George Stevens’ Woman of the Year was praised by The New York Times as one of the top ten movies of 1942. Hailing it “triumphant,” the Times‘ critic described it as “a cheering, delightful combination of tongue-tip wit and smooth romance.”

Having just seen it on the Turner Classic Movies channel, I would agree with this gushing assessment.

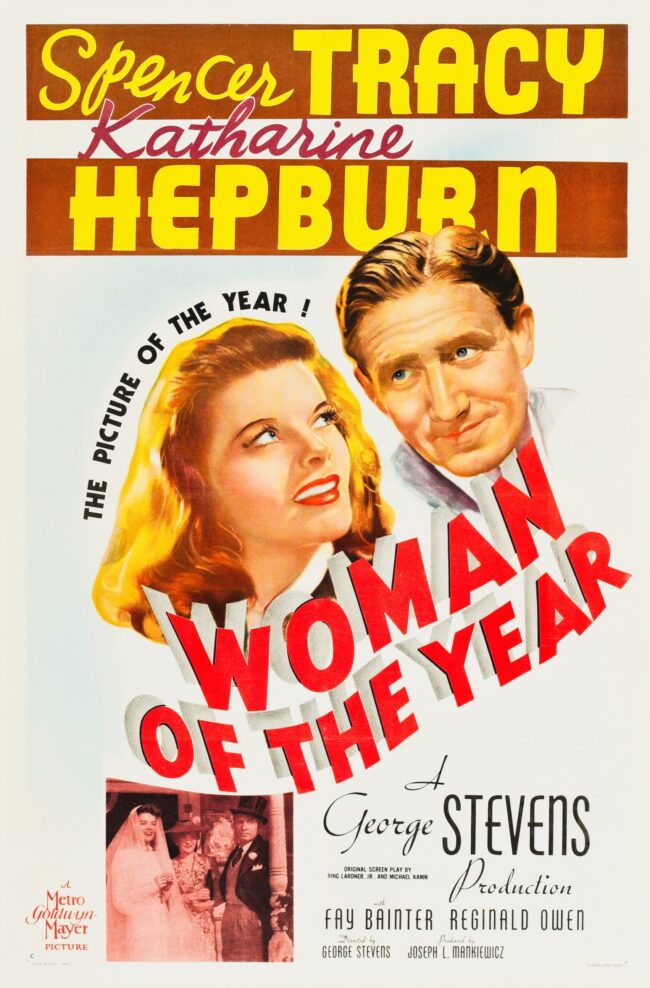

Starring Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy as New York City journalists who fall in love and marry, only two discover they may be temperamentally unsuitable, Woman of the Year was the first of nine films in which they were paired. Their last movie, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, was released shortly before Tracy’s death in 1967.

Hepburn and Tracy are terrific in this sparkling romantic comedy, their chemistry being exactly right. In retrospect, their compatibility was genuine. Although they were both married when they met on set, they fell in love and pursued a 25-year affair.

The dialogue is tart and sizzling. Ring Lardner and Michael Kanin deservedly won an Academy Award for their screenplay. Hepburn, having been nominated for an Oscar in the best actress category, is radiant and alluring. In her first scene, she sexily hitches up her stockings in the editor’s office. Tracy, transfixed by her porcelain beauty, is smitten.

The film was released by MGM in January 1942, a month after the Japanese Air Force bombed the U.S. Pacific naval fleet at Pearl Harbor, prompting the United States to declare war on Japan and enter World War II.

Tracy and Hepburn portray Tess Harding and Sam Craig, both of whom are columnists on The New York Chronicle. Craig covers major league sports and Harding writes about foreign affairs. A newspaper poster on a street promoting Harding’s views reads, “Hitler will lose.” Clearly, she knows her stuff.

As Craig and his ink-stained colleagues sit in a plebeian diner enjoying a meal, they listen to Harding pontificating on a popular radio program. “I really don’t know anything about American sports,” she says in her posh, somewhat pretentious Anglo-American accent. Much to Crag’s dismay, she thinks that baseball, the American national pastime, should be abolished for the duration of the war.

In his next column, Craig chides Harding, and she fires back. Their boss invites the pair for a talk and implores them to “kiss and make up.” They require no further prodding, having fallen head-over-heels for each other. He invites her to a baseball game and she gladly accepts. As she gazes at the crowd in the stadium, she innocently asks, “Are all these people unemployed?”

Harding readily admits she knows nothing about the game. Craig is charmed by her honesty. “You’re wonderful,” he says.

They are polar opposites, of course. Craig is a modest, down-to-earth sort of a guy, an Everyman. His working-class friend, played by the rough-hewn but endearing William Bendix in his first film appearance, is intimidated by Harding. “I read your column all the time, though I don’t understand it,” he admits with a touch of embarrassment.

Harding is indeed formidable. An intellectual and a feminist in an era when most women stayed at home, she is highly educated, exceedingly well travelled and fluent in several European languages. He, self-deprecatingly, remarks that he speaks “broken English.”

They’re both busy people, but her schedule is far more crammed than his. In fact, she needs a secretary to keep track of her appointments, speaking engagements and trips.

Romance blooms at an airport and in the back seat of a taxi cab. After a bout of kissing in her sumptuous Fifth Avenue apartment, she punctures the mood with a off-handed remark: “How about a cold glass of milk?”

When he proposes marriage, she counters, “Are you sure you want me?”

Craig phones his mother to convey the good news. “This long distance call will cost me a week’s salary,” he complains. “Yes, I’ll find out if she’s a good cook.”

At their wedding, her mind is still focused on work. In exasperation, he advises her to drop her bad habits. She does not heed his good advice. On their honeymoon night, she receives a long procession of foreign guests in their bedroom. One of them, a wizened European diplomat, is on the Gestapo’s enemy list.

It seems clear that Craig is playing second fiddle to Harding’s preoccupation with her job. She tries to make amends, but there is no end to the friction tearing up their relationship. Harding is oblivious to her crumbling marriage until she finally grasps the shining truth.

In one of the film’s finest moments, an exemplary model of screwball comedy, Harding attempts to please Craig by cooking one of his favorite dishes. Since she’s a total incompetent in the kitchen, she messes up big time, but he appreciates her goodwill gesture. In the interests of pleasing him, she offers to give up her career and play the role of a submissive housewife.

At the end of the day, Harding’s feminism is only skin deep. As per the values of the times, she is expected to be pregnant, barefoot and in the kitchen. But what can one expect from a traditional 1940s feature film?