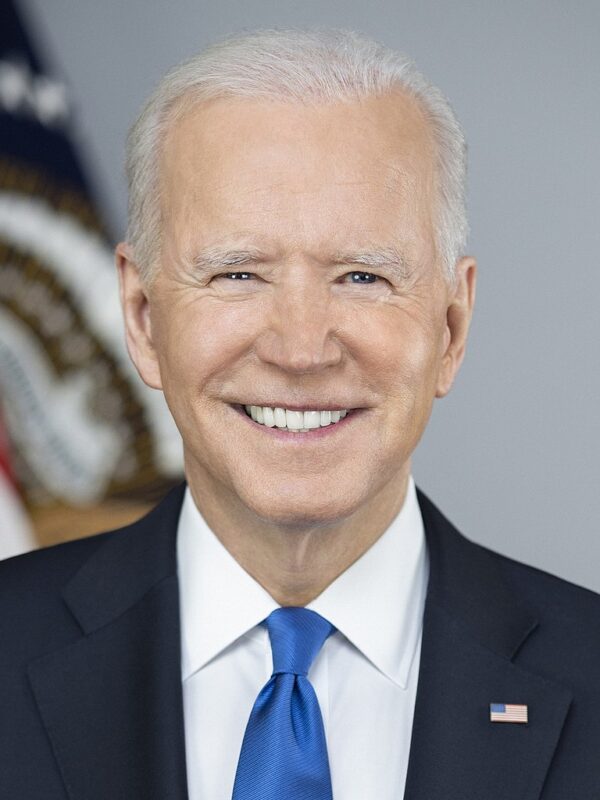

A little more than two months after succeeding Benjamin Netanyahu as prime minister, Naftali Bennett will have his first opportunity to meet U.S. President Joe Biden. They will confer at the White House on August 26.

Biden’s press secretary, Jen Psaki, said the visit would “strengthen the enduring partnership between the United States and Israel, reflect the deep ties between our governments and our people, and underscore the United States’ unwavering commitment to Israel’s security.”

“The president and … Bennett will discuss critical issues related to regional and global security, including Iran,” she noted.

In the main, they will exchange views on two key issues — Iran and the Palestinians. However, Bennett will also attempt to improve Israel’s somewhat dented relations with Biden’s Democratic Party, which frayed during Netanyahu’s divisive premiership, and to establish a solid relationship with Biden.

Like Netanyahu, Bennett opposes a U.S. return to the original Iran nuclear agreement, which Israel lambasted and from which Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump, withdrew unilaterally in 2018.

The Biden administration seeks to strengthen and lengthen the 2015 accord by adding new provisions to it intended to curb Iran’s aggressive foreign policy in the Middle East, its support of anti-Israel surrogates like Hezbollah and Hamas, and its ballistic missile program.

As well, the United States hopes to prolong the longevity of the agreement to prevent Iran from reconstituting its nuclear program after the expiry of the deal in about four or five years from now. Under the accord, Iran agreed to freeze it in exchange for sanctions relief.

For the past few months, the United States and the other signatories of the agreement — Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany — have engaged Iran in talks in Vienna in the hope of reviving it and expanding its scope.

No major breakthroughs have occurred, and it is highly questionable whether Iran will accept the changes demanded by the United States, especially now that a conservative hardliner, Ebrahim Raisi, has been elected as Iran’s new president succeeding Hassan Rouhani.

Bennett, in his talks with Biden, will try to work out a joint strategy regardless of whether the negotiations in Vienna succeed or fail.

Primarily, Bennett will try to dissuade Biden from reentering the deal and present him with “an orderly plan that we have formulated in the past two months to curb the Iranians, both in the nuclear sphere and vis-à-vis regional aggression.”

The agreement is “no longer relevant, even by the standards of those who once thought that it was,” Bennett claimed on August 22.

Israel may wish to restore its military option to ensure that Iran does not attain a military-grade nuclear capability. Netanyahu, particularly from 2010 to 2012, threatened to bomb Iranian nuclear sites.

