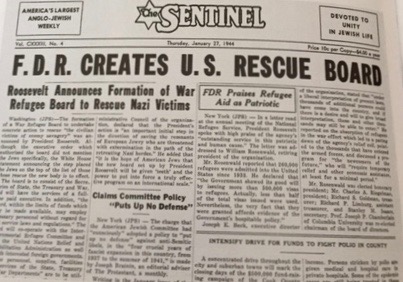

Amid the horrors of the Holocaust, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt created the War Refugee Board in 1944 to rescue European Jews imperilled by the genocidal policies of Nazi Germany and like-minded allies like Hungary, Slovakia and Romania. Although it was established long after millions of Jews already had been murdered in mass shootings and in extermination camps, and although it functioned for only 20 months, it still managed to save countless lives.

Rebecca Erbelding, an American scholar, has written a definitive account of its formation and contributions. Rescue Board: The Untold Story of America’s Efforts to Save the Jews of Europe (Doubleday) is thorough in every respect, though its title leaves the misleading impression that it is the first work of its kind. That being said, Erbelding — an archivist, curator and historian at the United States Holocaust Memorial museum in Washington, D.C. — has produced what is probably the most comprehensive book about this important but often overlooked topic.

As she suggests, the creation of the War Refugee Board was something of a miracle. American political and military leaders generally believed that the United States could only truly help Jews trapped in Nazi-occupied countries by winning World War II as soon as soon as possible. In their view, everything else, including rescue efforts, was “a distraction and a diversion of resources,” she says.

Erbelding adds that a historically high level of public antisemitism and restrictive immigration laws that targeted Jews, among others, worked against the formation of a U.S. government body to assist endangered European Jews. Ninety four percent of Americans disapproved of the Nazi persecution of Jews, particularly after Kristallnacht, according to a Gallup poll. But this sentiment did not translate into “a public appetite” for increasing immigration quotas.

In 1939, as she points out, Senator Robert Reynolds of North Carolina, an isolationist, racist and admirer of Germany, introduced five bills in the Senate proposing cutting quotas by 90 percent. Reynolds’ bills died on the Senate floor, but just a few months later the United States turned away the St. Louis, a German passenger ship carrying 937 mostly Jewish passengers.

Washington did admit 100,131 Jewish refugees under the German quota from 1938 to 1940. But with Fifth Column hysteria rampant among many Americans, the United States subsequently tightened procedures for screening refugees. As a result, immigration from Nazi-occupied and collaborationist nations dropped by 38 percent between 1940 and 1941.

Against this backdrop of deepening suspicion of new immigrants, the U.S. vice-consul in Geneva, Howard Elting, received a visit from Gerhard Riegner, the representative of the World Jewish Congress in Switzerland, in early August 1942, eight months after the United States had entered the war.

Riegner had heard indirectly from a prominent German industrialist that the Nazis intended to murder the Jews of Europe and thereby solve the “Jewish question in Europe.” Elting believed Riegner, who asked that his message be transmitted to Rabbi Stephen Wise, the head of the World Jewish Congress, through the U.S. State Department.

Officials at the State Department’s European desk were skeptical, even dismissive, of Riegner’s information. But it reached Wise by the end of August thanks to a British parliamentarian. It took the State Department about a month to look into the matter, but in the meantime, Wise and four other rabbis were granted an appointment with Roosevelt at the White House. During their meeting, they presented the president with a petition asking him to warn Germany to desist from antisemitic atrocities and to appoint a special commission to investigate Nazi crimes.

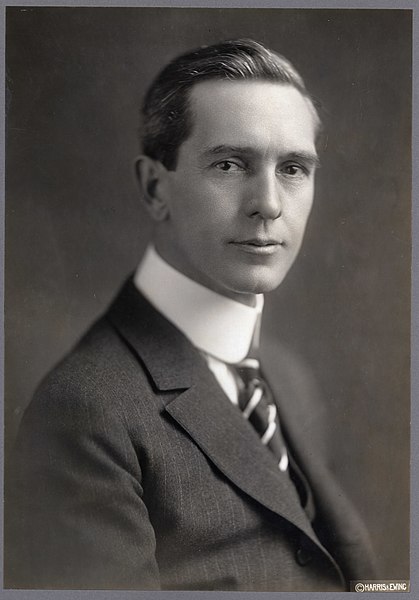

Roosevelt was open to their concerns, but a group of State Department functionaries in the European and Visa divisions claimed that only an allied military victory over Germany could stop the Nazis from killing Jews en masse. Two of these officials were Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long and a member of his staff, R. Borden Reams, who had urged Wise to cancel, or at least tone down, his campaign about the Nazi mass murder of Jews.

