Who is a Russian?

In everyday conversation, people speak of “Russia,” but the country is actually the “Russian Federation.” Even today, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, only 81 percent of its almost 144 million people are ethnic Russians.

So who is a “Russian?” And who is not?

In English, we sometimes differentiate between people’s ethnicity and citizenship, especially when talking about “homeland” nation-states. For instance, we may refer to someone as an “ethnic Hungarian” in Romania, or an “ethnic Croat” who’s a Serbian citizen.

Multinational states often have names that don’t specify any group’s ethnicity. “Soviet” and “Yugoslav” was a state identity; no actual peoples were Soviets or Yugoslavs.

Things get more complex when a multi-national state, such as the Russian Federation, with territorially concentrated peoples, is named after the dominant nation within it.

The country’s political divisions include 22 ethnic republics, where the indigenous ethnic nationality runs its own internal affairs in its own language.

These peoples are citizens of “Russia,” but are not “Russians.” And Russians acknowledge the distinction. The Russian language distinguishes between “ethnic Russian” (“russkiy”) and “citizen of Russia, regardless of nationality” (“rossiiskiy”).

In official, “politically correct” language “rossiiskaia natsiia” is considered the norm. But this is not always the case in everyday speech, where people see Russia in ethnic terms, or even religious ones, in which Orthodox Christianity becomes a component part of Russian identity.

Those who subscribe to an ethnically-based Russian state might seek to annex territories with large ethnic Russian populations, such as some areas of the Baltic states, the northern part of Kazakhstan, or eastern Ukraine; the Crimea has already been absorbed.

At the same time, ethnic nationalists might see the need for Russia to rid itself of certain so-called “undesirable” territories that are currently part of the country, such as the Muslim areas in the north Caucasus.

Even after the dissolution of the USSR, which saw Muslim-majority Azerbaijan and the five central Asian “stans” become independent countries, there are still some 17 million Muslims in the Russian Federation, about 12 percent of the total.

While Russia’s overall population is dropping, the number of Muslims in the country is on the rise. Islam is the second largest religion in the Russian Federation.

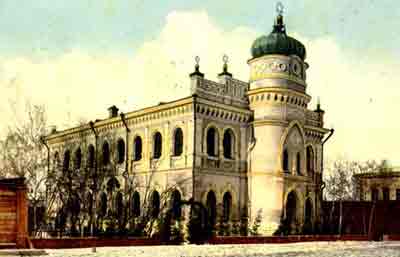

Russia’s Muslims live mainly in two areas: in the Volga region, including the ethnic republics of Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, Udmurtia, Chuvashia, and Mari- El; and in the northern Caucasus, particularly in Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia.

The Crimean Tatars, a Muslim Turkic-speaking people, comprise 15 percent of the peninsula’s population of two million, with the remainder made up of Russians, at 60 percent, and Ukrainians, 25 percent. Many Russians (and Ukrainians) fear the spread of radical Islam among the Tatars.

The Tatars boycotted the March 16 referendum in the Crimea on whether to become part of Russia, and two weeks later their own assembly voted in favor of seeking “ethnic and territorial autonomy” using “political and legal” means. Their status remains uncertain.

The most restive of the numerous Muslim peoples living in the Caucasus, the Chechens, have chafed under Russian domination for 150 years. In the recent past, they have fought two bloody wars, in 1994-1996 and 1999-2000, for independence.

But while the Chechens became embroiled in war with Moscow, the Tatarstan leadership gained much of what they desired without open conflict.

Tatarstan in the 1990s worked out an arrangement with Moscow, formalized by treaty, in which the 3.8 million inhabitants of the republic were acknowledged as having a special relationship with the federal government. Its government considers this to have been recognition by Moscow of the republic’s sovereignty in cultural and economic spheres.

Russia’s Jews, on paper, have a Jewish Autonomous Oblast, or province, in Birobidzhan in the far east, but it contains virtually no Jewish population.

After massive waves of emigration in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, there are probably (numbers are uncertain) no more than 200,000 Jews in Russia, making up a minuscule percentage of the Russian population, and mostly living in large cities such as Moscow and St. Petersburg.

On the other side of the coin, there are some 25 million ethnic Russians living in the so-called “near abroad” — the 14 former union republics of the old USSR, now sovereign states.

Today, Russian minorities range in population from 23.7 percent in Kazakhstan, 25.2 percent in Estonia, all the way to 27.8 percent in Latvia. In war-torn Ukraine, they comprise 17.2 of the country’s people. And most live adjacent to the Russian Federation.

Is Russia to be a nation of Russian citizens (“rossiiskaia natsiia”) or of ethnic Russians (“russkaia natsiia”) only? If the latter, should it also try to incorporate Russian-speaking areas in neighboring states? Because this remains unsettled, there is no consensus on whether Russia’s present-day borders should be accepted as given.

President Vladimir Putin seems to have adopted some central tenets of the nationalist agenda, as is evident in eastern Ukraine, where Donetsk and Luhansk, supported by Moscow, have become virtually de facto states.

Putin has taken to calling much of eastern and southern Ukraine “New Russia,” a historical term referring to territories that were conquered and settled by ethnic Russians beginning in the 18thcentury.

Moscow also continues to demand better treatment of the Russian-speaking minorities in Estonia and Latvia, and some Estonians and Latvians fear that their Russian populations could be potentially manipulated by Putin to destabilise the region.

A civic Russian country, one whose identity is not simply ethnic, can only be a “rossiiskaia” nation. But Russian history is not very encouraging for those who see this as a necessity if the country is to become a modern pluralistic and democratic entity.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.