They are usually small in area and population, ethnically and religiously homogenous, well-off and situated in a peaceful part of the world, alongside neighbours who have no designs on them.

What are they? Countries which go virtually unnoticed internationally. Yet they can be quite interesting.

The quintessential example? Uruguay.

A settler state like its big neighbor Argentina, which lies across from it, separated by the mouth of the Rio de la Plata, Uruguay’s population of 3.32 million is composed almost entirely of Spanish and other European immigrants.

At 176,215 square kilometers, it is the second-smallest country in South America. Its only other neighbor is Brazil, and it has historically served as a buffer between these two South American giants.

Uruguay became wealthy from the export of livestock to Europe, and it became the world’s first welfare state. The capital, Montevideo, became a major economic center of the region.

But in the late 1950s Uruguay began having economic problems, which included inflation, mass unemployment, and a steep drop in the standard of living for Uruguayan workers.

This led to student militancy and labor unrest. An urban guerrilla movement known as the Movimiento de Liberacion Nacional-Tupamaros was formed in the early 1960s, robbing banks and distributing food and money in poor neighborhoods, and undertaking political kidnappings and attacks on security forces.

Democratic institutions could not withstand the strain. In 1968, President Jorge Pacheco brought in a state of emergency. His successor, Juan Maria Bordaberry, repealed all constitutional safeguards in 1972 and brought in the army in to combat the guerrillas.

They not only defeated the insurgents but mounted a coup in 1973. The dictatorship would last 12 years.

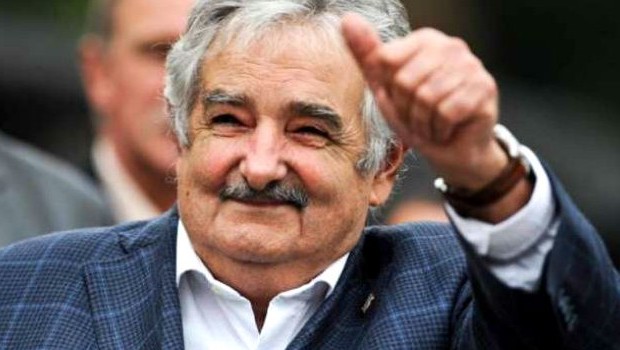

The country has in recent decades returned to its progressive orientation. In the 2009 election, the winner was José Mujica, who had been a Tupamaro himself. He spent 14 years in captivity, 10 of them in solitary confinement.

Under Mujica, Uruguay has emerged as a laboratory for socially liberal policies. The country has also enacted a groundbreaking abortion rights law, legalized same-sex marriage and is becoming a center for renewable energy ventures.

Why is Uruguay so liberal? “We’re a country of immigrants, anarchists and persecuted people from all over the world,” Mujica explains.

The first record of Jewish settlement in Uruguay is in the late 18th century. Today, Uruguay boasts a Jewish population of approximately 17,300 — the fourth largest Jewish community in South America. Almost all of them live in Montevideo.

The modern community traces itself back to the late-nineteenth century. Most were Sephardim and Mizrachim from places such as Syria, Morocco Egypt, Greece and Turkey. By 1909, 150 Jews lived in Montevideo, the city with the largest Jewish population. Despite the history of settlement, the community did not open its first synagogue until 1917.

Most of the Jews who subsequently arrived were Ashkenazim, the majority of them immigrating in the 1920s and 1930s, including German Jews fleeing Hitler.

From the 1930s until about 1950, there were several failed attempts at creating Jewish agricultural settlements in Uruguay.

Uruguay was one of the first nations to recognize Israel, and the first Latin American country to do so. It was the first Latin American country and fourth country overall in which Israel established a diplomatic mission. It was also one of the few nations to support Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and oppose internationalization of the city.

There is a strong secular leftist tradition. Indeed, the Jewish Communists, a group that once numbered in the thousands, refused to be part of the structured religious community, and organized themselves into a sub-community.

During the 1930s, along with Jews in Argentina, they created PROKOR (Proletarishe Kolonizatsye Organizatsye), a support group for Jewish settlement in Birobidzhan in the Russian far east, where the Soviet Union had created an autonomous region for Jews.

In the wake of the Latin American economic crisis of the early twenty-first century, Uruguayan Jews were hit hard. Between 1998-2003, more than half of the community’s 40,000 Jews have immigrated, mostly to Israel.

A few dozen Jews were involved with the Tupamaros. One of its four leaders was Mauricio Rosencof, the son of Polish Jews immigrants, who was arrested in 1972 spent 13 years in a military prison.

Today he is a well-known Uruguayan playwright, poet and journalist from and since 2005 he has been director of culture of the Municipality of Montevideo.

It turns out there’s plenty of news from Uruguay.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.