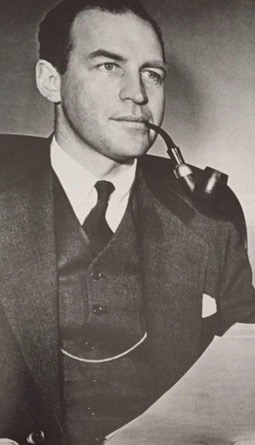

It was at this critical point that John Pehle, a 31-year-old Treasury Department official, appeared in the picture. He was in charge of the Foreign Funds Control bureau, whose mandate was to keep billions of dollars out of the hands of America’s enemies and supervise the flow of relief funds from the United States into Europe. Unlike some other bureaucrats, he thought that the United States should be of assistance to European Jews even as the war raged.

Toward the close of 1943, when the majority of Jews in Poland already had been killed, Rabbi Eliezer Silver, the president of the Union of Orthodox Jews, and a delegation of rabbis arrived in Washington to plead for the establishment of an agency to rescue Jews in Europe.

Erbelding says the idea had first been raised by Peter Bergson, a young Palestinian Jew. The Senate Foreign Affairs Committee was receptive, as was Sol Bloom, who headed the House Committee on Foreign Affairs.

Around this time, Pehle decided to use his powers to streamline aid to Jews in France and Shanghai, China, and present arguments why the United States must do more to assist Jews. On January 13, 1944, Pehle and his colleagues handed Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. a report saying that the U.S. would have to share responsibility for the Nazi extermination of Jews if it did not take immediate action. Morgenthau told Roosevelt that his administration was, in effect, “aiding and abetting Hitler” by virtue of the fact that State Department officials like Long had obstructed rescue efforts.

Roosevelt, needing no convincing, announced the formation of the War Refugee Board. He said it would develop plans for the rescue, maintenance, transportation and relief of the victims of Nazism and, if possible, oversee safe havens for refugees who had escaped Nazi occupation.

“The twenty months between the board’s creation in January 1944 to its closure in September 1945 represent a moment in history when American action matched American rhetoric about democratic values,” says Erbelding.

In short order, Long was removed from immigration and refugee matters and assigned to congressional relations, and was replaced by Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle. Pehle was appointed acting director of the War Refugee Board, the senior staff of which consisted largely of the children of immigrants.

Pehle’s task was daunting, Erbelding notes. “Pehle was determined to use the tools of bureaucracy — administration, government communications and official diplomacy — to speed rescue … Time, distance, the war and the limits of imagination all conspired against him. Europe was in perpetual darkness. The staff of the War Refugee Board never had a clear picture of the true situation in (Nazi) occupied lands.”

Nevertheless, Pehle laid out a two-pronged strategy: persuade Nazis and Nazi collaborators to stop the killing, and try to rescue those who could still be saved.

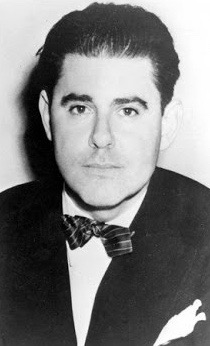

The board’s first overseas representative, Ira Hirschmann, a vice-president of a major New York City department store, was dispatched to Turkey, a neutral country, to ascertain whether he could facilitate the transit of Jewish refugees to Palestine, a British mandate. He arrived in Ankara in February, shortly after the Struma, a rickety ship packed with 781 refugees, was sunk in the Black Sea by a Soviet submarine.

