The United States and Iran are enemies yet partners in the fast-changing political landscape of the Middle East.

As the old saying goes, politics makes for strange bedfellows.

Once Iran’s close ally, Washington severed diplomatic relations with Tehran in 1979 after its embassy in Iran was seized by an Iranian mob. Since that momentous moment, the two countries have been adversaries.

But with Islamic State having emerged as a clear and present danger to the established order in the Middle East, the United States and Iran have temporarily set aside their seemingly irreconcilable differences so as to confront that rampaging Sunni jihadist organization.

While both nations share a common interest in eradicating Islamic State’s presence in Iraq and Syria, they’re at odds even there.

In Syria, Iran fervently supports the Baathist regime of President Bashar al-Assad, who’s struggling for survival in a civil war that has entered its fifth year. The United States, on the other hand, has called for regime change in Damascus while backing Syrian forces opposed to Assad’s dictatorial rule.

Despite its implacably hostile attitude to Assad, the United States is implicitly propping him up by bombing Islamic State sites in Syria. Islamic State, Assad’s most serious enemy, has conquered extensive swaths of territory in Syria since 2013.

Without U.S. air strikes, Islamic State might already have gobbled up yet more Syrian land and even toppled Assad by now. Facing this looming prospect, Washington chose to assist Assad, the lesser of the two evils. Assad, after all, is a nationalist opposed to the brand of Islamic radicalism espoused by Islamic State.

Iran, a foe of Sunni jihadism as well, had no problem backing Assad. Lest it be forgotten, Iran and Syria have been aligned since the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War in 1980. Nonetheless, Iran’s strategic alliance with Syria seems strange, at least on the surface. Iran is an Islamic theocracy, while Syria is staunchly secular.

What binds them together, oddly enough, is religion. Iran, the preeminent Shiite power in the Middle East, has a natural affinity with Assad because he’s a member of the minority Alawite sect, a breakaway group from mainstream Shiite Islam.

Given its vested interest in preserving the Assad clique, Iran has provided Assad with massive levels of political and military support since the eruption of the civil war in Syria, which has claimed the lives of more than 230,000 civilians and soldiers.

In Iraq, a majority Shiite state controlled by Sunni Arabs until the fall of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime in 2003, the United States and Iran share an identical objective — breaking Islamic State’s occupation of areas in northern and western Iraq. Last June, Islamic State captured Mosul and Tikrit, among other cities and towns in Iraq. Earlier this month, the Iraqi government launched a spring offensive to retake this territory.

About a year ago, William Burns, the then U.S. deputy secretary of state, conferred with Iranian diplomats to explore the feasability of a joint effort to defeat Islamic State in Iraq. Even as these talks took place, Iran’s anti-American supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, denounced the notion of American intervention in Iraq.

Khamenei’s denunciation was really beside the point.

The United States officially withdrew its troops from Iraq four years ago, but its sway in Baghdad remains considerable. The United States has bombed Islamic State targets in Iraq since last summer, sold advanced military equipment to Iraq, trained Iraqi soldiers and sent some 3,000 military advisors to Iraq.

Iran is deeply invested in Iraq, too.

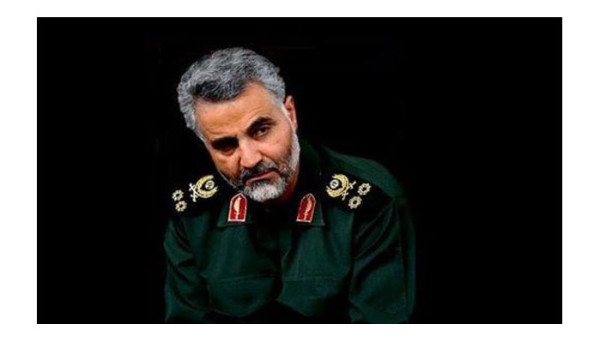

Under the direction of General Qassim Suleimani, the commander of the elite Quds Force, Iran has trained and armed Shiite militias, which once attacked U.S. soldiers in Iraq. The Iranian air force has also bombed Islamic State bases in Iraq.

In a tangible sign of their implicit cooperation in Iraq, U.S. jets recently pounded Tikrit, hitting Islamic State staging areas, checkpoints, buildings and bridges. These raids enabled the Iraqi army and Iranian-backed militias to recapture Tikrit, Saddam Hussein’s hometown. Iran’s decision to help Iraq is bound to increase Tehran’s clout in a country that was firmly in the American camp from 2003 to 2011.

Overlapping interests in Iraq and Syria bring the United States and Iran closer together, but elsewhere in the Middle East, they’re poles apart.

Washington is Israel’s most important friend and benefactor, but to Iran — an avid supporter of the Palestinian cause — Israel is an illegitimate entity worthy of destruction. Iran has been an ardent patron of Hamas and Hezbollah, both of which have gone to war with Israel in recent years.

In Yemen, which has tumbled into anarchy since the Arab Spring rebellions of 2011 and 2012, the United States and Iran are at loggerheads.

Iran backs the Houthis, a Shiite group that has seized the capital, Sana, and currently besieges the port of Aden. The United States and Yemen’s neighbor, Saudi Arabia, support the country’s president, Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who was ousted by the Houthis and driven into exile.

During the third week of April, a U.S. aircraft carrier flotilla, spearheaded by the Theodore Roosevelt, forced an Iranian convoy suspected of carrying weapons for the Houthis to turn back. The U.S. defence secretary, Ashton Carter, had warned Iran not to “fan the flames” of the conflict that has enveloped Yemen.

Iran’s growing influence in the region — particularly in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon and Yemen — has alarmed Israel and Sunni states like Saudi Arabia and Jordan. What adds to their fears is the assumption that Iran will become bolder and more assertive in the region once a nuclear agreement is signed.

U.S. President Barack Obama has promised Saudi Arabia’s new monarch, King Salman, that a nuclear accord “will not in any way lessen United States concern about Iran’s destabilizing activities in the region.” John Kerry, the U.S. secretary of state, has gone further. “We are not seeking a grand bargain,” he said, having assured Saudi Arabia that the Obama administration does not seek a rapprochement with Iran at the expense of its Arab rivals, much less Israel.

Kerry’s reference to a “grand bargain” is larded with historic overtones.

In May 2003, shortly after the United States invaded Iraq, Iran offered Washington a deal. In exchange for restoring diplomatic relations, ending economic sanctions and recognizing Iran’s security interests in the Middle East, Iran promised to accept the 2002 Arab League peace proposal, provided Israel withdrew to the pre-1967 armistice lines. Iran also pledged to end material support to Palestinian radical factions like Hamas and Islamic Jihad and to bring pressure on them “to stop violent actions against civilians within Israel’s 1967 borders.”

U.S. President George W. Bush rejected the Iranian offer.

Twelve years on, in keeping with Obama’s outreach effort to the Iranian government since his inauguration in 2009, the United States is trying to improve relations with Iran.

Even if a nuclear agreement is signed, it’s doubtful whether Washington can resurrect the golden era of bilateral relations with Iran that prevailed during the pre-revolutionary Pahlavi period. But if the United States manages to normalize ties with Iran after more than three decades of mutual hostility and estrangement, the Middle East will be hugely affected by this seminal development.