Eero Saarinen passed away five decades ago, but his architectural legacy remains firm and strong. “He figured out a way to be important across time, so even though he died young, he is still alive,” says his son, Eric, who takes us on a journey of his father’s works in Eero Saarinen: The Architect Who Saw the Future.

Scheduled to be broadcast on the PBS network on Tuesday, December 27 at 8 p.m. as part of its American Masters series (check local listings), this bracing documentary by Peter Rosen is both a biopic and an appreciation of his stellar contribution to architecture.

A modernist whose buildings, monuments and furniture were astonishingly visionary, he designed national historic landmarks such as the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan, the TWA Flight Center at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York, and the Dulles Airport in Virginia.

Saarinen’s place in the pantheon of American architecture is analysed by a procession of experts — the architects Robert Stern, Kevin Roche, Cesar Pelli and Rafael Vinoly, the industrial designer Niels Diffrient, the critic Paul Goldberger, the curator Donald Albrecht, the author Jayne Merkel and the editor of Architectural Record, Cathleen McGuigan.

The son of Eliel Saarinen, an eminent Finnish architect who immigrated to the United States in 1922, he was raised in an ambience that inspired him to follow in his father’s footsteps. Indeed, he joined his firm after graduating from Yale University.

As the film suggests, Saarinen established his reputation with one of his first commissions — the Gateway Arch, an expression of American optimism and openness which gave him the strength of character to pursue his professional dreams.

Proceeding from the assumption that architecture “fulfills man’s belief in the nobility of his existence,” Saarinen honed his remarkable skills in a variety of projects: TWA’s Flight Center, which conjured up the drama and excitement of travel; Dulles Airport, whose curvaceous lines were futuristic, and the Miller house in Columbus, Indiana, one of his rare private residences.

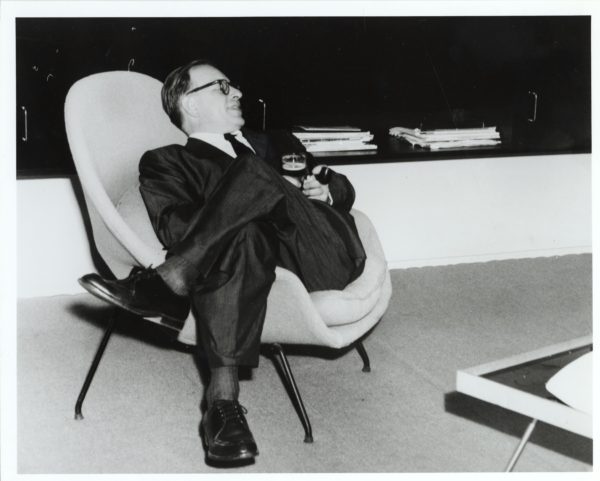

He also designed modernist furniture, which looks very contemporary today.

As architecture was his “great love,” Saarinen devoted body and mind to it. “Work was the most important thing for him,” says his son. “It wasn’t the money.”

Due to his heavy work load, he neglected his first wife — a sculptor, artist and educator — as well as his son. On a promotional trip, he fell in love with an art critic of The New York Times, Aline Bernstein Loucheim, and left his family for her. Their letters to each other sizzle with romance and passion.

She promoted him assiduously and convinced Time magazine to place him on one of its covers. After Saarinen’s untimely death in 1961, she ensured that all his buildings were finished.

Saarinen’s style was not universally admired, as the film acknowledges. But he was certainly one of the greatest architects of our time.