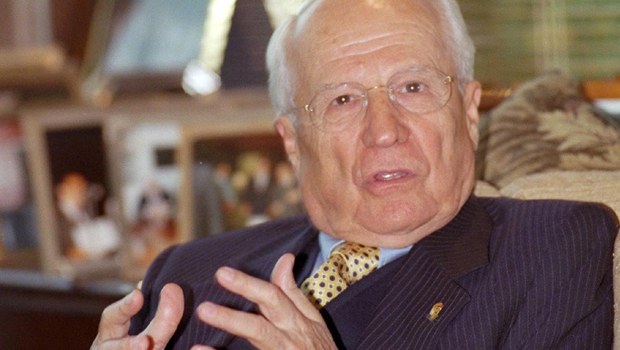

This past week we saw something unprecedented in Turkey: In a landmark decision meant to curb the power of the country’s massive military establishment, a court sentenced two top former generals, army chief Kenan Evren and air force head Tahsin Sahinkaya, to life imprisonment for leading a 1980 coup that resulted in widespread torture, arrests and deaths.

Evren, who then served as president of Turkey from 1980 to 1989, claimed the coup had saved Turkey from anarchy after thousands were killed in fighting between militant left-wingers and right-wingers.

Is the Republic of Turkey, the resolutely secular state founded in 1923 by Kemal Ataturk on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire, undergoing a fundamental transformation?

Ataturk reformed everything from dress codes to the alphabet during his 15-year reign as president. He even moved the country’s capital from Istanbul, the old imperial capital, to Ankara, in the heart of Anatolia.

And his legacy was guarded for decades afterwards by the Turkish Army. They carried out three coups between 1960 and 1980 and pushed an Islamist-led government led by Necmettin Erbakan from power in 1997. In 1998, his Welfare Party (RP) was banned.

But things have been changing. Since the 1990s, the revival of a Sunni-infused sense of nationalism is transforming the country.

The old republican verities have been challenged, especially by the current prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, himself a former member of the Welfare Party, who has been in office since 2003. He has now even taken on the generals, something earlier rulers did at their peril.

His popularity — he has won three elections in a row — has afforded him protection while he moved to break their power. His Justice and Development Party (AKP) holds a majority of the seats in parliament.

Erdogan, who was elected mayor of Istanbul in 1994, was himself arrested four years later, sentenced to 10 months in jail for “inciting religious hatred.”

He had publicly read an Islamic poem including the lines “The mosques are our barracks, the domes our helmets, the minarets our bayonets and the faithful our soldiers.” Because of his criminal record, he was barred from standing in elections or holding political office until 2001.

In another case, 230 army officers who were convicted in 2012 in the so-called “Sledgehammer” trial, accused of taking part in in an alleged plot to topple Erdogan, have been released.

Turkey’s Constitutional Court ruled that the officers’ rights had been violated in the handling of digital evidence and the refusal to hear testimony from two former top military commanders, as requested by defendants.

So the prime minister is not yet home free, though he himself recently began discrediting the convictions, because many of the prosecutors and investigators are followers of Fethullah Gulen, an Islamic preacher who lives in self-imposed exile in Pennsylvania. He was once Erdogan’s ally but now opposes him.

As well, could the country’s so-called “deep state” return? The term refers to a supposed clandestine network of military officers and their civilian allies who, for decades, suppressed and sometimes murdered anyone thought to pose a threat to the secular order.

Human rights groups accused them of thousands of political deaths and disappearances during the 1990s.

It’s no secret Erdogan plans to run for president this coming August, when Turkey’s head of state will be directly elected by the people, for the first time ever.

Will there now be genuine civilian oversight when it comes to the armed forces? Has Erdogan actually managed to tame the Turkish military, or will he meet the fate of earlier civilian rulers unseated by coups? Right now, he does seem to have the upper hand.

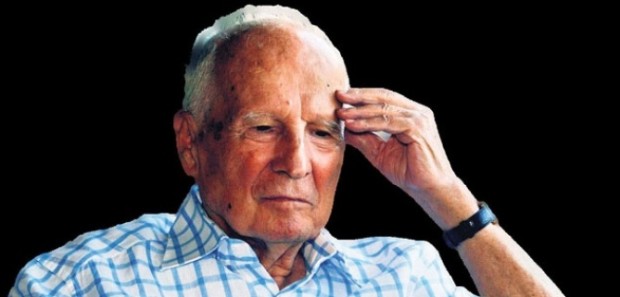

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.