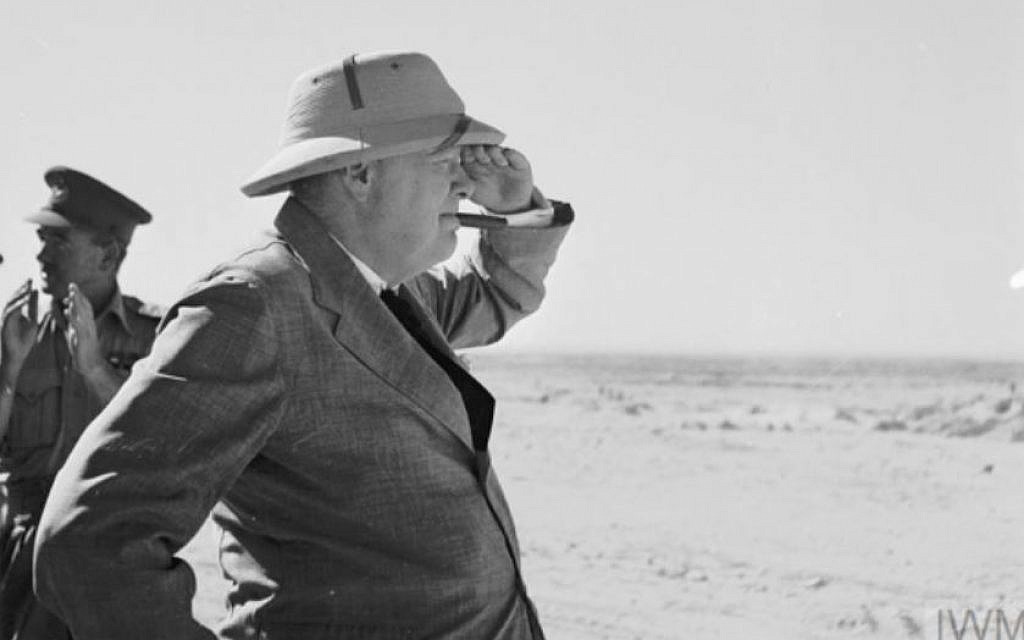

As colonial secretary in British Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s government from 1919 to 1922, Winston Churchill exerted considerable influence in moulding the Middle East.

He was instrumental in laying the foundations of Iraq and Transjordan, the future Hashemite kingdom of Jordan. And in line with the seminal 1917 Balfour Declaration, he supported the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Sara Reguer, a professor of history at Brooklyn College, examines his legacy in Winston S. Churchill and the Shaping of the Middle East, 1919-1922, a wide-ranging account published by Academic Studies Press.

When Churchill assumed his position, the Middle East already had been carved up into European spheres of influences. Among his tasks was to reconcile the contradictory promises Britain had made to Arab nationalists and Zionists and to ensure that Britain’s imperial interests would be preserved.

From 1915 to 1917, British and French diplomats signed a series of secret agreements intended to break up the pro-German Ottoman Empire and to wrest territory from it. Russia and Italy laid claims to Ottoman lands as well.

