With a United Nations arms embargo against Iran expiring on October 18, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has let it be known that the United States will “exercise all diplomatic options” to extend it indefinitely.

It’s doubtful whether the United States will succeed in depriving Iran of new weapons. Two major powers oppose Washington’s policy, and they have the power to stymie it. Nonetheless, the U.S. is proceeded with its campaign.

The UN banned Iran from purchasing weapons in 2010, thereby preventing the Iranian regime from replacing its aging military equipment, much of which was bought from the United States before the 1979 Islamic revolution.

The ban was extended for five years in 2015 when Iran and six majors powers — the United States, Russia, China, France, Britain and Germany — signed an agreement to freeze Iran’s nuclear program for at least 15 years in exchange for relief from an economic embargo.

Two of Iran’s chief allies, China and Russia, were less than keen to extend the arms embargo, but reluctantly agreed to it so that the nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, could be sealed.

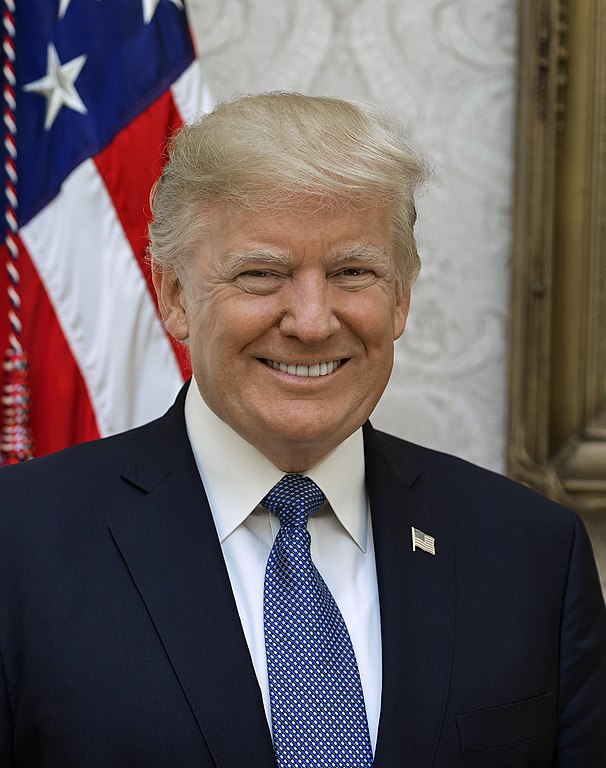

In 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew from the accord, claiming it was one of the worst deals in modern history. He argued that Iran’s nuclear program had not been shut down completely and that Iran was sowing instability in the Middle East.

Trump also imposed severe economic sanctions on Iran and launched a campaign of “maximum pressure” against the Iranian government in the hope that Iran’s leadership, headed by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, would agree to revamp the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action to his satisfaction.

Reacting to these punitive measures, Iran began violating the agreement by enriching uranium to higher levels, thereby heightening tensions with the United States.

With a little more than two months to go before the UN arms embargo expires, the Trump administration is mulling the possibility of introducing a Security Council resolution to extend it.

Washington’s chances of success are non-existent because Russia and China, two of the Security Council’s permanent members, would veto such a resolution. Meanwhile, three key U.S. allies — Britain, France and Germany — have expressed unease over the Trump administration’s aggressive approach to Iran.

Assuming that Russia and China block a U.S. resolution, the United States is likely invoke the “snapback” provision in the nuclear agreement to reimpose UN sanctions on Iran.

The Trump administration’s policy is rooted in a statement made by President Barack Obama five years ago. “If Iran violates the agreement over the next decade, all of the sanctions can snap back into place,” he said. “We won’t need the support of other members of the UN Security Council.”

Easier said than done.

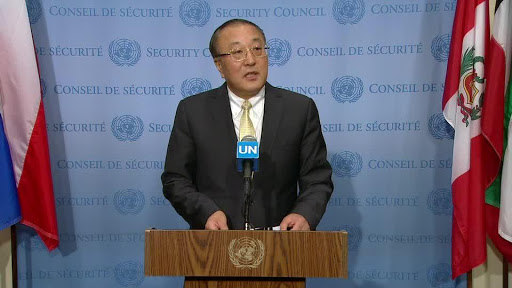

China, which recently signed a 25-year economic and security partnership with Iran, sharply disagrees with the U.S. rationale. As its ambassador to the UN, Zhang Jun, said recently, “Having quit the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the U.S. is no longer a participant and has no right to trigger a snapback.”

Russia’s ambassador, Vassily Nebenzia, has dismissed as “ridiculous” Washington’s ploy to employ the snapback provision. Having pulled out of the nuclear pact, the United States cannot use the UN to inflict further economic pain on Iran, he said.

Germany’s envoy, Christoph Heusgen, acknowledges that Iran is a disruptive force in the region, but also agrees with the Chinese and Russian position that the United States cannot compel the UN to slap new sanctions on Iran, whose oil-based economy has been crippled by American sanctions.

Israel, Iran’s arch enemy, has called on the UN implement snapback sanctions on Iran in response to its “repeated provocations and violations.”

“I don’t think we can afford to wait,” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu told Trump’s special representative for Iran, Brian Hook, during his visit to Israel in June. “We should not wait for Iran to start its breakout to a nuclear weapon because when that happens it will be too late for sanctions.”

Hook argues that the embargo must remain in place to stop Iran from becoming “the arms dealer of choice for rogue regimes and terrorist organizations around the world.”

“If you let (the embargo) expire,” he added, “you can be certain that what Iran has been doing in the dark, it will do in broad daylight and then some.”

Iran has provided arms to two of Israel’s enemies — Hezbollah and Hamas — and to its allies in Iraq and Yemen. Last winter, a U.S. naval vessel intercepted a ship attempting to smuggle Iranian weapons to Houthi rebels in Yemen, finding on board 150 anti-tank guided missiles, three surface-to-surface missiles and component parts for unmanned explosive boats.

“Iranian weapons already put American and allied troops in the region under threat and endanger Israel,” Hook wrote in a Wall Street Journal piece in May. “Letting the embargo expire would make it considerably easier for Iran to ship weapons to its allies in Syria, Hamas in Gaza and Shiite militias in Iraq.”

As Hook pointed out, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani looks forward to the day when the embargo ends. “When it is lifted, we can easily buy and sell weapons,” Rouhani said last year.

By all accounts, Iran plans to upgrade its air force and army with such Russian weapons as the SU-30 fighter jet and the T-90 tank. Iran would also try to buy Russia’s S-400 anti-aircraft missile system and its Bastian coastal defence system.

Russia, one of the leading arms exporters, has made no secret of its desire to resume sales to Iran.

China, which has upgraded its military cooperation with Iran and participated in Iranian military exercises, would be eager to sell weapons to Tehran as well.