Chava Rosenfarb was a major twentieth century Yiddish poet and novelist who remains largely unknown outside the tight circle of Yiddish literature.

The lot of a Yiddish writer can be difficult, her daughter, Goldie Morgentaler, suggested at a webinar on November 5 sponsored by the University of Toronto’s Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies and the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

Morgentaler, a professor of 19th century British and American literature at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, has translated her mother’s works into English.

She took questions about her from Miriam Borden — a PhD candidate in Yiddish in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures at the University of Toronto — and from an online audience.

Although her late mother won a succession of literary awards, Morgentaler said she failed to attain the recognition she always sought. Certainly, her eclectic body of work comes nowhere near matching Isaac Bashevis Singer’s fame.

As Morgentaler wrote after her death in 2011, “Despite the great acclaim that her writing has received in the Yiddish-speaking world, Rosenfarb’s work is little known by the non-Yiddish reading public. Her fate as a writer thus reflects the general isolation of Yiddish literature from the mainstream of world literature, an isolation that has unfortunately grown more profound with time.”

A Holocaust survivor from Poland who was profoundly affected by her wartime experiences, she wrote poetry, novels, short stories, essays and plays. According to Morgentaler, she was influenced by Russian, Polish, German and Yiddish writers and poets.

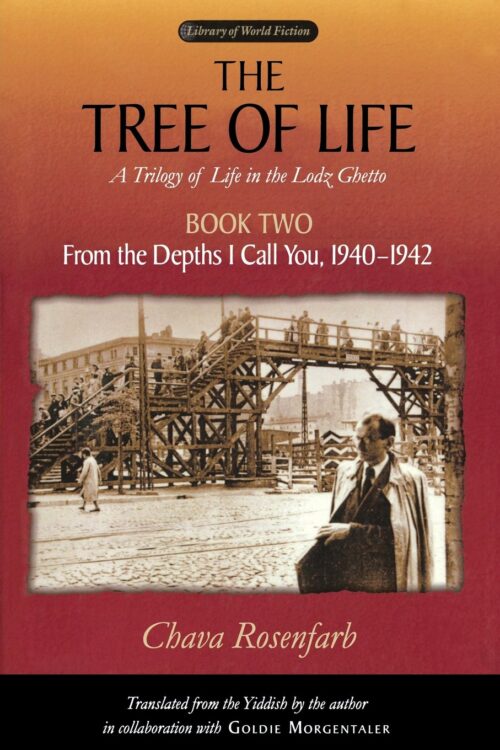

Critics believe her three-volume novel, The Tree of Life: A Trilogy of Life in the Lodz Ghetto, which has been translated into English and Hebrew, was her masterpiece. Chronicling the incremental destruction of the Jewish community in Lodz through the eyes of ten characters from all walks of life, it was the recipient of the Israeli government’s Manger Prize for Yiddish Literature.

Among her other works was the novel, Bociany, published in two volumes; Survivors: Seven Short Stories, and a play, The Bird of the Ghetto, which was performed at the Habimah Theater in Tel Aviv.

She was a contributor to the now-defunct Yiddish journal The Golden Chain, which was edited by the Vilna-born Israeli poet Abraham Sutzkever.

A posthumous selection of her poetry, Exile At Last, was published in English in 2013.

“She was never a scribbler,” said Morgentaler, adding that she began churning out poems at the age of eight. “Writing was her vocation. She had to do it. She couldn’t live without writing. She really had this creative urge.”

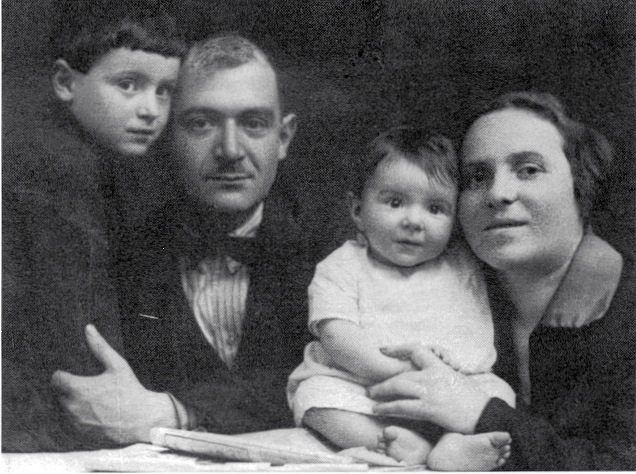

She was born in 1923. Her father, Abraham, was a restaurant waiter, and her mother, Sima, was a textile factory worker. They were both Bundists. She attended a secular Yiddish elementary school and a private Jewish high school where the language of instruction was Polish.

Through her poetry, she met the renowned poet Simcha Bunim Shayevitsch and became his protege. He introduced her to a group of writers in the Nazi ghetto who recognized her talent. She enjoyed the companionship of writers, and for the rest of her life tried to be part of a community of writers, said Morgentaler.

