedly broken by the director of Exodus, the blockbuster movie about the birth pangs of a new nation, Israel.

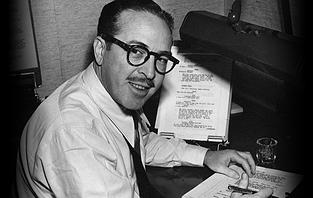

Trumbo, which premiered at this week’s Toronto International Film Festival, revolves around Dalton Trumbo, the screenwriter whose high-flying career was shattered by the wave of anti-communist hysteria that inundated the United States during the early phase of the Cold War.

Trumbo’s screenplays — Thirty Second Over Tokyo and Kitty Foyle, to mention but two — established him as a master craftsman. But once he had aroused the suspicion of witch hunters in Washington, D.C., he was doomed.

The object of suspicion and loathing in certain circles due to his advocacy of workers’ rights and his membership in the American Communist Party, he joined the party in 1943, when the United States and the Soviet Union were allies in a wartime alliance battling Nazi Germany and the Axis powers.

Subpoened by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947, Trumbo was cited for contempt of Congress after refusing to answer “yes” or “no” to a series of pointed questions concerning his political beliefs.

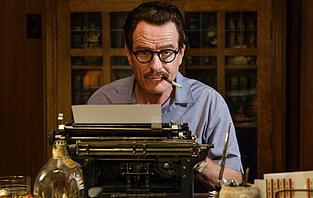

Trumbo, ably directed by Jay Roach, stars the irrepressible Bryan Cranston (Breaking Bad) as the blacklisted screenwriter who was victimized by a climate of fear and intolerance. It focuses on the period between the late 1940s and early 1960s, when Trumbo struggles to earn a living as a pariah in his own country. Often, he’s seen banging out and pasting together screenplays in a bathtub, one of his favorite working venues.

Trumbo, in short order, moves beyond the theme of an iconoclast whose unpopular views earned him ostracism and grief. The film, enlivened by John McNamara’s literate script, is a sharp critique of a callow government that succumbed to paranoia and subverted the constitutionally enshrined democratic rights of American citizens.

It’s unclear in the movie whether Trumbo was still a member of the Communist Party after the war. But as far as his enemies in Hollywood were concerned, he was a “dangerous radical,” as the right-wing gossip columnist Hedda Hopper claimed.

To his other detractors, who may have been jealous of his success, Trumbo was a “swimming pool socialist” who talked like a radical and lived a life of princely ease. As one of Hollywood’s best paid screenwriters, he enjoyed the comforts of the American dream. But after being labelled a subversive, he was cut adrift, becoming a victim of tyranny and intolerance.

Trumbo, naively perhaps, believes that freedom of expression is guaranteed by the First Amendment. The conservative actor John Wayne (David James Elliott) disabuses him of that notion. “It’s a new day,” he declares. “Wake up!” In archival newsreels, the actors Ronald Reagan and Robert Taylor echo that conventional mantra.

Convinced that Hollywood is infested with Red traitors and spies, Congress forces Trumbo and nine of his colleagues — the Hollywood Ten — to testify.

As these events transpire, the imperious Hedda Hopper (Helen Mirren) warns a Jewish studio mogul to sack his communist employees. When he hesitates, she launches a vicious antisemitic tirade, calling him a “kike.” Hopper’s cynical ploy works. Trumbo is discharged, forcing him to sell uncredited scripts to bottom-feeding producers. One of his screenplays, Roman Holiday, starring Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn, turns out to be a mega hit, as well as an Oscar winner.

Having been found guilty of contempt, Trumbo is imprisoned, a prison guard subjecting him to a humiliating strip search after he presents himself at the jail. The actor Edward G. Robinson (Michael Stuhlbarg) shares Trumbo’s utopian ideas, but, having been unemployed for a year, he cooperates with the committee, thereby earning the approval of right-wingers.

Upon his release, Trumbo finangles work as a screenwriter. His boss, Frank King (John Goodman), pays him peanuts to crank out scripts under a pseudonym, but he’s satisfied with the arrangement because it enables him to support his wife (Diane Lane) and three children, one of whom is portrayed by the alluring Elle Fanning. Inevitably, Goodman is pressured to fire Trumbo.

Trumbo can hear the blacklist crumbling under the weight of its absurdity when one of his scripts, written under an assumed name, wins an Academy Award, and when the actor/producer Kirk Douglas (Dean O’Gorman) asks Trumbo to write the screenplay for his next film, Spartacus.

The director Otto Preminger (Christian Berkel) soon comes calling. Can Trumbo write the script for Exodus? Preminger regards Leon Uris’ best-selling novel on the establishment of Israel as “a perfect piece of shit” concealing a good story. Satisfied with Trumbo’s treatment, he gives him a credit line, thus liberating him from the shackles of the blacklist.

Trumbo, which is effervescent and grim by turns, recreates a time and a place which is best left behind in the dust but which should never be forgotten. It was a black era when America played fast and loose with civil liberties, much to its eternal shame.

Trumbo distills that spirit with elan and finesse.