David Kirshner, my loud, lively, gregarious, boisterous and unforgettable father, departed from this vale of tears in the early hours of January 20 as I slept soundly.

The shattering news was conveyed to me, in the dead of winter, by my younger sister, Shirley, whose frantic message awoke me with a start. I was thus burdened with the unpleasant task of telling Marilyn, my elder sister on vacation in Florida, of his passing.

David’s penultimate day began when Shirley, his primary caregiver, took him to the hospital after he had started vomiting. “Don’t leave me alone,” he had said, thinking she might forsake him. He need not have worried. Shirley, a devoted daughter, remained at his side, doing everything in her power to comfort and console him.

David was no stranger to the health care system, having been taken to the hospital several times in the past 10 years. He had always returned in fine fettle, but this time, he did not return to his beloved wife — my mother Genya — and three children.

David, 101, died of cardiac arrest a few months shy of his 102nd birthday, a courageous fighter to the end.

David, or Dawid Kirszner, as he was known in Poland, was born in Lodz on April 10, 1914. Throughout his life, he dealt with adversity, but David had a penchant for self-preservation. As a soldier in the Polish army, he survived the German invasion that sparked World War II. As a civilian, he survived the Holocaust, an armed robbery, kidney cancer, two hip replacements and a heart implant.

He was a remarkable survivor, a “traditional Polish Jew,” as my oldest friend, Henry Srebrnik, wrote, and a member of a doomed Polish Jewish generation.

Battle-scarred and physically spent, David was laid to rest on January 22 on a gentle hill bathed in faint sunlight. His death saddened me, but I was grateful for the extremely long, useful and worthwhile life he had been bequeathed.

A man who bestrode the 20th century and the first years of the present century, he lived through the unfolding panorama of history — World War I, the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, the resurrection of Poland, the emergence of communism in Russia and fascism in Italy, the rise of Nazism and state-sponsored antisemitism in Germany, the virtual destruction of the Jewish community in Poland, the birth and development of Israel, the rise of Arab nationalism, Iran and Islamic State, the invention of the television and the computer, and the triumph of the Internet and the smart phone.

David was privy to the unimaginable depths to which human beings can so easily descend, yet he was blessed, having been granted a reprieve of 72 years. How so? While nearly all his contemporaries in Lodz were brutally killed during the war, he scraped through by the skin of his teeth, happy to have outlived his enemies.

A master tailor by trade, he was called up for duty by the Polish army. When the Germans invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, he was attached to the 27th Infantry Regiment. David served in field commands in Truskolasy, Czestochowa, Janow, Olsztyn and Lelow.

Badly wounded in the leg by shrapnel, he was captured and treated for his injuries in a German military hospital in Czestochowa. Transported to a German prisoner-of-war camp in Konradsheim, he was then sent to the Lodz ghetto in February 1940. I surmise he survived because he was a fireman in the ghetto — the last one to be liquidated by the Nazis. Firemen were considered essential workers, and so he was spared.

If he had been a laborer in one of the workshops which churned out goods for German soldiers and civilians, he might have perished. But maybe not. Ever resourceful, David had great survival instincts and knew how to take care of himself and his two sisters, Rushka and Helen. But to his everlasting regret, he could not save his parents or brother from the jaws of death.

With the dismantlement of the ghetto in August 1944, David was sent to a succession of Nazi concentration camps, including Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. I think he survived this unspeakable ordeal because of his unsurpassed skills as a tailor and his will to live. He often told me a story about a German colonel who saved him because he had “adopted” him as his personal tailor.

When the war ended, David was one of the relatively few Jews still left in Lodz. He and Genya soon found themselves in a displaced persons camp in southern Germany, where I was born in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps. In 1948, we arrived by train in Montreal for a fresh start. David, a family man, was a hard worker and a good provider, though my mother had to go to work, in a bakery, for the extras we required.

The Holocaust, of course, left an indelible imprint on David.