It’s clear why Netanyahu walked away from this drastic course of action. A preemptive Israeli strike will likely trigger a regional war with Iran and its Lebanese Shi’a ally, Hezbollah, and expose Israel to massive missile attacks that would most probably cause a frightening number of deaths and injuries and enormous property damage.

Bennett and Biden will also discuss the Palestinian political question, which has been simmering since the breakdown of bilateral talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority in the spring of 2014.

Netanyahu made no genuine attempt to resuscitate these negotiations, nor did he maintain even the slightest semblance of person-to-person contact with the president of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas.

Indeed, Netanyahu sidelined Abbas, denigrating him as an unreliable and untrustworthy partner. And most importantly, he distanced himself from a two-state solution after grudgingly embracing it in 2009 following his reelection as premier.

Ideologically, Bennett stands to the right of Netanyahu, vehemently opposing Palestinian statehood but supporting autonomy for the Palestinians. Bennett, too, has called for the annexation of Area C, which comprises nearly two-thirds of the West Bank, where a future Palestinian state would be located.

In addition, Bennett is an avid supporter of the settlement movement beyond the pre-1967 Green Line. Earlier this month, his cabinet approved a plan to build several thousand new housing units in Israeli settlements, while green lighting the construction of about 1,000 Palestinian homes in Area C.

The U.S. State Department criticized Israel’s proposal. “We believe it is critical for Israel and the Palestinian Authority to refrain from unilateral steps that exacerbate tensions and fundamentally undercut efforts to advance a negotiated two-state solution,” a U.S. spokesman said. “This certainly includes settlement activity.”

In his last meeting with Netanyahu in May, following the brief cross-border war in the Gaza Strip, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken reiterated Washington’s firm support for a two-state solution.

As he put it, “We continue to believe very strongly that (it) is not just the best way, but probably the only way to really assure that going forward Israel has a future as a secure Jewish and democratic state, and the Palestinians have a state to which they’re entitled.”

In a bid to improve Israel’s relations with the United States, Bennett is prepared to make some cosmetic goodwill concessions to the Palestinians.

These would range from strengthening the Palestinian Authority and increasing the number of work permits given to Palestinians to expanding the list of imports Israel allows into the West Bank and decreasing the frequency of raids the Israeli army conducts in Area A, which is theoretically under full Palestinian control.

Bennett, in his discussions with Biden, will try to mend fences with the Democratic Party and restore Israel’s bipartisan image. Netanyahu’s relations with the Democrats took a nose dive during Trump’s presidency, which conferred benefits on Israel, ranging from the U.S. recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital to the American recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the disputed Golan Heights.

In his first major speech in office, Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid promised to repair Israel’s ties with the United States, its chief ally and benefactor.

“The outgoing government took a terrible gamble, reckless and dangerous, to focus exclusively on the Republican Party and abandon Israel’s bipartisan standing,” said Lapid in mid-June. “We find ourselves with a Democratic White House, Senate and House, and they are angry. We need to change the way we work with them.”

Lapid, in his first official meeting with Blinken in June, discussed that issue. “In the past few years, mistakes were made,” he said. “Israel’s bipartisan standing was hurt. We will fix those mistakes together.”

Israel’s relations with the Democrats may get better in the months ahead, given Biden’s consistent pro-Israel record during his years as vice-president and a U.S. senator. But if Israel and the United States cannot formulate a common approach to Iran, and if the Israeli government expands settlements in the West Bank, tensions will surely flare.

Certainly, a handful of progressive Democrats in the House of Representatives will continue to be critical of Israel’s policies concerning the Palestinians. They include Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, Rashida Tlaib of Michigan and Cori Bush of Missouri.

These four women, two of whom are Muslims, symbolize the changing demographics of a country that is becoming increasingly diverse and non-white from an ethnic and racial point of view.

The incremental transformation of the American population could have an impact on U.S. policy toward Israel in the future.