Canadian historian John-Paul Himka has written an illuminating, important, ground-breaking and grim book about an exceedingly dark chapter in Ukraine’s history.

It goes without saying that most Ukrainians would probably prefer to shove this terrible, blood-soaked interregnum under the carpet, all the more so since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24.

Himka, a professor emeritus at the University of Alberta and an ethnic Ukrainian, has produced a sober and meticulous account of the role played by far right-wing Ukrainian nationalists in the mass murder of Jews during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine and Poland.

Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust, published by Ibidem and distributed by Columbia University Press, concerns the participation of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and its armed force, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), in the mass murder of Jews in Ukraine from 1941 to 1944.

Upwards of 1.5 million Jewish Ukrainians were killed during the German occupation, a ghastly death toll comprising about 25 percent of the victims of the Holocaust, says Himka, whose niece, Chrystia Freeland, is Canada’s current deputy prime minister and finance minister. (She has inexplicably refused to acknowledge or condemn her maternal grandfather’s role in the demonization and murder of Jews in Poland).

Ukrainian apologists who have striven to distance OUN and UPA from these atrocities will have to reassess their false and self-serving perspective after reading this eye-opening book.

By Himka’s clinical reckoning, OUN and UPA worked closely with the Nazi authorities and were deeply implicated in all aspects of Germany’s genocidal war in Ukraine, which was part of the Soviet Union until it achieved independence in 1991.

In the summer of 1941, following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, militias organized by OUN arrested Jews and subjected them to a horrifying regimen of forced labor, humiliation and murder. During 1942 and 1943, OUN recruited personnel for police forces in Galicia and Volhynia, which were located in Poland but which together comprised Western Ukraine. These units rounded up Jews for deportation to the Belzec extermination camp in Poland.

Early in 1943, UPA launched a massive ethnic cleansing campaign, first in Volhynia and then in Galicia. It was directed against Poles as well as Jews. In 1944, UPA bands murdered Jews after they emerged from their hiding places in forests.

For almost 50 years after World War II, this emotionally-charged topic eluded scholars because local archives were closed to them. After they were opened in the 1990s, a new wave of historians began investigating this calamitous period. Himka mentions these individuals in his first chapter, giving them due credit for their scholarly contributions. In addition, he makes laudatory references to prewar historians such as Philip Friedman, who specialized in the study of Galicia’s Jewish population.

Himka, too, reminds readers that Ukrainian governments since the presidency of Viktor Yushchenko have honored morally compromised figures like Roman Shukhevyych, the commander of UPA, and Stepan Bandera, the leader of a radical OUN faction. Yushchenko’s successor, Viktor Yanukovych, rolled back the cult of OUN, but it returned after the upheavals of 2014.

Himka explores the origins of OUN in another chapter. It was founded in Vienna in 1929 to represent Ukrainians in Ukraine, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Romania. By Himka’s estimate, its membership was as high as 40,000.

Its first leader, Yevhen Konovalets, was at its helm until his assassination in 1938. His replacement, Andrii Melnyk, led OUN until 1940, when Bandera challenged his leadership and formed OUN-B, whose red and black emblem symbolized the Nazi concept of blood and soil. From that point onward, Melnyk’s faction was known as OUN-M.

During the 1930s, OUN turned radically anti-communist, its membership outraged by the famine in the Soviet Union which claimed the lives of several million Ukrainians. Its rightward lurch was championed by Dmytro Dontsov, a former Marxist and a Ukrainian newspaper editor who praised Adolf Hitler and his antisemitic policies. Dontsov was not a member of OUN, but he was influential among Ukrainians, especially in Galicia.

OUN, a fascist organization, aligned itself with Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. “OUN borrowed heavily from Italian fascism and … from German national socialism,” Himka writes. “It believed in dictatorship, an authoritarian leader, corporatism, censorship and political violence against opponents.”

By the mid-1930s, he adds, antisemitism had become an integral component of its ideology. One of its newspapers, Novo selo, compared the struggle against Jews with the struggle against communism.

Yaroslav Stetsko, an OUN ideologue who claimed that Jews exploited Ukrainians in commerce, insisted they were the most ardent supporters of the communist regime in Moscow and formed the advance guard of Russian imperialism in Ukraine.

Still others in OUN charged that Jews opposed Ukrainian statehood. In spite of its visceral animus toward Jews, OUN regarded Russians and Poles as its chief enemies. “Jews were of secondary importance,” says Himka.

Ukrainian stereotypes regarding the connection of Jews to communism seemed to be borne out by the preponderance of Jews in the Soviet administration in eastern Poland after its conquest by the Red Army in September of 1939.

But while Jews were safe under Soviet rule and were no longer exposed to antisemitic attacks, their businesses were nationalized, their cultural organizations were banned, their political parties were liquidated, and their Zionist and Bundist activists were arrested.

With Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, a rash of pogroms erupted in territories the Soviets had acquired in 1939 and 1940 under their non-aggression pact with the Nazi regime. “Wherever the Nazis went, they orchestrated pogroms,” says Himka, adding that OUN assisted the Germans in this murderous rampage, especially in Galicia and Volhynia.

“The anger of the population turned on ‘the Jews,’ who were widely, though inaccurately, perceived to have been the main support of the Soviet regime,” he says.

