The United States is torn by indecision in Syria, and recent events illustrate this pattern of confusion.

On April 7, Syrian government forces launched a chemical attack in Douma, a suburb of Damascus, and it immediately placed the United States on the horns of a dilemma. President Donald Trump was reluctant to intervene, in line with his America First policy of disentangling the United States from extremely costly Middle East wars. Yet Trump had vowed to punish Syria for deploying prohibited non-conventional weapons of mass destruction.

Taking to Twitter, he wrote, “Many dead, including women and children, in mindless CHEMICAL attack in Syria. Big price to pay.” He blamed Russia and Iran for supporting the Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad and Russia, in particular, for failing to abide by a 2013 agreement to secure and destroy Syrian chemical weapons.

After mulling the matter for almost a week, Trump adopted an aggressive approach. On April 13, the United States, Britain and France bombed three chemical weapons facilities in Syria, hitting them with a barrage of missiles and bombs fired from ships and aircraft.

It was not the first time Trump had resorted to military means to punish Syria. Last April, following a Syrian chemical assault that caused the deaths of about 100 civilians in the rebel-held town of Khan Sheikhoun, the United States struck an airfield in Syria, destroying 20 combat planes and killing nine Syrian soldiers.

This shock-and-awe strike, while exacting a price from Assad, did not in the least change the status quo on the ground in Syria, a free-for-all arena for external powers to expand their influence in the Middle East.

Earlier, on March 29, Trump disclosed that the United States would withdraw its 2,000 troops, plus a few thousand U.S. contractors, from Syria now that Islamic State has been driven out of cities in Iraq and Syria. “We’ll be coming out of Syria, like, very soon. Let other people take care of this now.” In another move connected with his desire to disengage from Syria, Trump froze $200 million in stabilization aid intended for Syria.

Within 24 hours, however, Washington was singing a slightly different tune.

Trump’s press secretary, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, said that the United States is committed to finishing its mission of eradicating the remnants of Islamic State in Syria, which has been embroiled in a civil war for the past seven years.

Pentagon officials, claiming that the rise of Islamic State was made possible by President Barack Obama’s decision to withdraw U.S. troops from Iraq in 2011, warned that American gains in Syria could be squandered by a premature American pullout. This point was underscored by General Joseph Votel, the commander of the U.S. Central Command. “A lot of very good military progress was made over the last couple years,” he said, implying that the United States still has unfinished business in Syria.

Critics contend that a hasty U.S. withdrawal could be disastrous — facilitating the return of Islamic State in certain areas of Syria, letting Russia reestablish a foothold in the Middle East, and allowing Iran and its client, Hezbollah, to build a military infrastructure in Syria to confront Israel.

Israel, of course, is worried by the drift of American policy.

Last month, Israeli Public Security Minister Gilad Erdan said, “Let me be direct. There is a need for greater American involvement in making sure that Iran doesn’t turn Syria into a puppet state. Every day that Iran entrenches itself in Syria brings war closer. If the U.S. chooses not to be a major player in shaping the future of Syria, then others will.”

At the beginning of April, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in a telephone call with Trump, expressed concern about his desire to get out of Syria. After the conversation, the White House issued a soothing statement reaffirming the United States’ commitment to Israel’s security and its interest in “countering Iran’s malign influence and destabilizing activities” in Syria.

Trump’s conciliatory words reassured Netanyahu, but the flip-flop tone of U.S. pronouncements on Syria is still a source of consternation to Israel and Sunni Arab countries like Saudi Arabia and Jordan.

Until quite recently, U.S. policy in Syria seemed more coherent.

In 2014, following Islamic State’s seizure of large swaths of territory in Syria and Iraq, Obama ordered air strikes on IS positions in both countries, promising to “degrade and ultimately destroy” this Islamic fundamentalist movement.

When he entered office, Trump said that his objectives were to eradicate Islamic State, support rebels opposed to Assad, back diplomatic efforts to settle the civil war, and deliver humanitarian aid to besieged Syrian civilians caught in the crossfire between pro-Assad and rebel forces.

Trump intensified air strikes against Islamic State, sent more troops to Syria, and solidified the United States’ alliance with Kurdish militias and Syrian Arab groups facing Islamic State on the battlefield. Yet by aligning itself so closely with the Kurds, the United States angered Turkey, a NATO ally whose army has pushed into northern Syria to protect its southern border.

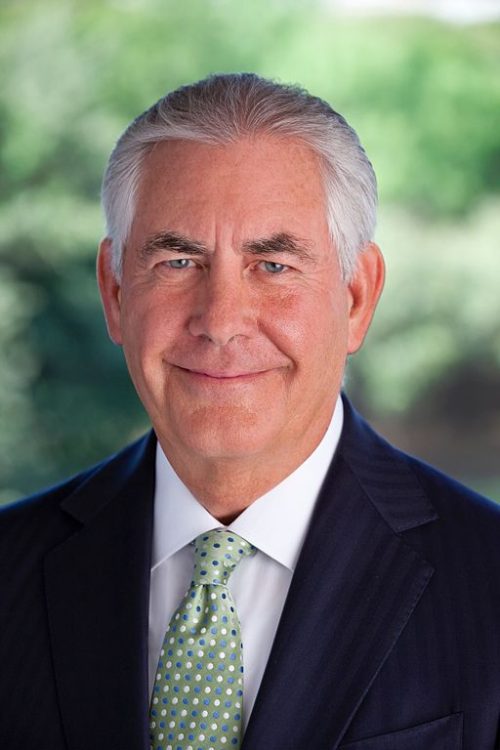

Before his dismissal as secretary of state in March, Rex Tillerson clearly enunciated U.S. goals in Syria in an early new year speech at Stanford University: to prevent Islamic State from regrouping, to thwart Iran from entrenching itself militarily, to avoid conflict with Turkey, to ease Assad out of power, to endorse United Nations-sponsored talks in Geneva to end the civil war, and, in general, to maintain a military and diplomatic presence in Syria.

Since Tillerson’s removal from office and his replacement by Mike Pompeo, the former director of the Central Intelligence Agency, U.S. strategy has not been as cogent. Certainly, compared to Russia’s clear-eyed policy, the United States is, at best, muddling through.

President Vladimir Putin, determined to project Russian power in Syria and the Middle East, backs Assad’s regime unreservedly. Russia and Syria have longstanding political and military relations, and Putin is consolidating their mutually beneficial relationship. Two and a half years ago, he sent a squadron of aircraft to Syria to prop up Assad’s government. By doing so, he helped turn the tide of the war in his favor.

On the political front, Russia has outflanked the United States. Russia, in tandem with Turkey and Iran, have created the Astana peace process, which has eclipsed the United Nations-backed Geneva talks. Last week, the presidents of Russia, Turkey and Iran met at a trilateral summit in Ankara to plan their next move.

Tellingly enough, the United States was not invited, leaving it out in the cold.

Jennifer Cafarella, the lead intelligence planner at the Institute for the Study of War, argues that the tenor of American policy leaves much to be desired. As she put it, “U.S. behavior in Syria signals that we do not have the will to defend our interests or commit the resources necessary to achieve our stated goals.”