A month has passed since the July 15 failed coup in Turkey, and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has consolidated his power like never before.

Indeed, not since the days of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the father of the modern Turkish Republic, has any figure dominated the country for as long as Erdogan has.

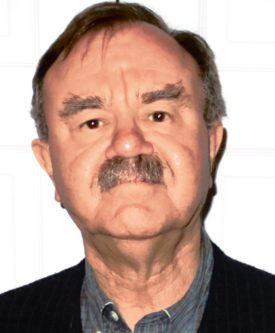

Fethullah Gulen, a cleric who has lived in the United States since 1999, is accused of being the mastermind behind the failed coup attempt. The ensuing purge of suspected “Gulenists” in Turkish society and government has seen some 82,000 people fired or suspended from their jobs as academics, judges, and military officials.

Even a national idol like Hakan Sukur, who in 2002 was part of the Turkish soccer team that made it all the way to the semi-finals of the World Cup, and was elected to parliament in 2011 on Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), has now gone into hiding, accused of being part of Gulen’s movement.

Sukur had voiced objections to government plans to shut down schools run by Gulen’s organization, Hizmet (“Service” in Turkish).

Angry at the lack of Western sympathy, and Washington’s continued unwillingness to extradite Gulen to Turkey, Erdogan is mending fences with a fellow autocrat. Russian President Vladimir Putin welcomed him in the Konstantin palace outside St. Petersburg on August 9.

Why the sudden turnabout? After all, Russia and Turkey were nearly at war with one another just a few months ago. In November, the Turks shot down a Russian jet that had entered their airspace from Syria, and the two countries are on diametrically opposite sides of the Syrian conflict.

Turkey has backed Syria’s opposition in its fight against Bashar al-Assad’s government in Damascus, while Russia is arguably its main defender.

Erdogan has decided that he wants less contact with the liberal democracies of Europe and America, according to journalist Anne Applebaum. After all, these are “states that believe in the legal norms which Erdogan wants to repress, states that might support the people Erdogan wants to lock up,” she noted in a Washington Post commentary.

The Russian president spoke at some length about restoring Russian-Turkish trade, resuming energy projects, lifting restrictions on tourism and reopening Russia’s construction sector to Turkish firms and workers.

Sanctions imposed by the Kremlin last autumn have hurt. Turkish exports to Russia dropped by 60 percent in the first half of the year.

Erdogan sees around him a web of conspiracies and threats, as he increasingly moves Turkey away from its secularist moorings and toward his own brand of Sunni Muslim nationalism. Indeed, many around him are convinced that the United States was itself involved in the attempt to remove him.

Minister of Justice Bekir Bozdag has said that Washington would be sacrificing its alliance with Ankara to a “terrorist” if it were to refuse to extradite Gulen. He told the state-run Anadolu Agency that anti-American sentiment in Turkey is reaching “its peak” over the issue and risks turning into hatred.

Bozdag’s remarks, which imply that Washington knew what was coming and did nothing, are being echoed by the pro-Erdogan Islamist media in Turkey, which sees the West as the enemy of Islam.

Kerem Oktem, a Turkish historian at the University of Graz in Austria, says that Erdogan sees his success in foiling the coup as “a narrative of an Islamist defense of democracy.”

The president is moving forward with his long-term project: the rejection of secular Kemalism in what he defines as the “New Turkey” – in actuality, a reversion to the glories of its Ottoman past as a Muslim empire.

Turkey also agreed to restore ties with Israel, with which it has been at odds since 2010. The failed putsch attempt by members of the Turkish military will serve to deepen Turkey’s newly restored ties with Israel.

Mutual security fears will act as a spur to reinforce the reconciliation agreement, Ilnur Cevik, a senior adviser to Erdogan, told Israeli news Channel 2 television.

“We feel Israel has always helped us in intelligence gathering. We need that in our fight against Daesh,” he said, calling the Islamic State by its Arabic acronym. “We need that in putting some order into Syria.”

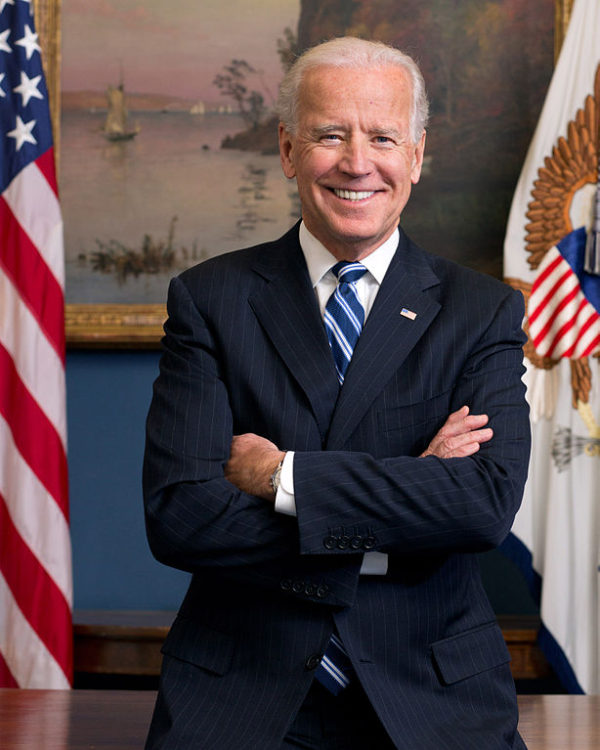

Meanwhile, U.S. Vice President Joe Biden will meet with Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan and Prime Minister Binali Yildirim during a visit to Turkey later this month, the first by a high-ranking American official since the failed coup.

Yildirim was quoted by Turkish media saying that Washington’s attitude had improved on an extradition request for Gulen.

Turkey’s democracy is still an experiment, still fragile and still at risk of a grave setback. Perhaps this will always be the case.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.