Donald Trump’s unilateral decision to withdraw some 2,000 American ground troops from Syria within 30 days struck Washington like a thunderbolt.

“We have defeated (Islamic State), my only reason for being (in Syria),” he said in a Twitter post on December 19, blithely disregarding the advice of his national security officials.

Trump’s abrupt announcement, though surprising, was not unexpected.

During the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, in a nod to his Republican base, he sharply questioned the wisdom of American intervention in Middle Eastern affairs. Promising a withdrawal, he claimed the United States had squandered trillions of dollars in engaging in wars in the Middle East.

Like his predecessor, Barack Obama, Trump believes that the United States is excessively embroiled in the Middle East and should devote fewer resources to it.

Nevertheless, Trump was persuaded to stay the course in Syria, having been convinced by his closest associates, including Secretary of Defence Jim Mattis, that a pullout would be foolhardy unless the Islamic State organization had been soundly defeated and as long as Iran was militarily entrenched in Syria, which has been convulsed by a civil war since 2011.

Last March, however, Trump declared, “We’ll be coming out of Syria, like, very soon.” And in a probable reference to Turkey, Western countries like France and Britain and Arab states such as Saudi Arabia and Egypt, he added, “Let the other people take care of it now.”

Trump, nonetheless, continued to support the key components of the U.S. mission in Syria — training, advising and supplying Kurdish and Sunni Arab fighters battling Islamic State, conducting air strikes against Islamic State, and keeping Iran in check.

Recognizing the importance of these objectives, top-level Trump administration officials let it be known that the United States had no intention of leaving Syria in the foreseeable future. The majority of U.S. forces were stationed in northeastern Syria, close to the Iraqi border.

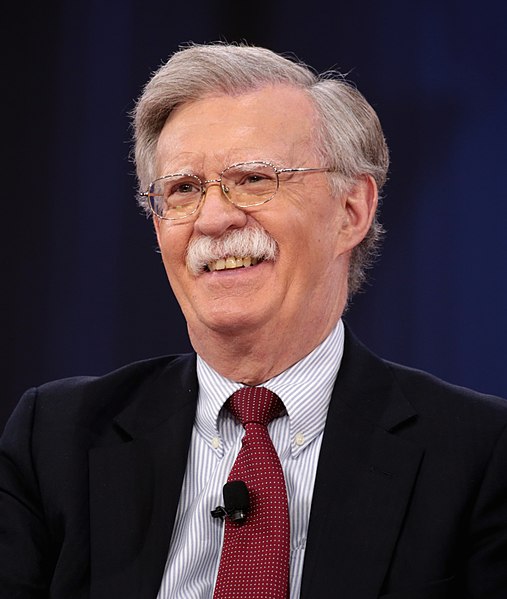

This past September, Trump’s national security adviser, John Bolton, said: “We’re not going to leave (Syria) as long as Iranian troops are outside Iranian borders and that includes Iranian proxies and militias.”

James Jeffrey, the U.S. representative charged with monitoring domestic affairs in Syria, said last week that the United States was “not in a hurry” to withdraw its forces from that country.

Earlier this month, Brett McGurk, the U.S. special envoy who monitors the war against Islamic State, warned the jihadists far from defeated, even though they have been driven from their strongholds in the Syrian city of Raqqa and Iraq’s second largest city, Mosul. “Nobody working on these issues day to day is complacent. Nobody is declaring a mission accomplished,” said McGurk, who resigned on December 22.

