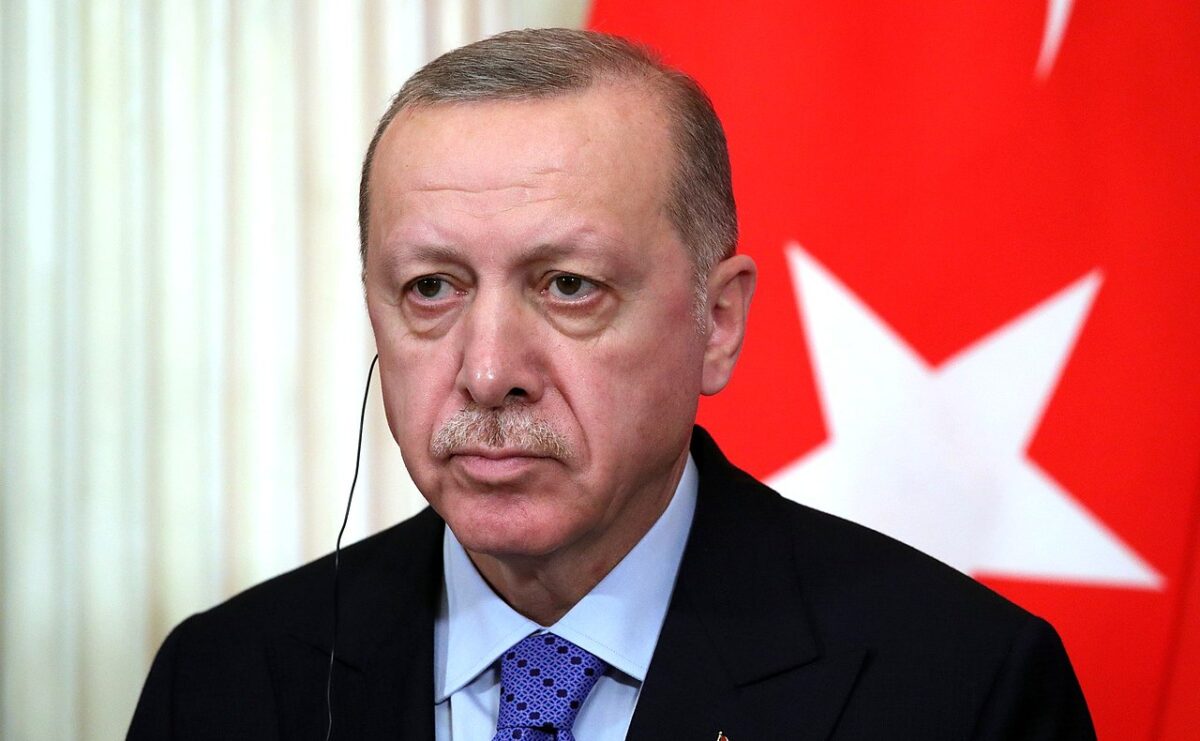

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan delivered a major policy speech on October 1 that confirmed yet again that Turkey under his administration is pursuing a neo-Ottoman foreign policy that blends Islamic consciousness with Turkish nationalism.

Harkening back to the era when the Ottoman Empire was a global hegemon and Palestine was one of its far-flung provinces, Erdogan implied that Jerusalem historically belongs to Turkey. Addressing parliamentarians in Ankara, he said, “In this city that we had to leave in tears during World War I, it is still possible to come across traces of the Ottoman resistance. So Jerusalem is our city …”

Jerusalem is one of Erdogan’s pet peeves. He has regularly condemned Israel’s efforts to “Judaize” it and lambasted the United States’ 2017 decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Most recently, he accused Israel of “constantly increasing its audacity in the holy sites in Jerusalem.”

Erdogan’s claim to Jerusalem may be absurd and laughable, but he meant every word of it. In recent years, Turkey — the first Muslim country to recognize Israel and the sole Muslim member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) — has pursued an increasingly assertive, even aggressive, foreign policy anchored by political, economic and military power.