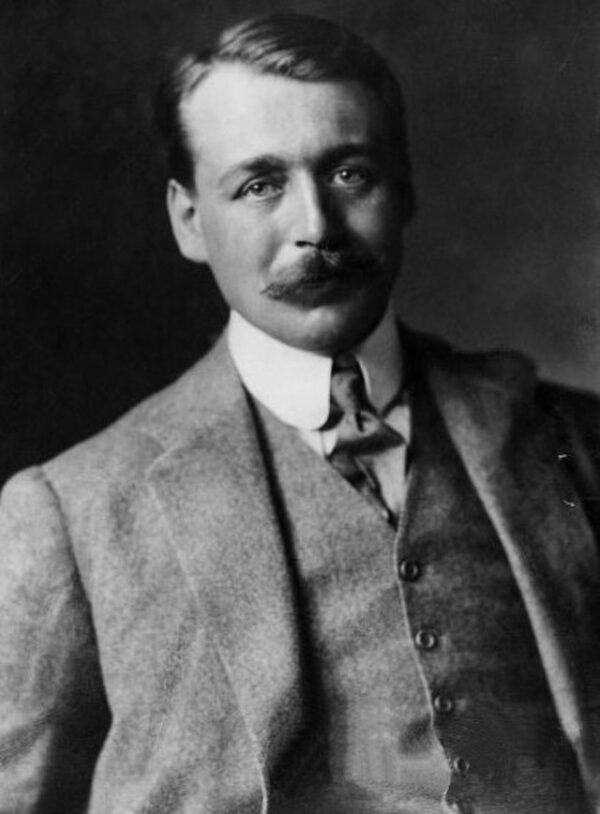

The Sykes-Picot agreement was one of the most important agreements of this period. Signed in 1916 by Sir Marks Sykes, a British Foreign Office advisor on Middle Eastern affairs, and Charles Francois Georges-Picot, a French diplomat in London, it divided Ottoman Arab provinces into five areas comprising present-day Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Palestine.

The Balfour Declaration took the form of a letter British Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour sent to Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild, a wealthy banker and a leading Zionist. It favored the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people on the understanding that nothing would be done to prejudice the rights of its Palestinian Arab inhabitants.

Amid these developments, British expeditionary forces, commanded by General Edmund Allenby and General Stanley Maude, conquered Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq. By 1918, Britain controlled these Arab provinces, and the Ottoman Empire had surrendered.

Two years later, at the San Remo conference, the League of Nations assigned the Palestine and Mesopotamia mandates to Britain and the Syrian and Lebanese mandates to France.

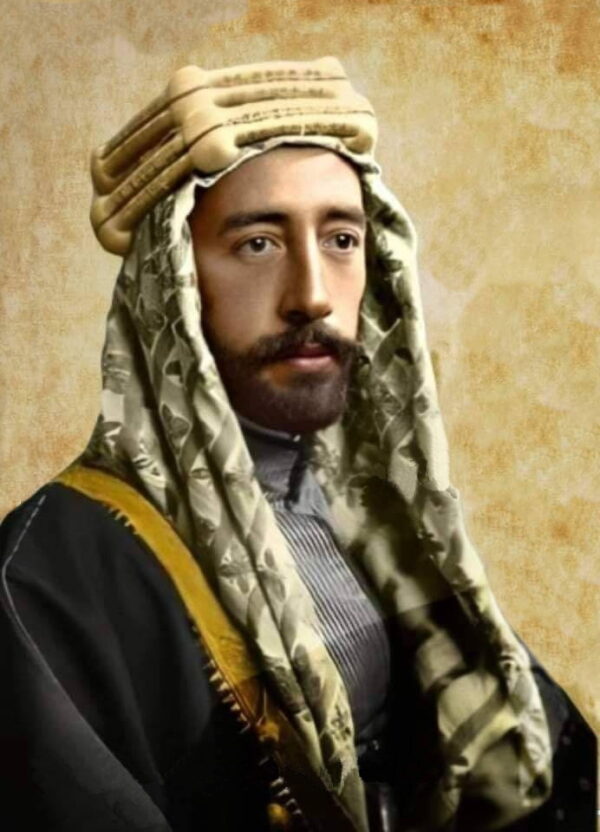

As these events unfolded, Arab nationalists convened a congress in Damascus at which the independence of Syria, including Lebanon and Palestine, was proclaimed. Meanwhile, Faisal and Abdullah, the two sons of Sharif Hussein — the guardian of the Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina — claimed the thrones of Syria and Iraq.

In Turkey, the successor state of the Ottoman Empire, the nationalist Mustafa Kemal Ataturk resisted European military campaigns to annex Turkish territories.

This was the chaotic state of the Middle East when Churchill was appointed colonial secretary.

