Certain events are ineluctably embedded in one’s mind, even after the passage of time and the dimming of memories.

I vividly remember John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the outbreak of the Six Day War and the Yom Kippur War, Anwar Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem, the fall of the Berlin wall, Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, and the destruction of the Twin Towers in Manhattan.

Twenty five years on, I recall the unsettling day when Israel’s prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, was fatally shot by an assassin in Tel Aviv. On November 4, 1995, following a joyous peace rally in the center of the city, he was struck by three bullets fired by a Jewish extremist.

I was dumbfounded when I heard the news flash on the radio, and it fell on me to break it to our Israeli friends visiting us in Toronto. They could hardly believe that Rabin had been gunned down and was forever gone. They were as shocked and distressed as most Israelis.

Aryeh, one of the visitors, went into the kitchen slowly and sat on the edge of a chair, his face pale with sorrow. As he gazed across the room silently, tears rolled down his cheeks.

It was truly an awful moment in Israel’s often turbulent history.

Rabin, whom I interviewed in the early 1990s, was a son of Israel’s founding generation and a leader of the left-of-center Labor Party. Reserved and taciturn, he was a warrior, diplomat and politician.

A soldier in two Arab-Israeli wars and the chief of staff of the armed forces, he was Israel’s ambassador to the United States and prime minister after his predecessor, Golda Meir, resigned. He was then minister of defence in a national unity government and prime minister yet again the wake of a general election.

A product of the Zionist labor movement, he was not a classic peacenik, but a realist who believed that Israel could best assure its security by coming to terms with its Arab neighbors and the Palestinians. To Rabin, Iran posed the greatest existential threat to Israel.

He tried to forge an accord with Syria, one of Israel’s strongest foes, but failed. However, he and his foreign minister, Shimon Peres, reached an agreement with one of Israel’s chief enemies, the PLO, the chairman of which was Yasser Arafat. And so the Oslo peace process was born.

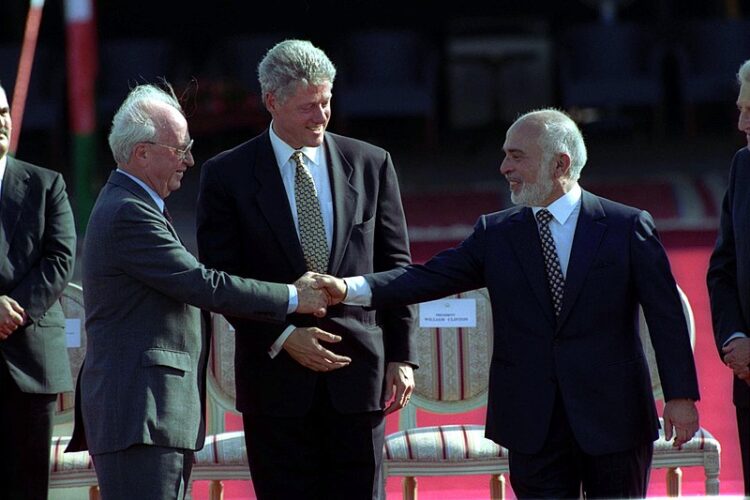

A year later, Israel signed a peace treaty with Jordan, with which Israel shared its longest border. While it was almost universally applauded by Israelis, Israel’s rapprochement with the PLO was bitterly denounced by the right-wing Likud Party and its allies from the national-religious camp, both of which opposed territorial compromise. The Likud’s leader, Benjamin Netanyahu, led the charge in attacking Rabin’s conciliatory position.

Rabin did not speak of Palestinian statehood, but of Palestinian self-determination in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, where Israel had built a network of settlements since the 1967 Six Day War. Nonetheless, Netanyahu lambasted Rabin, while Jewish settlers from the occupied areas compared him to a Nazi and assailed him as a traitor who deserved nothing less than death. Netanyahu attended a demonstration in Jerusalem at which threats were levelled against Rabin’s life.

During this period, Palestinian terrorists, drawn mainly from Hamas, launched a series of unprecedented suicide attacks in Israel, killing scores of Israelis. These assaults hardened Israeli public opinion and soured the prospects for peace.

A far-right Jewish nationalist who railed against Rabin’s accommodation with the PLO was Yigal Amir, a student at Bar-Ilan University. He thought that if he killed Rabin, the Oslo peace process would crumble.

Amir, who was convicted of murder and has been serving a life sentence since his trial, was more or less correct. Rabin’s successor, Peres, was narrowly defeated by Netanyahu in the 1996 election. Under U.S. pressure, Netanyahu reluctantly resumed negotiations with the Palestinians, but he was opposed to territorial concessions and Palestinian statehood.

Netanyahu lost the 1999 election to Ehud Barak, the Labor Party leader and an ex-general who had commanded the armed forces. Unlike Netanyahu, Barak believed in the promise of Oslo, but he fell short of reaching a comprehensive agreement with Arafat at the 2000 Camp David summit, which was sponsored by U.S. President Bill Clinton.

This failure proved to be disastrous. Within two months, the second Palestinian uprising broke out, setting off a spate of Palestinian terrorism and Israeli reprisals which effectively buried what was left of Oslo.

The deep divisions that pitted conservatives against liberals over the land-for-peace formula during the Oslo era still scar Israel’s political landscape.

Israelis are as divided today as they were 25 years ago, though greater numbers of Israelis are skeptical that peace with the Palestinians is possible.

Netanyahu’s indictment on charges of fraud, breach of trust and bribery, together with the widespread perception that he has mishandled the response to the coronavirus pandemic, have widened the yawning gap between Israelis who love and hate him. This has led to further polarization.

His supporters are convinced that he was framed and that he has performed well in containing the contagion. Netanyahu’s detractors are confident that he is guilty as charged, that he poses a threat to democracy, and that he failed to competently deal with the plague, which already has claimed the lives of more than 2,500 Israelis

In the past few weeks, Israelis who detest Netanyahu have mounted protests demanding his resignation. Some of Netanyahu’s followers have gotten into fisticuffs with demonstrators and thrown stones and fired pepper spray and tear gas at them. In a few cases, Netanyahu’s backers have attempted to run them over with cars and trucks.

The majority of anti-Netanyahu protesters are in the peace camp. They are willing to consider territorial compromise in the West Bank in the interests of achieving a workable arrangement with the leadership of the Palestinian Authority.

“The air is suffused with combustible flames, just waiting for someone to throw a match,” one Israeli commentator wrote ominously.

The bitter and divisive mood that currently grips Israel reminds observers of the rancorous climate that prevailed on the eve of Rabin’s assassination.

Netanyahu, who has been accused of having played a role in the campaign of incitement against Rabin, told a special Knesset session to mark the anniversary of his death that the atmosphere is still volatile and that he, personally, faces threats.

“Twenty five years after the murder of Rabin, there is incitement to assassinate the prime minister and his family, and almost nobody says anything,” he said, condemning political violence and “the destructive effects of incitement.”

As for Amir, he remains unrepentant. Never having expressed regret, he remains wedded to his belief that he had no alternative but to kill Rabin in order to throttle the peace process and preserve Israel’s occupation of the West Bank.

Amir filed a request to be furloughed from prison so that he and his wife, Larissa could celebrate their son’s bar mitzvah. He was conceived in Amir’s cell during a conjugal visit. The request was denied by the Israel Prisons Service last week and by a magistrate court in Beersheba on November 4.

Since Israeli intelligence agencies regard Amir as a threat to Israel’s national security, he will likely spend the rest of his life behind bars.