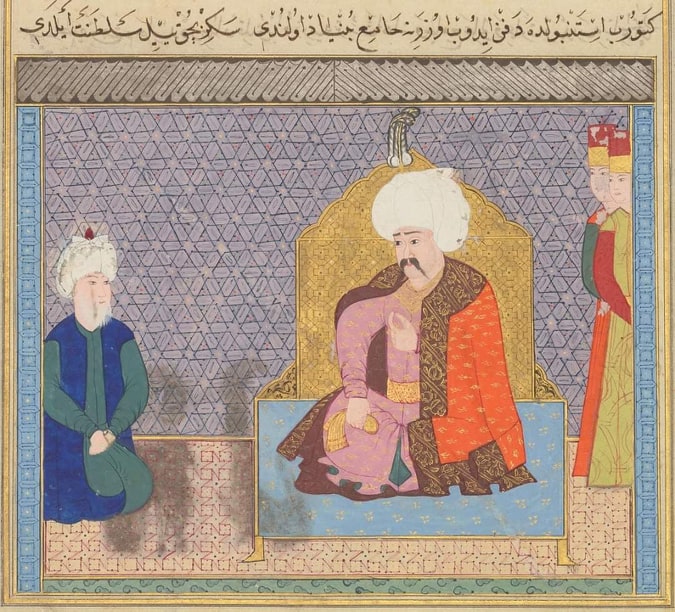

By all accounts, Erdogan models himself after Sultan Selim I (1512-1520), who seized territories in the Middle East and expanded the empire by 70 percent. In 2016, Erdogan dedicated a bridge over the Bosphorus named in his honor.

To some, Turkey’s promotion of a neo-Ottoman, pan-Islamist ideology is illustrated by its drift away from the West, its warm relations with the Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas and Qatar, its armed interventions in Syria, Libya and Iraq, its outspoken support for the Palestinian cause, and its financing of mosques and religious schools around the world.

Turkey’s assertiveness has somber implications for Middle Eastern and Mediterranean countries such as Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Greece and Cyprus. It is a reminder that Erdogan is fully committed to his neo-Ottoman project of projecting Turkish influence throughout the region.

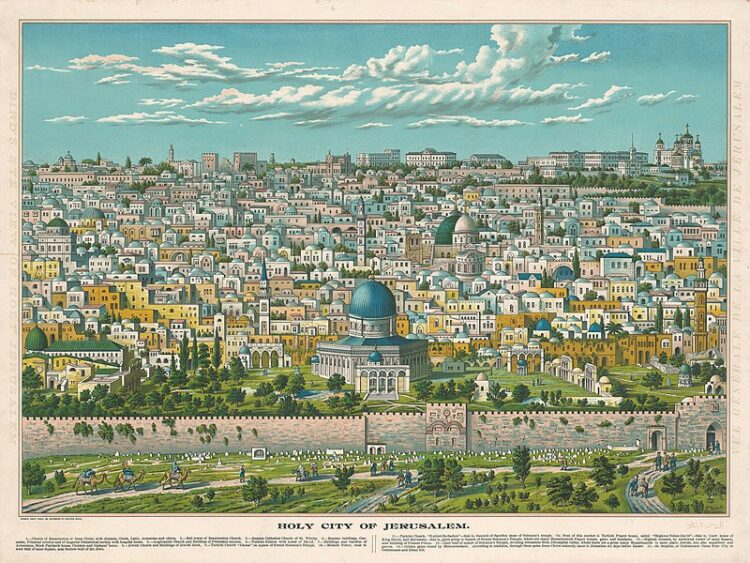

Before the 20th century, the mighty Ottoman Empire, populated by Muslims, Christians and Jews, stretched across the Middle East and extended into the Balkans.

The Ottomans conquered Palestine in 1517 and held it for four centuries until the British took control of it in 1917 after a series of decisive military campaigns. Today, 103 years after the humiliating Turkish retreat from Palestine, the architectural remains of the Ottoman Empire looms large in Israel and the eastern part of Jerusalem.

The incremental collapse of the Ottoman Empire unfolded under the impact of Greek, Bulgarian, Slavic and Arab secessionist movements and military defeats in the Balkans. Having been ousted from their colonial outposts, the Ottoman Turks were forced to relinquish vast swaths of land ranging from Eastern Thrace in Greece to northern Syria and Iraq.

