We have just commemorated the 70th anniversary of D-Day, June 6, 1944, when the liberation of France began. But four years earlier, a defeated France had effectively become a fascist state — and it’s amazing how quick was the transformation.

Within a few weeks of the country’s invasion by Nazi Germany on May 10, 1940, the French government surrendered and signed an armistice with Adolf Hitler on June 22. (Remember, France was not conquered, the way Belgium or Poland were, so had no government-in-exile that had escaped the country.)

The armistice gave Germany control over the north and west of the country, including Paris and all of the Atlantic coastline, but left the rest, around two-fifths of France’s prewar territory, unoccupied.

And almost immediately, the country was transformed into an authoritarian state. On July 10, 1940, the French National Assembly, summoned to ratify the armistice, granted the hero of France’s success in World War I, 84-year-old Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain, authority to promulgate a new constitution. The vote, 569 in favour, 80 against, 18 abstentions, wasn’t even close.

The Third Republic ceased to exist.

Pétain was able, the very next day, to assume in his own name full legislative and executive powers in the new political order. The République Francais was replaced by l’État Francais , the republican slogan “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” (“Liberty, Equality, Brotherhood”) by “Travail, Famille, Patrie” (“Work, Family, Fatherland”). The French tricolour flag now included in the middle Pétain’s personal emblem, a stylized francisque, an axe said to have been used in the early Middle Ages by the Franks.

The national holiday, Bastille Day, became a day of mourning, and the stirring French national anthem, the “Marseillaise,” gave way to a song of praise, “Maréchal, Nous Voila !” (“Marshal, Here we Are!”) for Pétain. He was now the “Chef de l’État Francais,” his portraits soon everywhere.

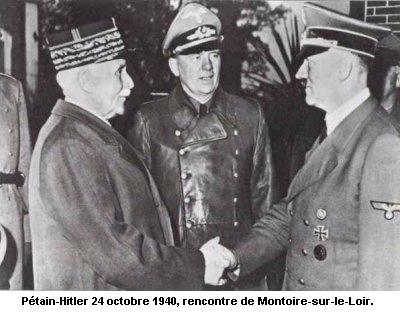

The Vichy government declared neutrality in the war between Germany and Britain, but was committed by the armistice provisions to cooperation with Germany. The aged Pétain now had become a Nazi collaborator – even though he had briefly served as prime minister in the last democratic government. There is an infamous photo of him shaking hands with Hitler on Oct. 24, 1940, in the town of Montoire-sur-le-Loir.

The Vichy prime minister and head of day-to-day governance between April 18, 1942 and August 20, 1944, Pierre Laval, had twice served as a prime minister in the Third Republic in the 1930s.

Vichy France, as the country became known — because the collaborationist regime was located in the town of Vichy, in the southern “unoccupied zone” — remained, even in the eyes of the Allies fighting Germany, the sovereign and legitimate government of France, technically ruler over the entire country.

Vichy continued to be recognized as such by, among others, Canada and the United States, for at least two more years.

French colonial officials in the country’s overseas empire also at first were loyal to Vichy — as everyone who has seen the 1942 movie Casablanca knows. In one of the film’s very first scenes, the wall of a building is painted with a large picture of Marshal Pétain and a quote attributed to him.

In the first years after the 1940 defeat, much of the war-weary French population fell in behind Pétain. General Charles de Gaulle, who had fled to England after the fall of France, faced a lonely uphill battle at first, as he formed the Free French forces abroad and encouraged the anti-Nazi resistance inside France. The French flag, with the Cross of Lorraine in the centre, was the emblem of the Free French.

Pétain blamed the Third Republic and its endemic corruption for the French defeat. He rejected its secular and liberal traditions in favour of an authoritarian, paternalist, Catholic society. Vichy even produced a legion of volunteers to fight against Soviet Russia.

As Princeton University historian David Bell has written, a portion of France’s elites treated the crushing defeat of 1940 “as history’s judgment on a corrupt and senile society,” and therefore were willing “to embrace Hitler’s grotesque New Order rather than to struggle against it.”

But Vichy’s so-called “Révolution Nationale” (“National Revolution”) included the passage of numerous antisemitic laws. When France fell, there were approximately 350,000 Jews in the country. As early as October 1940, without any request from the Germans, the Vichy government passed anti-Jewish measures.

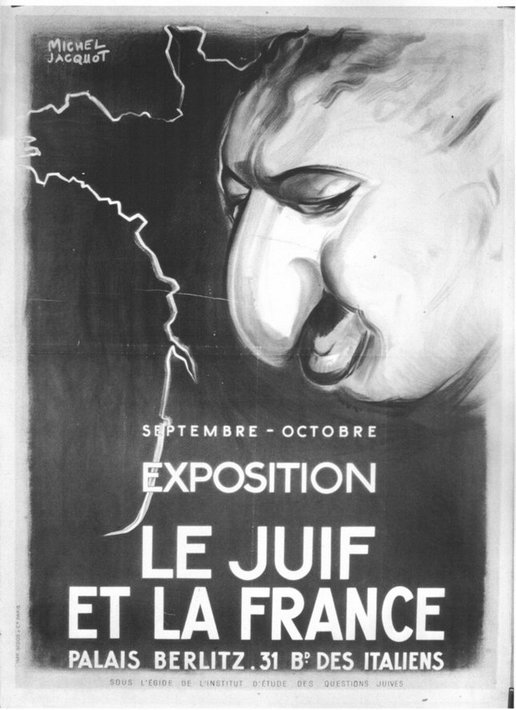

In 1941 the regime mounted a major antisemitic exhibition, Le Juif et la France (The Jew and France), in Paris, depicting the Jews as a criminal race responsible for all of France’s problems. It is estimated that around 200,000 people visited the exhibition.

French Jews were denaturalized, and in many cases rounded up by French (not German) police and sent to death camps. According to historian Robert Paxton, some 90.000 Jews living in France were killed in the Holocaust.

In 1995 President Jacques Chirac publicly recognized France’s responsibility for deporting thousands of Jews to Nazi death camps during the German occupation. His statement put an end to decades of equivocation by successive French governments about France’s wartime role.

The French Vichy regime remains a cautionary tale, as it demonstrates how quickly a democratic political order can be reversed.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.