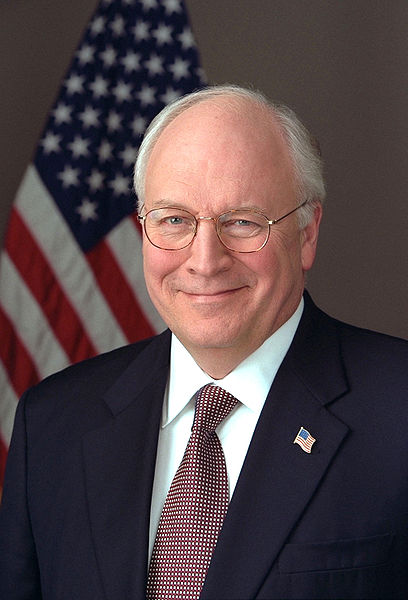

Dick Cheney, George W. Bush’s two-term vice-president, emerges as the power behind the throne in Adam McKay’s sardonic film, Vice, which takes a dim view not only of Cheney but of Bush and many of the major figures in his administration.

Superbly portrayed by Christian Bale, a British actor who imitates his monotone mid-western accent with uncanny accuracy, Cheney is seen as a calculating and disciplined politician who manipulated a lightweight president (Sam Rockwell) as the United States was drawn into wars in Afghanistan and Iraq following the Arab terrorist attacks in Manhattan and Washington, D.C. on September 11, 2001.

Before dwelling on this tumultuous period, McKay goes back to the days when the younger Cheney seemed like a lost cause in terms of his ambition and willingness to succeed. In a pivotal scene several minutes into this vivid movie, Cheney’s strong-willed wife, Lynne (Amy Adams), threatens to leave him unless he has the “courage to become someone.” Forcing him to straighten himself out, she says, “Can you change, or am I wasting my god-damn time?”

Chastened by her demand, Cheney promises he won’t disappoint her again.

At this juncture, he’s a diamond-in-the rough, willing to polish his persona and blend in. Hired as an assistant to Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carell), a cynical and profane official in the Nixon administration and the secretary of defence under Bush, Cheney pronounces himself to be a Republican in order to please Rumsfeld, his mentor.

After Rumsfeld is named U.S. ambassador to NATO, Cheney becomes President Gerald Ford’s chief of staff. Losing that position when Jimmy Carter succeeds Ford, Cheney runs for Wyoming’s only congressional seat, but suffers a heart attack during the campaign. His wife fills in for him and wins over skeptical voters, catapulting Cheney to Washington D.C. Cheney’s cardiac problems figure prominently as the film unfolds.

McKay glosses over Cheney’s role as secretary of defence. He’s far more interested in examining his reaction to the disclosure that one of his daughters, Mary (Alison Pill), is gay. When she breaks the news to him, he gives her a hug and says he loves her. In this respect, Cheney is a man of compassion and a loving father. Lynne, on the other hand, keeps her distance from Mary as she leaves the closet.

When Bush asks him to be his running mate, Cheney demurs. He and Lynne have already discussed that possibility, but she is dismissive of the vice-presidency. “The vice-president is a nothing job,” she says scornfully. He agrees. During his meeting with Bush, Cheney offers to help him find a suitable candidate. When they meet again, Bush again asks Cheney to serve as his vice-president. He accepts after Bush promises to invest him with powers that very few vice-presidents have ever had.

Once Bush is inaugurated, Cheney places his cronies in strategic positions in the Bush administration, promotes the war on terrorism and pushes for an invasion of Iraq. “No doubt Saddam Hussein has weapons of mass destruction,” he claims in what will be the chief pretext for unseating the Iraqi president in 2003.

Colin Powell (Tyler Perry), the American secretary of state, opposes Cheney’s plan, but goes along with the flow, a decision he will regret. As he prepares to announce that the invasion has begun, Bush turns to Cheney and asks, “How’s my hair?” So much for Bush.

Cheney remains certain that U.S. policy on Iraq was correct. “I will not apologize for what needed to be done,” he declares.

McKay begs to differ with his analysis and his critique of Cheney colors Vice from beginning to end.