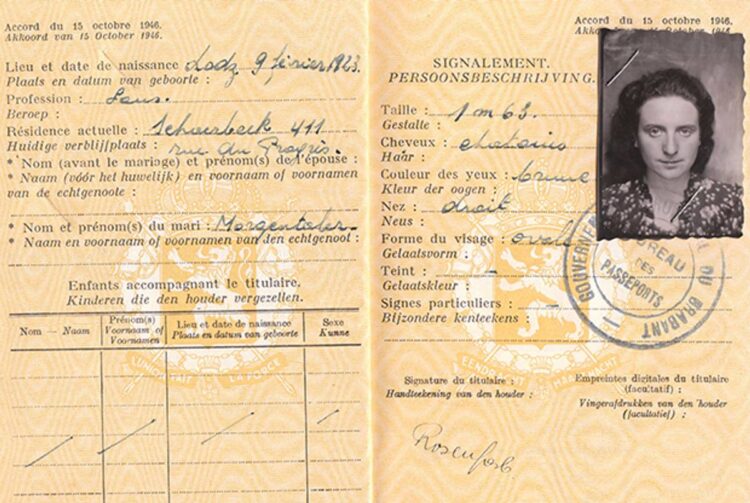

With the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto in August 1944, the Nazis transported the relatively few survivors to Auschwitz-Birkenau. She and her mother and younger sister, Henia, survived the horrendous ordeal. Her father died in 1945, just before the end of World War II. After Auschwitz, the threesome were sent to a labor camp in Germany and the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where she contracted typhus.

During this period, she continued to write poetry.

Asked how Rosenfarb managed to survive, Morgentaler said she was young enough to be resilient. But her survival was also due to “dumb luck,” she noted.

Bergen-Belsen was liberated by the British army on April 15, 1945. One of the soldiers, Douglas Jensen, formed a friendship with Rosenfarb that endured until her death. “It was flirtatious at the beginning,” said Morgentaler. “Where she learned English is a mystery to me.”

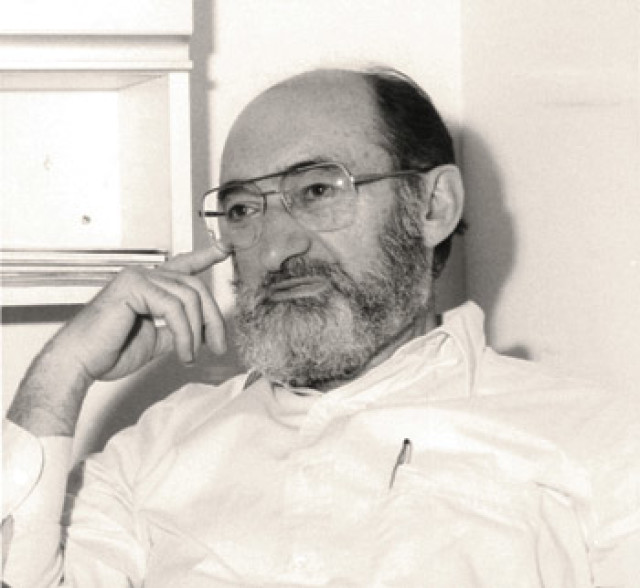

Around this time, she was reunited with her old boyfriend from Poland, Henry Morgentaler, who would become a physician and a celebrated abortion rights activist in Canada. They were married in 1949 and divorced in 1977 after having two children. “My parents didn’t have a good marriage,” said Morgentaler, whose brother, Abraham, is a doctor in the United States.

Years later, Rosenfarb and Jensen, a commercial painter, met again in Britain. At some point, Morgentaler was introduced to him. After he died, she inherited his house.

Rosenfarb and her husband immigrated to Canada in 1950 and, like thousands of Holocaust survivors, settled down in Montreal, where she resumed her writing, which focused on the Shoah. She befriended survivors like herself, but loneliness set in after they passed away.

Eventually, she realized that poetry could not adequately express her deep feelings about the Holocaust. And so she turned to fiction, which enabled her “to go to places she couldn’t go” and to write about people she never personally knew, like the controversial chairman of the Nazi-appointed Lodz Jewish Council, Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski.

As Morgentaler recalls, her mother was self-absorbed. Her preoccupation with writing had a detrimental effect on their relationship. “She was always somewhere else in her mind,” she said.

Yiddish was Morgentaler’s mother tongue, and she attended a Yiddish school in Montreal, yet she was ambivalent about Yiddish. But after Rosenfarb asked her for help in translating The Tree of Life into English, she returned to her Yiddish roots.

Their collaboration, though fruitful, was stormy. “We fought a lot,” she said, referring to their disagreements over such vital matters as diction and syntax. “She could be very stubborn.”

Rosenfarb moved to Toronto in 1998. Several years later, she joined Morgentaler in Lethbridge, where she died.

Morgentaler is thinking of writing a biography of her mother and hoping to publish her letters in book form. In the meantime, she is busy translating her last novel into English.

In the past few years, she has donated Rosenfarb’s archival material to the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto. She is surprised that the Jewish Public Library in Montreal did not even express an interest in it.