Hirschmann met a Romanian diplomat to discuss the fate of 50,000 Bukovinian and Bessarabian Jews stranded in Transnistria, a region in Ukraine between the Bug and Dniester rivers under the control of Romania, a German ally. Hirschmann demanded that their safety should be guaranteed, and the Romanians complied. A short while later, he was involved in a fruitless ransom scheme, hatched by the Nazis, to barter Hungarian Jews for military vehicles and consumer goods.

In May, two months after Germany invaded Hungary, its ally, Pehle learned that the deportation of Hungarian Jews had begun. Within a span of 56 days from May 15 to July 9, some 437,000 Jews were sent to Auschwitz, most to their immediate deaths. In a bid to save Hungary’s remaining 200,000 Jews, concentrated in Budapest, Pehle came up with the idea of using protective papers to save them.

At Pehle’s urging, Sweden agreed to post a Swedish businessman, Raoul Wallenberg, to its embassy in Budapest. He arrived after Miklos Horthy, the Hungarian supreme leader, had ordered an end to the mass deportations of Jews. However, Jews were still being persecuted, rounded up and interned. Amid this reign of terror, Wallenberg saved many lives.

As Wallenberg issued a flood of protective papers, the United States offered to take Jews if Hungary would release them to its custody. Among them were Vilmos and Jolie Gabor, one of whose daughters, Sari, was already living in Hollywood under the stage name of Zsa Zsa Gabor.

Strangely enough, Pehle did not endorse a plan, submitted by the Union of Orthodox Rabbis, to bomb the rail lines from Hungary to Auschwitz, doubting whether a bombing campaign would do any good. In any event, the U.S. secretary of war, John McCloy, vetoed the suggestion on the grounds that it would be “impracticable.” In his opinion, “the positive solution to this problem is the earliest possible victory over Germany, to which end we should exert our entire means.”

The War Refugee Board also played a role in alleviating the agony of Jews in Slovakia. Allied with Germany under the leadership of the Catholic priest Jozef Tiso, Slovakia was the first unoccupied country to voluntarily deport its Jewish citizens, 57,000 in total, to Nazi death camps in Poland in 1942. With 24,000 Slovakian still at the mercy of Tiso’s fascist regime, Pehle called upon Switzerland, Sweden, the International Red Cross and the Vatican to send strong warnings to Slovakia to end the deportations.

The board’s final major project was to send food, clothing, soap and medical packages to German concentration camps, notably Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen. It proved to be one of the largest bureaucratic and logistical challenges.

Pehle resigned as director on January 27, 1945, the day the Red Army liberated Auschwitz, and opened a law firm in Washington specializing in international commercial law. His replacement, William O’Dwyer, stayed briefly, entering the mayoralty race in New York City.

Pehle rarely discussed his work at the board, nor did he keep a diary. But in a letter to his college English professor, Father Francis Reilly, he wrote, “I consider myself fortunate to have been asked to serve our government in conducting an emergency program of relief and rescue of the persecuted minorities of Europe. It has been a rewarding experience. It has given me a chance to reduce a shocking injustice if only by a minute amount. I wish I could do more.”

In closing, Erbelding observes that the creation of the War Refugee Board was the only instance in American history when the United States “founded a government agency to save the lives of non-Americans being murdered by a wartime enemy.” Its establishment was an anomaly, a surprising “altruistic moment” in a country rife with racism and antisemitism that, until then, had made only half-hearted attempts to help persecuted European Jews.

The number of Jews saved by the War Refugee Board can never be known, says Erbelding. “So much of (its) work was intangible. It shot arrows into the dark, hoping to have an impact but rarely knowing if a particular project succeeded.”

But one of its highly-placed officials, Paul McCormack, cited a figure of 126,604 persons rescued. Another official, Florence Hodel, wrote, “The accomplishments of the board cannot be evaluated in terms of exact statistics, but it is clear that hundreds of thousands of persons, as well as tens of thousands who were rescued through activities organized by the board, continued to live and resist as a result of its vigorous and unremitting efforts, until the might of the Allied armies finally saved them and the millions of others who survived the Nazi holocaust.”

Concurring with this appraisal, Erbelding writes, “The War Refugee Board tried everything in its power to prevent atrocities, provide relief and rescue potential victims. The staff worked ceaselessly to save lives during the final months of the Holocaust.”