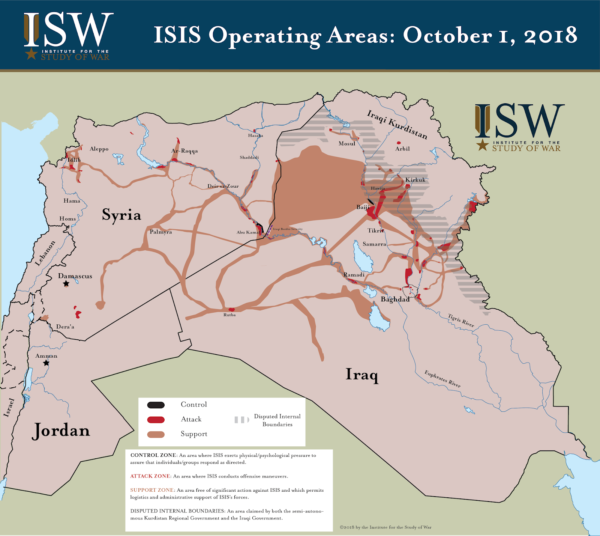

Last August, the Pentagon disclosed that Islamic State has almost 30,000 fighters in Syria and Iraq and is more capable than Al-Qaeda — Islamic State’s predecessor — was at its peak in 2006 -2007. Although Islamic State has lost virtually all the territory it controlled between 2014 to 2017, it is currently “waging an effective campaign to reestablish durable support zones, while raising funds and rebuilding command-and-control over its remnant forces,” says the Institute of the Study of War in Washington.

Islamic State could yet regain sufficient strength to mount a renewed insurgency in both Syria and Iraq, warns the institute.

Mattis, a former four-star Marine Corps general acutely aware of these looming dangers, tried to convince Trump that a premature withdrawal would be a “strategic blunder.” He urged Trump to maintain the status quo and keep U.S. troops and special forces in Syria to assist the Kurds, who have borne the brunt of the fighting against Islamic State.

He told Trump that a U.S. withdrawal would be regarded as a betrayal of the American-backed Syrian Democratic Forces, consisting mainly of Kurdish fighters. More to the point, he opposed the abandonment of critical territory in northeastern Syria to Russia and Iran, both of which back the Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

Rebuffed by Trump, Mattis resigned, but offered to remain at his post until February.

By all accounts, Trump decided to end the U.S. mission in Syria following a phone call with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who assured him that Turkey — a NATO member — could finish off what is left of Islamic State.

Turkey is deeply invested in Syria, having launched two major offensives into northern Syria against Kurdish fighters in the past two years — Operation Euphrates Shield in 2017 and Operation Olive Branch this year. The United States objected to both operations. Last week, the Pentagon warned Turkey that “any unilateral action in northeast Syria would be unacceptable.”

Now that Trump has ordered the withdrawal of U.S. forces in Syria, Turkey has a free hand to destroy an enclave the Kurds established south of the Turkish border. Turkey’s planned offensive is predicated on the assumption that the Trump administration will tolerate a third military operation.

It goes without saying that the imminent American withdrawal represents a victory for Russia and Iran, two of the United States’ fiercest adversaries and staunch allies of the governing Syrian regime, which is bound to be strengthened by the new U.S. policy.

Russia, Syria’s most important ally, has been asserting itself in the Middle East in the past several years. Trump’s withdrawal will only accelerate this process, giving Russian President Vladimir Putin the kind of influence and foothold in the region that his Soviet predecessors enjoyed from the 1950s to the 1980s. No wonder Putin applauded Trump’s decision.

Iran, Israel’s arch enemy, is also bound to reap tangible benefits from Trump’s lack of resolve. Which is precisely why Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu attempted to dissuade him from pulling out of Syria prematurely.

Israel fears that the U.S. withdrawal will enhance Iranian influence in Syria and embolden Iran to carry on with its project of building a land bridge from its territory to Syria and Lebanon. This corridor would be used to distribute advanced military equipment to Hezbollah and Shi’a militias based in Syria.

According to Israeli analysts, the U.S. presence in Syria was Israel’s only bargaining chip to persuade Russia to prevent Iran from deepening its entrenchment in Syria.

In response to the latest developments, Netanyahu pledged to redouble his efforts to combat Iran. “We will continue to aggressively act against Iran’s efforts to entrench in Syria,” he said the day after Trump’s announcement. “We do not plan to reduce our efforts. We will increase them. We will do this with the full support and backing from the United States.”

But since the Russians beefed up Syria’s air defences by installing the highly sophisticated S-300 anti-aircraft missile system, Israel has been forced to drastically reduce the number of air raids against Iranian military sites in Syria.

And now, with U.S. forces on the cusp of withdrawing from Syria, Israel may find it even more difficult to roll back the Iranian military presence there.