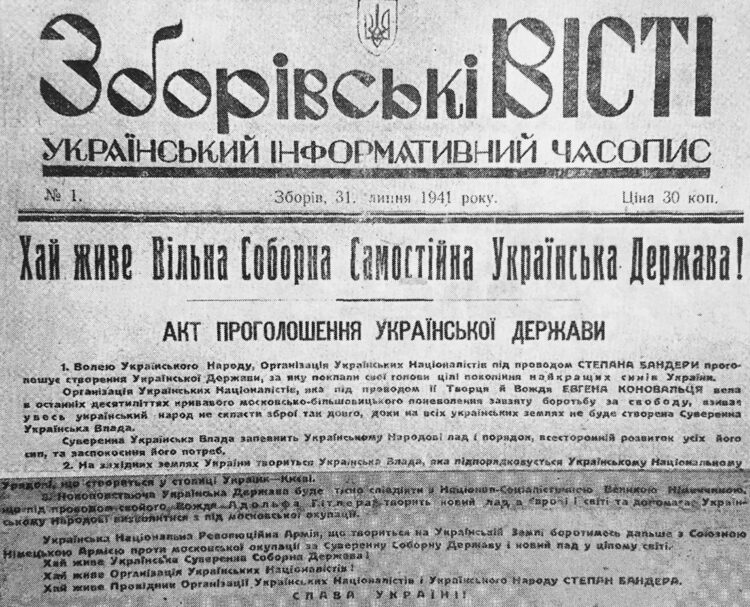

With the arrival of the Germans in Lviv on June 30, OUN declared Ukrainian statehood and issued a proclamation declaring that “the renewed state” would “collaborate closely with National Socialist Germany, which under the leadership of Adolf Hitler is creating a new order in Europe and the world and is helping the Ukrainian people liberate themselves from Muscovite occupation.”

Much to OUN’s surprise And disappointment, Germany declined to recognize Ukraine’s declaration of statehood, and proceeded to arrest Bandera and Stetsko, who supported the extermination of Jews on the supposed grounds that they were allies of the Soviet Union.

During this unsettled period, OUN distributed flyers in Lviv urging Ukrainians to slaughter communists, Jews, Poles and Hungarians. The resulting pogroms, perpetrated by OUN militias and German mobile killing squads, the Einsatzgruppen, caused the deaths of thousands of Jews.

With Lviv occupied by the Germans, this cosmopolitan city of Ukrainians, Poles and Jews was administered by OUN, which was complicit in the marginalization, isolation and persecution of its Jewish residents.

Ukrainian officials were involved in the identification, registration and exploitation of Jews and in the distribution of their household goods after they were murdered. Local Ukrainians also pressed Jews into forced labor projects and were active in establishing ghettos. OUN’s antisemitic campaign extended into other cities as well.

In isolated instances, Ukrainian policemen rescued Jews and warned them of impending raids, says Himka.

By the spring of 1942, OUN-B, having realized that its association with Germany was becoming a liability abroad, issued a statement: “Notwithstanding the negative attitude to Jews as an instrument of Muscovite-Bolshevik imperialism, we consider it inexpedient at the present moment … to take part in anti-Jewish activity …”

Nonetheless, OUN-B distributed a flyer in western Ukraine proudly acknowledging its participation in the murder of “the Muscovite-Jewish occupier.” And toward the end of that year, OUN-B issued a resolution that “Jews should not be destroyed, but resettled from Ukraine …”

Swayed by the erroneous perception that Jews exerted disproportionate influence in western democracies like the United States and Britain, OUN-B noted, “It is necessary to be careful with them …”

Despite its expedient declarations, OUN-B continued to distribute antisemitic leaflets admonishing Ukrainians to kill Jews. “They murdered every Jew who crossed their path or had found a hiding place,” Himka quotes Jewish survivor Lea Rog as saying.

UPA, in Volhynia and Galicia, also murdered Poles in accordance with its ethnocentric slogan, “Ukraine for Ukrainians.”

“In the fierce war between Poles and Ukrainians, many Jews chose the Polish side, or had that side chosen for them,” says Himka.

However, as he observes, a small number of Jewish physicians, paramedics, nurses and dentists joined UPA, which was in dire need of such medical professionals. They were frequently forced to conceal their Jewish background to survive.

Antisemitism was so profoundly rooted in the ranks of OUN that it persisted even after the war, says Himka. Interrogated by his Soviet captors, OUN activist Volodymyr Porendovsky told them that it preached an openly racist ideology that called for the annihilation of Jews. Dmytro Maievsky, the director of OUN’s political bureau, said, “It was a good thing that the Germans annihilated the Jews, because in this way OUN got rid of some of its enemies.”

Since the war, OUN apologists have tried to hide or gloss over its wartime crimes by blaming them on criminal and lumpen elements, Himka says.

“Neither OUN nor UPA as organizations attempted to rescue Jews. As organizations, they killed Jews. But individuals within these organizations were sometimes moved to spare people they knew or who awakened their sympathy.”

Himka goes on to write, “Once we dismiss these deliberate mystifications, we can examine OUN’s record during the Holocaust in its proper light. What we see is that in the second half of the 1930s … OUN expressed its solidarity with Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and antisemitic Romania. It propagated antisemitism and particularly the concept of Judeo-communism, and its ideologues began to envision a Ukrainian state that was both imperialist and cleansed of non-Ukrainian minorities.

“From late June and at least into early August 1942, OUN militias killed Jews throughout Galicia, Bukovina and Volhynia, sometimes helping the Germans or Romanians, and sometimes just on their own leadership’s initiative.”

Himka acknowledges that the Germans created a “poisonous atmosphere” by words and deeds. But in a devastating indictment, he says, “It needs to be understood that OUN itself did much to spread anti-Jewish sentiment and to encourage anti-Jewish violence in the general population of Galicia, Volhynia and Bukovina.”

To say that OUN and UPA have blood on their hands would be a ringing understatement. This is the awful legacy that haunts Ukrainians today as they fight for their independence in a grinding war with Russia, their perennial nemesis.