Ehud Barak, nearing 80 years of age, can look back at a rewarding career in public service.

He was prime minister of Israel from 1999 to 2001. Prior to his ascent to the premiership, he held three cabinet portfolios, having been interior minister, foreign minister and defence minister. Subsequently, he was the leader of the middle-of-the-road Labor Party.

Before entering politics, Barak was chief of staff of the armed forces, holding that position from 1991-1995.

Today, he’s a consultant and apparently doing extremely well.

Earlier this year, Barak agreed to be interviewed by Ran Tal for a film about his career as a soldier and politician. Tal’s documentary, What If? Ehud Barak On War And Peace, will be screened online at the Calgary Jewish Film Festival on November 21 at 7 p.m.

Barak, having grown a scraggly beard in the last few years, sits in a stark studio and answers Tal’s questions. Some are very speculative, revolving around the notion that events might have taken a different turn had this or that happened. The interview is supplemented by newsreels and photographs.

Strangely enough, Tal begins with a question concerning Barak’s plan in 1974 to kill Yasser Arafat, the chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization. “It made perfect sense to me,” he says. “He was our enemy.”

Barak, then an up-and-coming army officer in an elite commando unit, presented his idea to his superiors, but they vetoed it, possibly changing the course of history.

Two decades later, when he was foreign minister, Barak shook hands with his nemesis. The expression of dismay on Barak’s face was proof of his dislike and mistrust of Arafat. Yet when Tal asks Barak whether he would have joined a “terrorist” organization had he been a Palestinian under Israeli occupation, he replies in the affirmative.

At this point, the film abruptly shifts to Barak’s roots as a kibbutznik. Born on Mishmar Hasharon in 1942, he was the son of Polish Jews who arrived in Palestine in the 1930s. He has fond memories of the kibbutz, but observes that his Arab neighbors in nearby villages “vanished” during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. The kibbutz acquired some of their lands, but Barak has no qualms about the displacement of their inhabitants. “We win and get the land,” he says almost flippantly.

Whether Palestinian Arabs were displaced during that war depended on the “temperament” of local Israeli commanders, he believes. Arabs in Lod (Lydda) were expelled, but Arabs in Nazareth were permitted to stay.

Fast-forwarding to the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Barak recalls returning to Israel from his studies at Stanford University in California to join the fighting. Invited to attend a wartime meeting of the army’s general staff, Barak was shocked by the ashen, downcast appearance of the generals. The only general who radiated confidence was David Elazar, the chief of staff, who was later reprimanded by a special commission examining the origins and outcome of the war.

Assigned to the Sinai front, Barak participated in the Battle of the Chinese Farm, which he describes at the most bitter of his life. The smell of burning flesh in the air haunts him still today.

As a commando dressed like a woman, Barak led a raid on April 9, 1973 targeting three top Palestinian leaders in Beirut. He does not regret his role in their assassinations. Nor is he sorry he plotted the assassination of Hezbollah leader Abbas Moussawi in Lebanon in 1992. It was the “right decision,” he notes.

Tal shows a grainy black-and-white video of the moment an Israeli missile struck Moussawi’s car, killing him and his family in a flash of flames and smoke. In retaliation, Hezbollah, aided by Iran, bombed the Israeli embassy in Argentina and the Jewish community center in Buenos Aires, claiming the lives of scores of people.

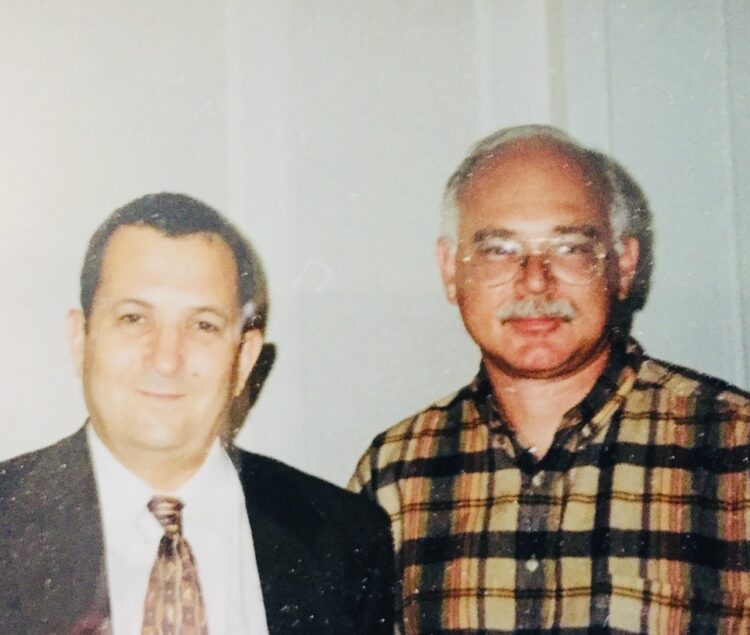

Upon being elected prime minister, Barak had three objectives in mind: peace with Syria, peace with the Palestinians, and the withdrawal of Israeli forces from southern Lebanon. Unfortunately, Tal does not elaborate on any of these major issues. Barak, however, makes a glancing reference to Lebanon. “We were stuck in a vicious cycle,” says Barak, whom I interviewed in 1996 when he was thinking of running for the leadership of the Labor Party.

The film ends on a sour note as Barak discusses the Camp David summit in July 2000. Fearing that Israel and the Palestinians were on a “collision course,” he sought to change the status quo.

The impression he leaves is that the summit, hosted by U.S. President Bill Clinton, foundered due to sharp disagreements over the status of Jerusalem. Saying he was ready to cede partial sovereignty of Arab neighborhoods in eastern Jerusalem to the Palestinian, he claims Arafat was the spoiler because he was unwilling to take historic decisions.

“We failed because we didn’t find a partner,” he says in a stinging critique of Arafat, his longtime foe.

On this note, What If: Ehud Barak On War And Peace comes full circle.