At his peak in the 1930 and 1940s, syndicated columnist and radio personality Walter Winchell commanded an audience of an estimated 50 million American readers and listeners. Blending news and entertainment, he single-handedly created the gossip-driven, politically-charged media culture of the United States.

“Winchell is the architect of modern American media,” says his biographer, Neal Gabler. “He turned journalism into a form of entertainment.”

Ben Loeterman’s absorbing biopic, American Masters — Walter Winchell: The Power of Gossip, will be broadcast by the PBS network on Tuesday, October 20 at 9 p.m. (check local listings). It is narrated by Whoopi Goldberg. Winchell’s breathless newspaper columns and broadcast scripts are read by Stanley Tucci.

The son of poor Russian Jewish immigrants, Winchell was born in Harlem in 1897. Dropping out of school in the sixth grade, he launched what would be an undistinguished 10-year career as a vaudeville entertainer.

His wife, a performer in the same troupe, changed his life by presenting him with an invaluable gift — a typewriter. He used it to post juicy tidbits about his fellow performers on backstage bulletin boards. Winchell had a knack for breezy narrative, despite his utter lack of training as a newspaperman.

In 1924, The New York Evening Graphic, a licentious and sensationalist tabloid, offered him employment as a Broadway columnist. Revelling in his role as a muckraker, he instinctively understood that gossip was a way to take down the high and mighty and empower readers.

Stylistically, he was an innovator, writing in short, sharp, crisp sentences, inventing new words, and trading in innuendo.

The New York Daily Mirror hired him in 1929. As his popularity grew, he branched into radio. His audience was “Mr. and Mrs. America.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt, the newly-elected president, invited Winchell to the White House in 1933 and, in a 10-minute meeting, seduced him. From that point forward, Winchell, a liberal, fervently supported Roosevelt’s reformist New Deal policies.

He could often be found in Manhattan’s elitist Stork Club, one of the hubs of New York City’s celebrity culture, where he mingled with press agents, actors, gangsters, socialites and politicians.

Totally devoted to his job, he was a night owl, prowling the streets of New York in a car fitted with a police scanner and a siren. These devices helped him hunt down fresh stories and acquire scoops.

Unbeknownst to his readers, many of his columns were ghost written by a reporter named Herman Klurfeld.

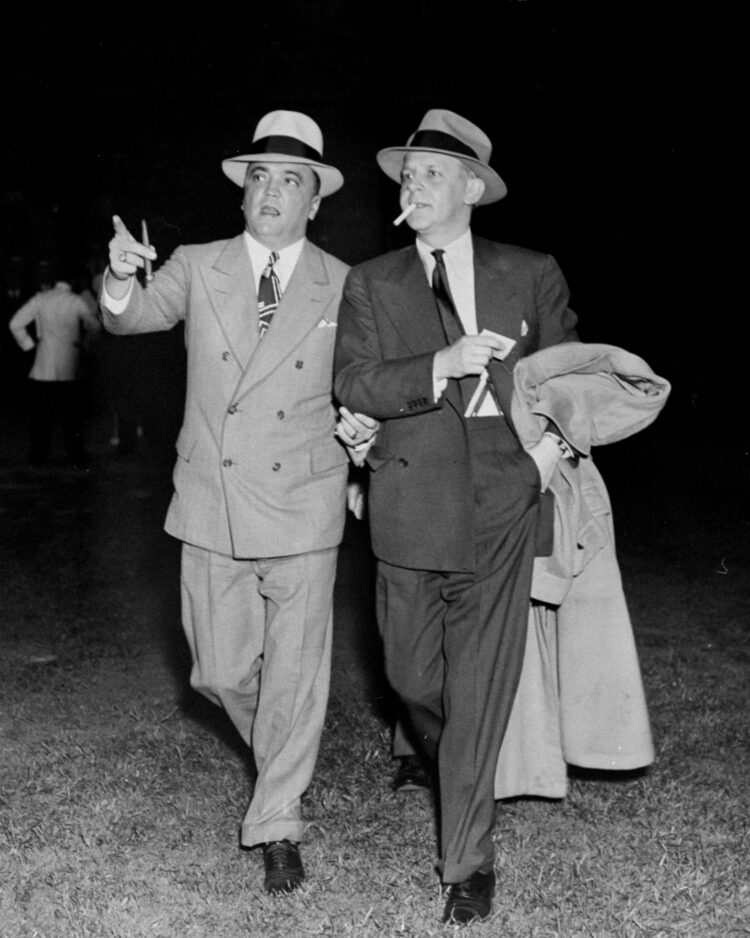

Winchell boasted of a wholesome home life, but he was enmeshed in constant affairs. One of his best friends was the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, with whom he shared and weaponized secrets.

Winchell despised and ridiculed Adolf Hitler, the Nazi chancellor of Germany whose masculinity he challenged. He also poked fun at Fritz Kuhn, the pro-Nazi leader of the fascist/antisemitic American Bund. In 1939, 20,000 of Kuhn’s followers and sympathizers packed Madison Square Garden for a rally, and Winchell lambasted it as a “vile sacrilege” of American freedom.

Winchell was sensitive to antisemitism, which was openly prevalent in American society before World War II. And he was not afraid of being labelled “too Jewish” by detractors. In this spirit, he attacked the American hero Charles Lindbergh after he delivered a veiled antisemitic speech on behalf of the isolationist American First Committee.

Much to his ultimate detriment, Winchell allied himself with Joseph McCarthy, the red baiting U.S. senator. From that point forward, Winchell was perceived as a right-wing demagogue.

When the African American dancer Josephine Baker was snubbed by waiters at the segregated Stork Club, she lashed out at Winchell, claiming he had not come to her assistance. He vindictively condemned her as a communist, an accusation that effectively wrecked her career.

Winchell tried his hand at television, but it was not a medium to which he would successfully adapt. He was dealt two more blows when his 33-year-old son, Walt Jr., committed suicide, and when he lost his column after the New York Daily Mirror folded in 1962.

Consigned to the ranks of the unemployed, Winchell bought an ad in Variety in which he pathetically pleaded for a job. He died in 1972. Only one person, his daughter, attended his funeral.

Winchell’s star glowed brightly for several decades, but like a meteor, he crashed, extinguishing a career that seemed so limitless.