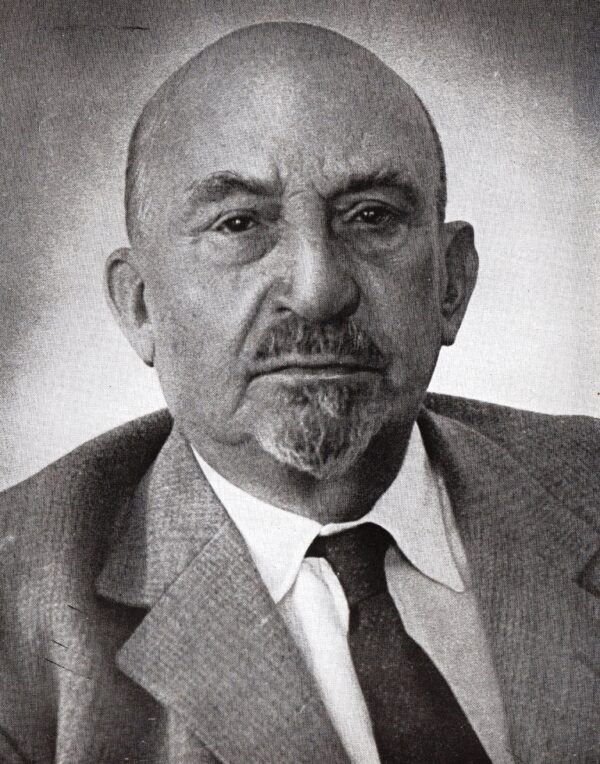

In one of his first decisions, Churchill agreed to separate Palestine from Transjordan, a development that displeased Chaim Weizmann, the head of the World Zionist Organization. He asked Churchill whether western portions of Transjordan could be included in Palestine’s boundaries, but he demurred.

He travelled to Palestine in 1921 to meet Abdullah, the ruler of what would be Transjordan, and representatives of the Jewish and Palestinian Arab communities. “Churchill felt the time had come to clarify his position on Palestine,” writes Reguer.

Abdullah was concerned that Jewish immigration to Palestine might well displace its Arab population. Churchill assured him that it would be a very slow process and that the rights of the Palestinians would be respected.

Palestinian nationalists demanded that he annul Britain’s commitment to the Zionist movement. Churchill replied that its mandate was inextricably bound up with the principle of a Jewish national home in Palestine. He added that Britain had no intention of fostering the formation of a Jewish state. He urged the Palestinian delegation to set aside its grievances and cooperate with the Zionists to create stability and prosperity in Palestine.

Jewish community leaders expressed gratitude to Britain and to Churchill for helping the Zionist cause. As Reguer points out, his sympathies lay with Zionism. A year earlier, in an article he wrote for the Illustrated Sunday Herald, Churchill praised Jews and their contributions to mankind. But Churchill’s endorsement of Zionism hinged on its utility to British strategic interests and on its ability to confer economic benefits to all of Palestine’s population, including the Palestinians.

Prior to leaving Palestine, he attended a reception at the site of the still uncompleted Hebrew University campus on Mount Scopus. He also conferred with Pinchas Rutenberg, an engineer who had applied for a hydro-electric concession harnessing the waters of the Jordan River. And he visited Tel Aviv and the Jewish settlements of Bir Yaakov and Rishon le Zion.

In general, Churchill left Palestine’s affairs in the hands of its first high commissioner, Herbert Samuel, and the Middle East Department of the Foreign Office.

“The major active role that Churchill played was that of defender of the Balfour Declaration,” Reguer says. “There was growing hostility to Zionism in Britain during 1922 and criticism mounted in both houses of Parliament. Churchill’s brilliant speeches … and his written rebuttals succeeded in reaffirming the Balfour Declaration as a basic feature of British policy.”

As for Iraq, Churchill worked to establish a compliant provisional Arab government ruled by King Faisal, whose monarchy would be propped up by Britain and protected by British troops.

Churchill believed that Britain and France should work together in the Middle East. And he insisted that his entire policy in the region was based on a peaceful and lasting settlement with Turkey.

In closing, Reguer argues that Churchill’s policies brought a semblance of peace and development to the Fertile Crescent and Palestine for at least a while. Conversely, as she notes, his patronizing approach to Iraq sowed the seeds of anti-British feeling. In her view, he was partly responsible for creating an “artificial, unviable” state in Transjordan.

For better or worse, Churchill exerted a significant impact on the Middle East.