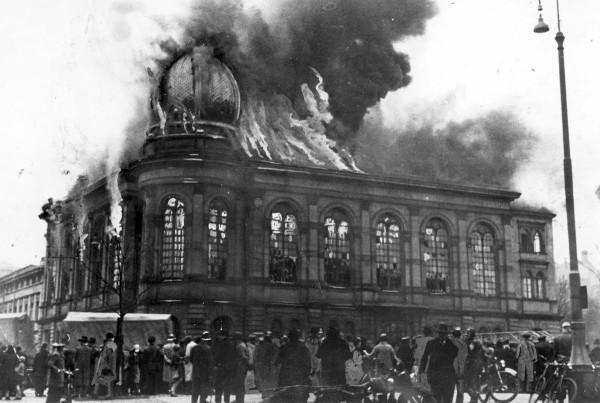

Synagogues were an integral part of cityscapes in Germany before the Nazi era, nearly as common as churches. With about 500,000 Jews, Germany had one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe. But during the two-day Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938, the worst since medieval times, Nazi mobs destroyed more than 1,500 synagogues, or practically every shul in the country.

Thanks to a German professor of architecture at the Technical University in Darmstadt, a handful of these synagogues have been restored, at least in digital form.

Since 1994, when the project was launched, Marc Grellert and his students have digitally reconstructed the exteriors and interiors of 25 synagogues in cities ranging from Berlin and Munich to Frankfurt and Dresden.

The project, known as The Synagogues in Germany — A Virtual Reconstruction, recreates a vanished world and speaks to the power of computer technology to resurrect the past.

Grellert, 51, was in Toronto recently to talk about it during Holocaust Education Week.

Grellert, whose late grandfather was a member of the Nazi Party, was a graduate student when the idea occurred to him. A synagogue in the northern city of Lubeck had been firebombed, the first such incident of its kind in Germany since the 1930s, and Grellert was shocked and appalled.

“After the arson attack, I wanted to raise a protest against racism and antisemitism and to pay tribute to the architectural importance of the synagogues” he said. “I was interested in the connection between architecture, society and minorities.”

The concept fascinated Grellert’s advisor, Manfred Koob, then the chairman of the university’s faculty of architecture. I interviewed Koob in Darmstadt 15 years ago. He died in 2011.

“We went into this not knowing anything about synagogues,” said Koob. “My generation knew nothing about Jewish culture.”

Beyond everything else, he added, the project was designed to underscore the view that Jews and Judaism are not alien to Germany, Nazi ideology notwithstanding.

The seven students who originally joined the project felt they had a special responsibility to German history. “They understood what was destroyed,” said Koob, who had never met a Jew before immersing himself in the project. “The point was to recreate a consciousness of what was lost.”

Since then, more than 70 students have worked on the project.

To prepare themselves for the task, Grellert and Koob enlisted the aid of local Jewish communities and scoured archives for blueprints, photographs and illustrations. They also talked to Jews who had worshipped in Moorish, German Romanesque, Neo-classical and Bauhaus-style synagogues they wished to rebuild in digital form.

Under Koob’s overall guidance, the project started with the virtual rebuilding of three Frankfurt synagogues that had been constructed in 1860, 1881 and 1907. From there, the team reconstructed the Glockengasse synagogue (1861) in Cologne, the Senefelderstrasse/Ecke Engelstrasse synagogue (1930) in Plauen, the Bergstrasse synagogue (1870) in Hannover, the Herzog-Maxstrasse synagogue (1887) in Munich and the Fasanenstrasse synagogue (1912) in Berlin.

These were grand buildings, reflecting the self-confidence of the Jewish community in the second half of the 19th century and the first third of the 20th century.

The reconstructions are more or less accurate, true to architectural nuances and colors. “The objective is to convey an impression, not an exact facsimile,” explained Grellert. “I was interested not only in creating beautiful images, but in generating an interest in Jewish culture. So it’s a political project too. I knew very little about Jewish history in Germany when I began.”

From the outset, Grellert decided he would not solicit funds from the Jewish community. As a German, he thought, he had a “historic responsibility” to launch the project without the assistance of Jews. The federal government and municipalities, however, provided financial help.

Since the project’s inception 21 years ago, it has gone on exhibit all over Germany and travelled to Israel and the United States as well. Canada may be next, Grellert hopes.

Much to his satisfaction, it’s still going strong.

A documentary film displaying three-dimensional images of virtual synagogues has been produced. An interactive archive of some 2,200 synagogues that were closed, vandalized or sacked during the Third Reich is now available online.

And, as Grellert disclosed, he and his students are almost finished building a digital synagogue in Bamberg. It’s expected to be ready by the end of this year.