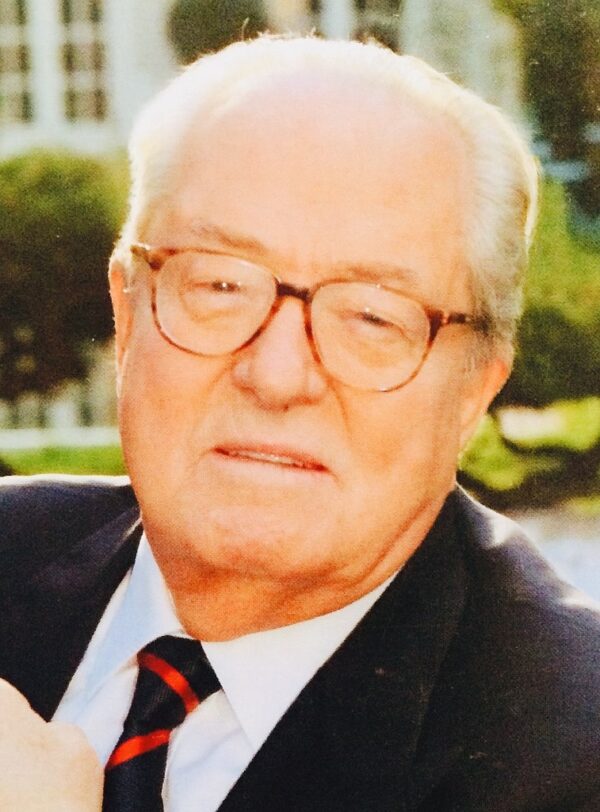

Eric Zemmour, a journalist who belongs to no political party and has never held public office, is running as an outsider for the presidency of France.

Zemmour, 63, is a highly unusual candidate — a Jew who has embraced the politics of the far-right.

A defender of Christian civilization who compares himself to Donald Trump, he’s a proponent of the white supremacist conspiracy theory that whites are being “replaced” by Arab Muslims and black Africans, who, he fears, are systematically invading and colonizing France.

Twice convicted and fined of inciting racial hatred, he believes that France has fallen into a state of decline, and that only he can lead it out of the doldrums and restore it to its glorious past.

“It is no longer time to reform France, but to save it,” he has said.

Zemmour has warned that the France of “Joan of Arc and of Notre-Dame and village churches is disappearing.”

An iconoclast who has tapped into the grievances of a fair proportion of the electorate, he is generally supported by men, older people and the upper middle-class.

He opposes virtually everything the elite has embraced, including multiculturalism, internationalism and environmentalism. If elected, he says, he would virtually end legal immigration, deport illegal migrants, and demand that parents give their children traditional French names.

Claiming that Islam is at odds with France’s core values, he has promised to close mosques operated by the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists. Zemmour says he entered politics so that “our daughters don’t have to wear headscarves and our sons don’t have to be submissive.”

Opponents have accused him of racism and of pursuing an xenophobic agenda. What is clear is that he is attempting to outflank Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right National Rally Party, on issues like immigration and national identity.

In recent years, Le Pen has distanced herself from her father, Jean-Marie, whose legacy is permeated with antisemitism. Two days ago, she laid a wreath at a monument in Warsaw honoring the Jewish fighters of the 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising.

Tellingly enough, Jean-Marie Le Pen has endorsed Zemmour. In an interview with the Le Monde newspaper, he said, “The only difference between Eric and myself is that he is Jewish.” Le Pen suggested that Zemmour’s background is an advantage because critics will be hard-pressed to accuse him of being a Nazi or a fascist.

Zemmour’s foreign policy is unconventional. He refers to the United States, France’s oldest ally, as “the most dangerous country in the world.” And he regards the NATO alliance as obsolete and an instrument of American imperialism. He seeks closer relations with Russia.

Formerly employed by Le Figaro, a conservative daily published in Paris, Zemmour has disseminated his ideas through his best-selling books and frequent appearances on television. His latest book, France Has Not Said Its Last Word, has sold 250,000 copies since its release in September.

Zemmour’s forays into French Jewish history have been controversial, to say the least.

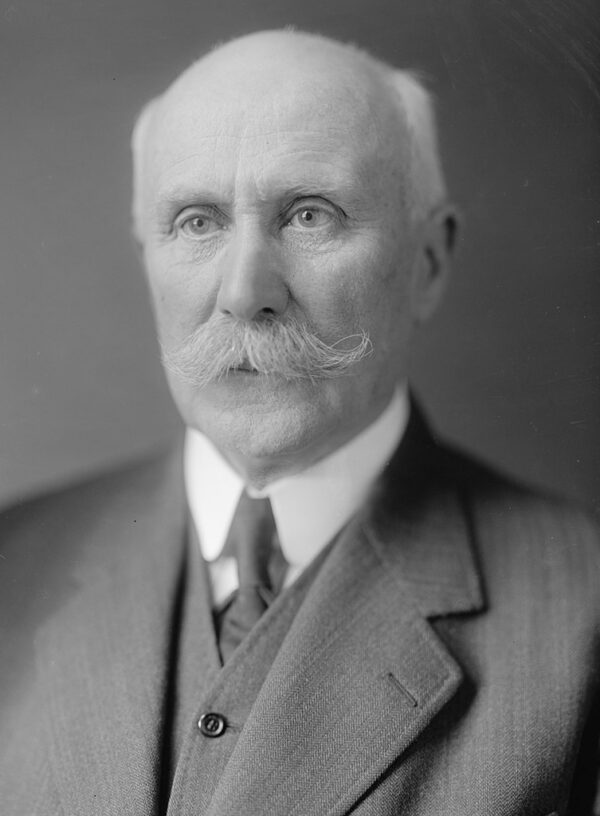

He has cast doubt on the innocence of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer whom antisemites accused of being a German spy. The Dreyfus affair, which divided France along ideological lines, was a cause célèbre in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Having been found guilty of treason, Dreyfus endured humiliation, disgrace and imprisonment on Devil’s Island. Having been exonerated, he was restored to his rank.

Zemmour, however, is not convinced that Dreyfus was innocent. “We will never know,” he said recently, defying the historical record.

Zemmour has also aroused indignation with his fallacious claim that Henri Philippe Petain, the collaborationist leader of Vichy France — an ally of Nazi Germany which passed sweeping antisemitic legislation in 1940 — persecuted foreign-born Jews so that native-born Jews could be saved from deportation.

This is an outright lie.

In fact, one-third of the Jewish citizens of France were deported to their deaths in Nazi extermination camps in Poland. The rest were subjected to a panoply of harsh restrictions and treated with the utmost severity.

Zemmour’s attitude to the murder of five French Jews killed by an Arab terrorist in a Jewish school in Toulouse in 2012 was bizarre. He claimed they were not really “French” because they were buried in Israel. “They were foreigners,” he said flippantly.

Such cavalier and insensitive comments have offended most Jews.

Recently, the chief rabbi of France, Haim Korsia, denounced Zemmour as an antisemite. The philosopher Bernard Henri Levy has dismissed him as a “traitor par excellence.” In a stinging rebuke, the historian Simon Epstein wrote, “He flits easily from truth to untruth, with a clear predisposition towards exaggeration and falsity.”

It is clear that Zemmour is abusing and mangling history for his own selfish ends.

At present, polls have placed Zemmour in third place, with about 15 percent of the electorate supporting him. He is running behind President Emmanuel Macron, a centrist, and Le Pen, but the situation is fluid and could change before next April’s election.