The last three general elections in Israel were marred by widespread accusations that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his Likud Party defamed the Arab community and resorted to inflammatory rhetoric to discredit the Arab Joint List, the third largest party in the 120-seat Knesset. But as Israel copes with the coronavirus crisis, Netanyahu may discover that the Arab Joint List, which represents most Israeli Arab voters, may have a far more important role to play in the formation of Israel’s next government than Netanyahu could ever have imagined.

In the last election on March 2, the Arab Joint List won about 582,000 votes and a record number of 15 seats. Most of its supporters are Muslim and Christian Israeli Arabs, a minority comprising 21 percent of Israel’s population. Nearly two-thirds of eligible Arab voters turned out to vote in the last election, the third since last April, and almost all of them cast their ballots for the Arab Joint List.

A relatively small proportion of its supporters were left-wing Jews, some of whom previously backed the Meretz Party. In Tel Aviv and Jaffa, the Arab Joint List received 11,413 votes from Jews, compared to 8,446 in September. Jews in the Tel Aviv suburbs of Ramat Gan and Givatayim gave the Arab Joint List 573 and 325 votes respectively.

The Arab Joint List, formed in 2015, is an alliance of four parties: the Democratic Front for Peace and Equality, headed by Ayman Odeh; the Arab Movement for Change, led by Ahmad Tibi; the Islamic Movement, which is under the leadership of Abbas Mansour, and Balad, whose leader is Mtanes Shehadeh. These separate parties espouse ideologies ranging from nationalism to Islamism.

The Likud and its allies regard the Arab Joint List as an anti-Zionist party unworthy of inclusion in a coalition government. In Israel’s history, no Arab party has ever formally joined a government. But in 1992, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin required the outside assistance of Arab parties to establish a government.

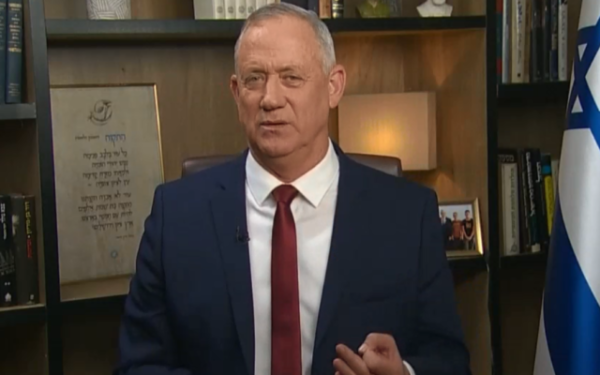

The Likud’s chief adversary, the centrist Blue and White Party, led by Benny Gantz, regards the Arab Joint List ambivalently. Prior to the last election, Gantz discounted the possibility of recruiting it into his centrist/left bloc, saying its values and positions were unacceptable to him and his constituency. Gantz’s associates, Yair Lapid and Moshe Ya’alon, declared that Blue and White would not ally itself with the Arab Joint List and would instead strive to form a “Jewish majority” government.

Gantz modified his view after realizing he might be able to cobble together a government with the support of the Arab Joint List. Under this scenario, Gantz would have the backing of 62 members of parliament, including at least 12 of 15 Arab Joint List parliamentarians. (After the election in September, the Balad faction, which advocates a binational state as a solution to Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians, announced it would not recommend Gantz as the next prime minister).

Stunned by the prospect that Gantz might succeed in forming a government with the help of the Arab Joint List, Netanyahu on March 4 delivered a speech in which he claimed he won this month’s election. Netanyahu justified his assertion on the grounds that his “Zionist-right” bloc had a grand total of 58 seats, compared to 47 for the “Zionist-left” bloc.

Netanyahu omitted the Arab Joint List from his calculation. As he bluntly put it, “The Joint List, which attacks our soldiers and opposes the State of Israel, is not part of the equation.”

In effect, Netanyahu accused its Knesset members of being disloyal, describing them as “terror supporters,” and implied that Israel’s Arab community lacks legitimacy.

