I was disappointed, though not really surprised, by the news that the 19th century villa of Yechezkel Sasson, in central Baghdad, was recently demolished.

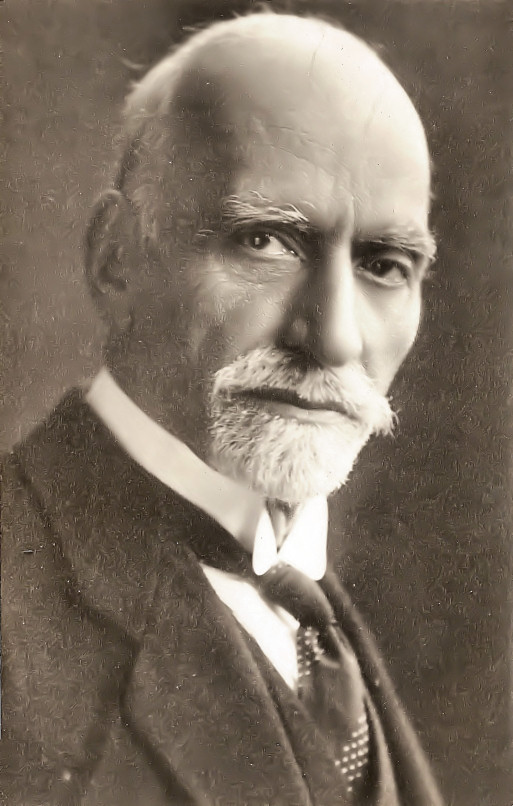

Sasson, who was usually known as Sir Sassoon Eskell, was the scion of a distinguished Iraqi Jewish family and one of the founders of modern Iraq. Along with T.E. Lawrence, Gertrude Bell and a number of other colonial officials, he was instrumental in the formation of the Kingdom of Iraq under British administration after World War I.

From 1920 to 1925, Eskell — a cousin of the British poet Siegfried Sassoon — was minister of finance in five successive governments. He was also a member of parliament and chairman of its finance committee. As described by Bell in her diaries, Eskell was competent and conscientous.

During the 1920s, when Eskell was at the height of his renown, Iraq was home to more than 100,000 Jews, whose ancestors reached Mesopotamia during the era of the Babylonian captivity. The Jews of 20th century Iraq, concentrated in Baghdad, were well integrated, but the rise of Arab nationalism and the intensification of the clash between Zionism and the Palestinian national movement ultimately doomed the venerable Jewish community.

The pogrom that erupted in Baghdad in June 1941, claiming the lives of some 200 Jews, was the first tangible sign that the community’s days might be numbered. Israel’s declaration of independence in 1948, which prompted five Arab nations, including Iraq, to invade the new Jewish state, triggered a wave of repressive measures against Jews. As a result, all but about 10,000 Jews left Iraq, the vast majority immigrating to Israel.

Eskell died long before these catastrophic events.

Despite the esteem in which he was apparently held as a civil servant and patriot, the city of Baghdad had no qualms about selling his historic, two-storey villa to a developer. He, in turn, tore it down to make way for a high-rise condominium complex.

According to reports, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities lobbied to save the villa, having classified it as a priceless heritage site. But the municipality paid no heed and allowed the demolition go ahead.

The villa, which was located in a sedate neighborhood, was architecturally striking. As Najem Wali, an Iraqi exile living in Germany, wrote in 2011, “Everything about it is beautiful: the curves of the arches, the doors, the balustrades on the roof, the wooden-framed windows, the sweeping balcony high above the Tigris River. It’s almost as if each stone of the house, set back slightly from historical Al Rashid Street, had been gently stroked and lovingly formed by the master’s hand.”

The fate that befell Eskell’s villa was, perhaps, inevitable.

With the downfall of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime in 2003, following the U.S. and allied invasion of Iraq, civil disorder and an insurrection engulfed the country. Museums were looted. Archeological sites were plundered. Shops were ransacked. Suicide bombs were detonated.

Jewish sites were particularly vulnerable, as Iraqi historian Nabil al-Rube’l told the Israeli daily Maariv.

During this period of upheaval, Eskell’s private library, the largest of its kind in Iraq, was looted. In Najem Wali’s estimation, it was a splendid library. As he wrote, “It was said that the books were spread out in almost every room of the house, with works in many languages — Arabic, Turkish, English, French, Italian, Spanish and German. All the languages Eskell could speak fluently.

By then, scarcely any Jews still lived in Iraq, many having fled after the Baath Party’s coup in 1963. Still others departed after the public hanging, in 1969, of nine Jews falsely accused of spying for Israel.

Rube’l claims that the demolition of Eskell’s villa was met with “great sadness.” As he told Maariv, “Every Iraqi intellectual, or even just anyone interested in the country’s past, knows who Yechezkel Sasson was.”

The wanton destruction of his villa was certainly an act of vandalism cloaked in the aura of legality, urban development and progress. But the saga of mankind, regrettably, is littered with such desecrations.

In the Spanish city of Cordoba, a magnificent mosque, a masterpiece of Moorish architecture, was converted into a cathedral. And in Istanbul, the Hagia Sophia Greek Orthodox church was turned into an Ottoman mosque. Much of the campus of Tel Aviv University lies on the ruins of the Palestinian Arab village of Sheikh Muwannis. And the affluent Tel Aviv neighborhood around Arlosorov and Ibn Gvirol was built on land belonging to Summeil, a village once inhabited by Palestinian Arabs.

History can indeed be cruel, as the demolition of Eskell’s villa demonstrates yet again.