For two and a half years, Yemen has been torn by a civil war in which its internationally-recognized government of President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi, backed by a coalition supported by the United States and Britain, is trying to roll back the Iranian-aligned Houthi rebels who control most of northern Yemen, including the capital Sana’a.

The Saudi-led coalition intervened in Yemen in March 2015 and includes Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Jordan, Morocco, Senegal and Sudan.

The Huthis belong to a branch of Shi’a Islam and are allied with supporters of Yemen’s former President Ali Abdullah Saleh. The anti-Huthi forces in the Saudi Arabian-led coalition are mainly Sunni.

Today the country remains split between Houthi-controlled territory in the west and land controlled by the government and its Arab backers in the south and east. Peace talks brokered by the United Nations have stalled, and none of the warring parties has indicated much willingness to back down.

As well, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula controls some of southern Yemen, including areas of Shabwa and Hadhramaut provinces. Earlier this summer, a government offensive in Shabwa, with help from United Arab Emirates and American forces, tried to drive the militants out.

The war against the Houthis has killed more than 12,000 people, displaced more than three million and ruined much of the impoverished country’s infrastructure. Public and private services have all but disappeared, and Yemenis have lost most of their livelihoods and depleted most of their savings.

Repeated bombings have crippled bridges, hospitals and factories. The Saudi-led coalition has also kept the international airport in Sana’a closed to civilian air traffic for more than a year.

The fighting has left 20.7 million people in need of humanitarian assistance, including 10.3 million who require immediate help to save or sustain their lives. More than 17 million people in Yemen, more than half its total population, are currently food-insecure.

On July 2, the World Health Organization reported a cholera outbreak in the country. In just three months, it has killed more than 2,000 people and infected 540,000, one of the world’s largest outbreaks in the past 50 years.

Shortages in medicines and supplies are persistent and widespread and 30,000 health workers, including doctors, have not been paid salaries in nearly a year. There are no doctors left in 49 out of 276 districts.

“Thousands of people are sick, but there are not enough hospitals, not enough medicines, not enough clean water,” stated WHO Director General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

“With the malnutrition we have among children, if they get diarrhea, they are not going to get better,” remarked Meritxell Relano, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) representative in Yemen.

Apart from disease, children are also being killed by the bombing. Human Rights Watch released a study on September 12 documenting the deaths of 26 children killed in five airstrikes since June. The group said that despite promises by the coalition to abide by international law, the airstrikes have failed to do that.

“The Saudi-led coalition’s repeated promises to conduct its air strikes lawfully are not sparing Yemeni children from unlawful attacks,” stated Sarah Leah Whitson, its Middle East director. It called on the UN Security Council to launch an international investigation into the abuses, which may amount to war crimes, at its September session.

“Yemen is a humanitarian disaster of really epic proportions,” added Human Rights Watch Executive Director Kenneth Roth. “What is striking to me is the incongruity between the severity of the disaster and the weakness of the response by the UN Human Rights Council.”

So now UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres is weighing a decision as to whether to include Saudi Arabia in an annual report, called “Children and Armed Conflict,” that lists countries that kill and maim children in war. The Saudis vigorously oppose this.

In a meeting with his top advisors in February, Guterres suggested that the UN delay the release of the report by three to six months to allow the coalition incentive to improve its conduct.

“For me, this was a litmus test,” indicated Eva Smets, the executive director of the Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict. “Is the U.N. going to place human rights first under Guterres?” So far, “it doesn’t look like it.”

Meanwhile, Canada and the Netherlands are spearheading a bid to push a resolution through the UN Human Rights Council this month on creating an International Commission of Inquiry — the UN’s highest-level probe — to investigate abuses in Yemen.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, has urged it to order such a probe into the situation in the country.

This benighted country is no stranger to civil wars involving outside powers.

Back in the 1960s, when the southern part of Yemen was still the British colony of Aden, the north suffered a major conflict between royalist partisans of its Mutawakkilite Kingdom and supporters of the Yemen Arab Republic.

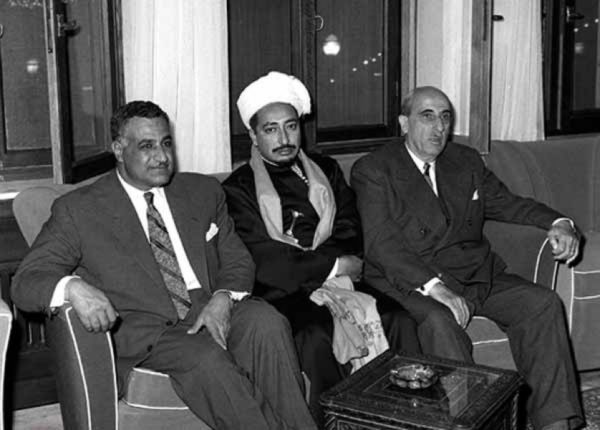

The Egyptian president at the time, Gamal Abdel Nasser, a secular autocrat and champion of pan-Arabism, chose to intervene in Yemen in support of the republican coup, led by military officers who had overthrown the monarchy.

But Saudi Arabia was set against this state of affairs and sought to return Yemen’s ruler, Muhammad Al-Badr, to the throne, and pumped in arms and money to royalist militias.

The war ended in 1970 withthe republicans victorious, but more than 10,000 Egyptian soldiers had died and the country ran up massive war debts. It seems foreigners in Yemen’s internal affairs rarely come out as winners.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.