The Iran nuclear agreement, the object of Donald Trump’s withering wrath, could well be in jeopardy.

The U.S. president has denigrated the accord, signed by Iran and six major powers in Geneva in the summer of 2015, as “one of the worst deals I’ve ever seen.” Furthermore, he has threatened to abandon it unless it is reconfigured to his standards.

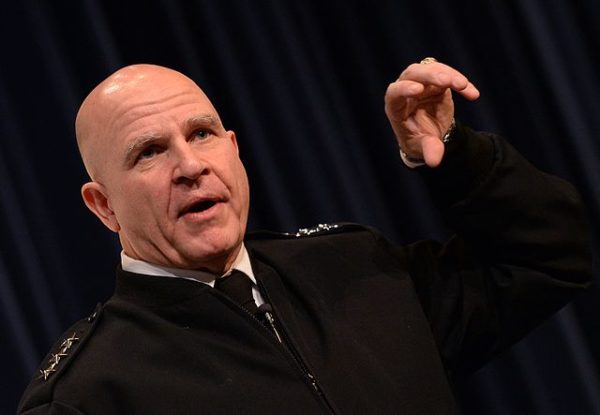

Under intense pressure from his closest advisors, including Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Secretary of Defence Jim Mattis and national security advisor H.R. McMaster, Trump stepped back from the brink this past July when he grudgingly agreed to certify Iran’s compliance with the accord, which curbs its nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief.

The question now is whether he’ll certify the agreement on October 15, when the next deadline for certification occurs. “You’ll see what we’ll be doing in October,” he said coyly. “It will be very evident.”

As Tillerson said on September 19, Trump may choose to walk away from it unless Iran is willing to renegotiate it, which is unlikely.

At the United Nations, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said that the Islamic Republic of Iran would not be the first country “to violate the agreement, but will respond decisively and resolutely to its violation by any partner.”

Last month, he warned the United States that Iran could restart its nuclear program within a matter of hours should Washington impose further sanctions. Despite Rouhani’s threat, Trump, on September 14, imposed new sanctions on eight Iranian entities and nine individuals, while the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill banning the sale of replacement airplane parts to Iran.

Trump claims that Iran is violating the “spirit” of the agreement through its missile testing program and its military adventurism in the Middle East. Iran’s influence in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen and the Gaza Strip is certainly increasing, but the nuclear agreement was not designed to deal with these contentious issues.

Addressing the United Nations General Assembly on September 19, Trump lambasted the agreement, negotiated by his predecessor, Barack Obama, as a national embarrassment. As he put it, “We cannot abide by an agreement if it provides cover for the eventual construction of a nuclear program. The Iran deal was one of the worst and most one-sided transactions the United States has ever entered into. Frankly, that deal is an embarrassment to the United States.”

Since it was ratified by the Obama administration as an executive order rather than as a treaty, Trump has the authority to scrap it, leaving Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany to salvage it. Reflecting the preference of these countries, French President Emmanuel Macron has called the agreement “solid, robust and verifiable,” and warned that its renunciation would be a “grave error.”

The chairman of the influential U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Bob Corker, a Republican, basically agrees with Macron’s assessment.

In all likelihood, the cancellation of the agreement would heighten tensions between the United States and Iran, on the one hand, and Israel and Iran, on the other hand. It could even lead to a war in the Middle East.

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency, Iran has fully complied with the agreement. Iran has exported its highly enriched uranium to Russia, one of its chief allies. Iran has also eliminated 98 percent of its stockpile of low-enriched uranium.

Iranian enrichment activity is limited to 3.67 percent, the accepted level for reactor fuel, and Iran has stopped enriching uranium at its Fordow underground facility. Iran has disabled and poured concrete into the core of its plutonium reactor, thereby shutting down the plutonium and the uranium pathways to nuclear weapons.

As well, Iran has whittled down the number of its centrifuges, used to enrich uranium, from 19,000 to 6,000. The remainder have been dismantled and are subject to rigorous international monitoring. At its nuclear facilities, uranium mines and centrifuge rotor production factories, Iran has submitted to constant and intrusive supervision by International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors, cameras, and monitoring equipment.

In addition, Iran has accepted limitations on its research and development activities, and the import of sensitive materials is monitored.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, one of the chief critics of the agreement, is skeptical about these safeguards. “This is a bad deal — either fix it or cancel it,” he declared recently.

Netanyahu believes that its so-called sunset clause, which will lift all restrictions on Iran’s nuclear program once the accord expires in 10 to 15 years, is extremely problematic.

Speaking at the United Nations on September 19, he warned: “When that sunset comes, a dark shadow will be cast over the entire Middle East and the world, because Iran will then be free to enrich uranium on an industrial scale, placing it on the threshold of a massive arsenal of nuclear weapons.”

Netanyahu contends that “crippling sanctions” should be imposed on Iran fully unless it dismantles its nuclear weapons capability. “Fixing the deal requires many things, among them inspecting military and any other site that is suspect, and penalizing Iran for every violation. But above all, fixing the deal means getting rid of the sunset clause.”

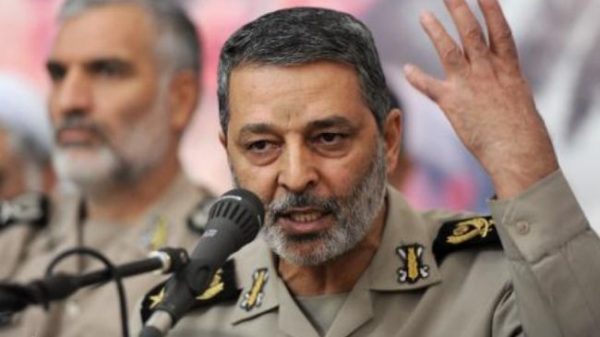

Netanyahu contends that Iran’s ballistic missile program is a potential threat to Israel. On September 18, Iran’s newly-appointed army chief of staff, General Abdolrahim Mousavi, warned that Haifa and Tel Aviv “will be razed to the ground” should Israel make “any wrong move.”

Netanyahu claims that the nuclear accord, rather than having curbed Iran’s regional ambitions, has increased its military profile in the Middle East. Iran supports a constellation of allies hostile to Israel and the United States — the Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad, Hezbollah, Hamas and Houthi forces in Yemen.