It was not the first time Netanyahu had cast aspersions on Israeli Arabs. During the final days of the 2015 election, he urged supporters to vote because Arabs had come out “in droves” to cast their votes.

The incendiary comments Netanyahu has uttered of late have been repeated by his colleagues, adding fuel to the fire.

Foreign Minister Israel Katz denounced Arab Joint List parliamentarians as “terrorists in suits or supporters of terrorists in suits.”

Tourism Minister Yariv Levin said, “The Joint List receives its instructions from Hezbollah.” This may have been a reference to Arab Joint List Member of Knesset Heba Yazbak, who recently praised a terrorist who killed a Jewish family and who expressed support for an Israeli accused of spying for Hezbollah.

Defence Minister Naftali Bennett jumped on the bandwagon, too. As he declared, “An Israeli government dependent on the votes of the Arab Joint List constitutes a clear and present danger to the lives of Israeli citizens and Israeli soldiers.”

According to the U.S. State Department’s annual human rights review, the Likud promoted “hatred” against Israeli Arabs in the first two elections in 2019.

“During the April and September national election campaigns, the Likud Party deployed messages promoting hatred against Arab citizens,” the report said. In the campaign leading up to the April election, the Likud placed cameras in predominantly Arab polling stations “in an effort to dissuade Arab voter turnout,” it added.

On March 6, when Gantz appeared close to forming a government with the silent ascent of Avigdor Liberman of the Israel Beytenu Party and with the explicit backing of the Arab Joint List, he issued an implicit criticism of Netanyahu and the Likud: “We’ll respect all citizens of Israel, whether they chose me or not. Just as I expect the nations of the world to respect the Jewish citizens in their lands, we would never dare say that the votes of 20 percent (of the population) from Israel’s Arab citizens are worth less.”

Responding to Gantz’s dig, Netanyahu on March 7 claimed that he was “evidently ready” to break his vow of not relying on the Arab Joint List “in any circumstance.” The Arab Joint List, he said, “rules out Israel as a Jewish state … and they back a full ‘right of return'” for Palestinians. Denying he is anti-Arab, Netanyahu said that his animus for the Arab Joint List is based on his belief that it “opposes the existence of Israel.”

Netanyahu’s claim is false, since most of its representatives in the Knesset endorse a two-state solution.

Even before Israel was infected by the coronavirus, Gantz’s consideration to coopt the Arab Joint List appeared doomed.

First, Blue and White members Yoaz Hendel and Zvi Hauser announced they could not back a government supported by the Arab Joint List, claiming that its members do not recognize Israel as a Jewish state.

Second, Gesher Party parliamentarian Orly Levy-Abekasis, a member of the left-wing Labor-Gesher-Meretz alliance, said she would refuse to sit in a government supported by the Arab Joint List. Her announcement suggested that Gantz no longer had a sufficient number of seats to form a government, even if all the members of the Arab Joint List backed it.

On March 14, Netanyahu called yet again for an emergency national unity government, urging Gantz, Liberman and Labor Party leader Amir Peretz to join. Significantly, he did not issue an invitation to the Arab Joint List.

Ya’alon has accused Netanyahu of exploiting the outbreak for “personal political needs,” but Gantz, despite his deep reservations about working with a prime minister who has been indicted on three charges of corruption, has expressed a willingness to discuss the idea as long as the Arab Joint List is included.

Netanyahu’s proposal was eclipsed by the news on March 15 that the Arab Joint List would support Gantz as the next prime minister if he rejects his plan for a temporary national unity government. Odeh disclosed that the heretofore recalcitrant Balad faction had fallen into line and would recommend Gantz as Netanyahu’s successor.

If this arrangement works, Gantz would be able to form a majority government with 61 Members of Knesset, which would include Blue and White’s 33 seats, Labor and Meretz’s six seats, Israel Beteynu’s seven seats, and the Arab Joint List’s 15 seats.