With the establishment of a secular republic in 1923 under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Turkey abandoned Ottomanism as a viable political ideology. In short order, the Turks abolished the caliphate and the sultanate, replaced Arabic script with the Latin alphabet, and enacted a legal code inspired by European rather than Islamic principles.

Ottomanism remained effectively dead and buried until the Islamist-oriented, socially conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) won the 2002 general election. Erdogan, a former mayor of Istanbul and one of the founders of the AKP, was appointed prime minister in 2003 and president in 2014.

From 2009 onward, Turkey’s foreign minister was briefly Ahmet Davutoglu, an academic who had been Erdogan’s foreign policy advisor. Claiming that Turkey was destined to be a regional superpower, Davutoglu enunciated a doctrine of “zero problems with neighbors.”

Davutoglu’s policy was basically unrealistic because his boss, Erdogan, is a domineering politician who does not mince words and behaves like a bull in a china shop with respect to his relations with neighboring countries, particularly Israel.

Turkey and Israel formed close ties in the 1990s, following the 1993 Oslo peace agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization. But after Israel’s 2009 invasion of the Gaza Strip and the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident, during which Israeli commandos killed nine Turks aboard a Turkish ship trying to break Israel’s siege of Gaza, Turkey withdrew its ambassador in Tel Aviv and downgraded its bilateral relations with Israel.

Since then, Erdogan has denounced Israel on a regular basis and drawn closer to the Palestinians. This past August, Erdogan met Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in Istanbul. And last month, following Erdogan’s denunciation of Israel’s normalization agreement with the United Arab Emirates, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas phoned Erdogan to thank him for his support of the Palestinians.

Another source of tension between Israel and Turkey is the presence of the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA) in East Jerusalem. TIKA’s mission is to provide humanitarian assistance to Palestinians, but the Israeli government has accused it of attempting to undermine Israeli sovereignty in eastern Jerusalem.

In a caustic dig at Turkey’s effort to exert influence in East Jerusalem, Israel’s then foreign minister, Israel Katz, said, “The days of the Ottoman Empire are over.”

During a recent telephone interview with Arab journalists, Israeli Defence Minister Benny Gantz went one step further. He accused Turkey of attempting to undermine Israel’s normalization accords with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain and charged that Turkey is “supporting regional aggression.”

Erdogan’s assertion that natural gas discoveries within the Republic of Cyprus’ maritime zone must be shared with Turkey has caused problems as well. Turkey, having upgraded its naval force in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, has reportedly violated Greek airspace and intruded into its maritime zones.

Turkey’s assertiveness has resulted in closer links between Greece, Cyprus, Israel and Egypt in the fields of energy and security.

Turkey is also at loggerheads with Arab states.

Last month, Arab League foreign ministers denounced Turkey’s “interference in Arab affairs,” citing Turkey’s actions in Syria, Libya and Iraq. They also urged Turkey to “stop provocations that could erode trust and threaten the region’s security and stability.”

Egypt, having blasted Turkey’s backing of the now-banned Muslim Brotherhood, has spearheaded the campaign to build a united Arab front against Turkey.

At the Arab League meeting, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry described Turkey’s military interventions in Arab countries as the most significant emerging threat to Arab national security today.

Much to Turkey’s dismay as well, Saudi Arabia, one of its rivals in the Sunni Muslim camp, has started an undeclared economic boycott of Turkish goods.

The Saudis are especially incensed by Turkey’s alliance with Qatar, which is ruled by Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, and by its dispatch of several thousand troops to Qatar. Since 2017, Qatar has been subjected to a blockade by Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates.

Turkey has also established a military base in Somalia, its first Africa.

Saudi Arabia’s animosity toward Turkey could have grave consequences because the Arab market is important to Turkey’s economy, the world’s 16th largest.

Last year, Turkey exported $17 billion worth of goods to Arab countries, representing 19 percent of its exports. Arab states, in turn, exported $36 billion worth of products to Turkey. The biggest Arab buyers of Turkish goods are Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Turkey’s lucrative trade with the Arab world could be jeopardized by its neo-Otoman tilt. But Erdogan seems unconcerned. What matters most to him is projecting Turkish power and influence in the Middle East and beyond.