October 23 marks the 60th anniversary of the start of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, a nationwide revolt against the Soviet-imposed government of the Hungarian People’s Republic. It lasted until November 10, when it was crushed by Soviet tanks.

At least 30,000 people were killed and some 200,000 others fled to the west.

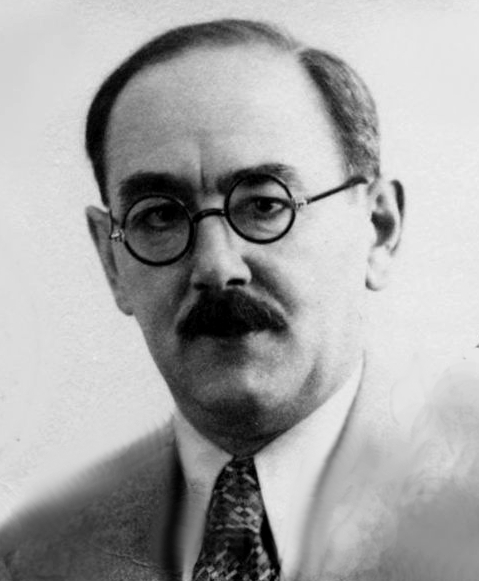

Imre Nagy had been appointed prime minister during this brief window of freedom and announced that Hungary would withdraw from the Soviet-run Warsaw Pact. With the return of Soviet troops and the reintroduction of Communist rule, Nagy was tried, executed, and buried in an unmarked grave.

Even so, the Hungarians were able to define their own more economically liberal brand of Communism. This so-called “Goulash Communism,” instituted in 1968, was formally known as the New Economic Mechanism. When I was in Hungary in 1977, it felt much freer than neighbouring Communist states.

Still, Hungarians longed for a multi-party system, rather than their Soviet-style state. In October 1989, the Communist Party convened its last congress, and the country’s parliament transformed Hungary into a non-Communist republic.

It guaranteed human and civil rights, and created an institutional structure that ensured separation of powers among the judicial, legislative, and executive branches of government.

On March 25, 1990, the first free parliamentary elections in Eastern Europe took place in Hungary. The country seemed to have become a liberal democracy and had joined both NATO and the European Union by 2004.

But things have in recent years taken a different turn, with the rise of Victor Orban and his Federation of Young Democrats–Hungarian Civic Alliance (Fidesz), a nationalist party that has dominated Hungarian politics on the national and local level since its landslide victory in the 2010 national election.

Orban first made his name in Hungary when, as a young lawyer and activist, he spoke at an immense rally in 1989 celebrating the reburial of Imre Nagy. He had helped found his party a year earlier, initially as a youth-oriented liberal anti-communist group.

But under Orban’s guidance, it began to move to the right. The Orban who was elected prime minister in 2010 and re-elected in 2014 had become a political and economic conservative nationalist who promised to restore Hungarian values.

The European refugee crisis of 2015-2016 has brought Orban’s views regarding Hungarian sovereignty into sharp focus. He is a fierce opponent of the EU’s plan to share migrants across the 28-nation bloc under a mandatory quota system.

He has described the arrival of asylum seekers in Europe as “a poison,” saying his country did not want or need them.

“This is why there is no need for a common European migration policy: whoever needs migrants can take them, but don’t force them on us,” Orban stated last July. The populist leader added that “every single migrant poses a public security and terror risk”.

In October, he held a referendum in which 98 percent of participants voted against the admission of refugees to the country. But more than half of the electorate stayed at home, rendering the process constitutionally null and void.

Undaunted, Orban still hopes to lead a “cultural counter-revolution” in Europe, in which liberal ideas like helping refugees are supplanted by identity-based notions of family, community and Christianity, with the EU stripped of its powers to force asylum-seekers onto unwilling countries.

With political freedom has come a renewed sense of Hungarian nationhood, and Orban has tapped into this nationalistic mood. By defending the nation Orban claims to be defending democracy. He even questions its membership in the EU.

Hungarian Jews are alarmed by this, as there are unpleasant precedents to this type of rhetoric.

In the first few decades of the 20th century the Jews of Hungary numbered roughly five percent of the population. Jews were disproportionately represented in the professions and in commerce, relative to their numbers.

But after World War I, the country was ruled by an autocrat, Admiral Miklos Horthy, whose views towards Jews verged on antisemitism.

“I have considered it intolerable that here in Hungary everything, every factory, bank, large fortune, business, theater, press, commerce, etc. should be in Jewish hands, and that the Jew should be the image reflected of Hungary, especially abroad,” he remarked in a letter to one of his prime ministers.

Anti-Jewish laws were passed in the late 1930s, as the country moved closer to Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. Hungary would join the Axis powers in World War II.

Nonetheless, Hungary’s Jews did not become engulfed by the Holocaust until March 1944, when German tanks occupied the country, and the viciously pro-Nazi Arrow Cross Party took power. Of the original 825,000 Jews in the country before the war, about 565,000 perished.

During the Communist period, antisemitism was formally forbidden, though Zionism and mass immigration to Israel were not allowed and contact between Hungarian Jewry and world Jewry were curtailed. But it has now openly re-emerged.

One of the major representatives of current antisemitic ideology is the Movement for a Better Hungary, known as Jobbik, In the election of 2014, the party polled 1,020,476 votes, securing 20.54 percent of the total, making them Hungary’s third largest party in parliament.

In November 2012, Marton Gyongyosi, one of the party’s leaders, posted a video speech on the Jobbik website in which he called for a list to be drawn up of all the Jews in government because he deemed them to pose “a national security risk to Hungary.”

Jewish organizations responded by describing it as a reintroduction of Nazism in Hungary.

In May 2013, Jobbik members protested against a World Jewish Congress meeting in Budapest, claiming the protest was against “a Jewish attempt to buy up Hungary.” Nine months later Tibor Agoston, the deputy chairman of Jobbik’s organization in Debrecen, Hungary’s second largest city, referred to the Holocaust as the “holoscam.”

Jobbik is what is known by political scientists as an “outbidder” party, one that adopts radical strategies to maximize support among voters belonging to an ethnic group. Competition involving ethnic parties often leads to outbidding where parties adopt ever more extreme positions to avoid defeat. Hence Jobbik probably has moved Orban further towards the right.

So today, Hungary’s Jews are fearful again of Hungarian antisemitism.

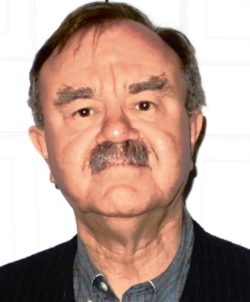

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.