As he grew older, he constantly rehashed this cataclysmic event, describing his experiences in a mixture of Yiddish and English and rattling off the names of familiar Nazi villains like Hitler, Himmler and Goring. With bravado, he claimed he would have finished them off with his bare hands had he been given the chance.

I listened quietly, asking questions, but occasionally, I grew weary of his grim preoccupation with the dark and unspeakable past and his tendency, in later years at least, to blur the line between reality and fantasy. He also devoured picture albums and newspaper stories about the Holocaust, marking off sentences and paragraphs in his large and distinctive European script. On some days, he was fond of showing off the Polish war medals on his blue blazer.

Despite his obsession with the Holocaust, he never seriously considered a trip to Poland, which I visited several times as his surrogate. He would carefully examine the photographs I had taken and the postcards, books and mementos I had bought or acquired in his native land.

When I arrived at my parents’ condo in Toronto, David would be sitting at the kitchen table, slowly consuming a breakfast of porridge or oatmeal that had been prepared for him by Zeny, one of his caregivers.

In general, David was a fussy eater, but he liked simple Polish peasant fare like rye bread, boiled potatoes and cabbage, soups, pickled or schmaltz herring, pressed cottage cheese and pickles. His favorite dessert was my mother’s apple cake. Much to her consternation, he did not care for meat dishes.

Having finished his interminable meal, he would retire to a padded pink chair in the living room and wait for Thomas, the health care worker who generally arrived at 11 a.m. to help him with his daily shower.

Various ailments rendered him frail after the age of about 95, but thankfully, David was mentally engaged and alert. He had subscriptions to the The Toronto Star and the Canadian Jewish News, and in typical fashion, he underlined or circled articles that particularly interested him. I confess I inherited this habit from him.

David was especially drawn to crime stories and breaking news about Israel and the Middle East. He remembered much of what he had read and heard on television. No detail was too small for him. He could, for example, recall the population of Iran, an arcane statistic embedded in his fount of knowledge.

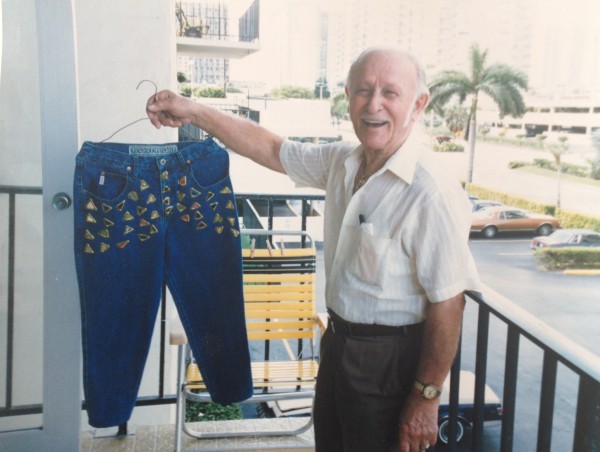

My parents retreated to their condo in Florida from December to April every year. David did not adore the sun, nor did he appreciate the beach, so he was not really a snowbird in the classic sense of the word. Instead, for several years, he sought out part-time employment in a dry cleaning store close to his home away from home.

When he was still fairly mobile, David liked going to the Promenade Mall. He’d talk to total strangers, who were never less than bemused by his direct and guileless manner. And then he would look up acquaintances in the food court before settling down for a cup of coffee or chocolate ice cream in a cup or cone.

A dandy in his prime, David groomed himself immaculately, spending what seemed like hours in front of the bathroom mirror, shaving, parting his hair and applying talcum powder to his face.

“I’m handsome and gorgeous,” he would say facetiously.

Quick to bouts of sustained laughter, David was an extrovert by nature, a character, if you will. Yet he kept important thoughts to himself.

These jumbled thoughts raced through my mind as I slipped a hand-written note into David’s wooden casket before it was sealed for eternity.

I wrote: Go in peace and tranquility, and stay strong and true to yourself.

David is gone now and will be terribly missed, but if you take a leisurely walk down memory lane, he’ll always be there, alive and well and laughing uproariously, a compelling and larger-than-life figure who will never die.