Five years on, the Arab Spring has turned to winter, its bright hopes dashed in all but Tunisia, and the Arab world is worse off than ever.

Egypt has come full circle, once again chafing under an authoritarian-military dictatorship, while Libya, Syria and Yemen have fared even worse, descending into chaos and civil war.

On January 25, 2011, following the ouster of Tunisian strongman Zine El Abidine Ben Ali eleven days earlier, demonstrations erupted against Egypt’s long-serving autocrat, Hosni Mubarak. On February 11, he stepped down from the presidency after three decades, forced to give way to the massive protests that had raged throughout the country, and in particular, in Cairo’s Tahrir Square.

But now the anniversary of that event has been marked by sullen resignation. For the few who turned up to observe the occasion, chanting “Down with the tyrant!” against President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, they faced thousands of police officers patrolling the streets of Cairo and public squares.

In advance of the anniversary, a crackdown by security forces saw activists rounded up, art houses closed and the administrators of opposition Facebook pages detained. “The security and stability of nations are not to be toyed with,” Sisi had warned Egyptians in a speech.

Sisi had led the military in ousting Mubarak’s Islamist successor, Mohammed Morsi, in 2013 following mass protests, a year after the Muslim Brotherhood leader had become the country’s first democratically elected head of state.

After his overthrow, Morsi faced several charges, including inciting the killing of opponents, espionage, and terrorism, and was sentenced to death, along with other defendants, last May. The sentence is being appealed.

Meanwhile, Sisi had himself been elected president in 2014. Since he came to power, more than 1,000 people have been killed and 40,000 are believed to have been jailed in a sweeping crackdown on dissent.

Most of them have been supporters of the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood, but secular activists have also been prosecuted. Meanwhile, Mubarak and his cronies, not to mention the police responsible for killing hundreds in the clashes of 2011, are out of jail.

Local and international human rights activists say the situation in the country has never been worse. Amnesty International has stated that Egypt is now “mired in a human rights crisis of huge proportions” as the country “reverts back to a police state.”

Sisi’s new constitution grants sweeping powers to the president and the army, while “peaceful protesters, politicians and journalists have borne the brunt of a ruthless campaign against legitimate dissent by the government and state security forces,” according to Said Boumedouha, Amnesty’s deputy Middle East and North Africa director.

Syria has descended into an abyss of butchery, and has become the battleground for proxy wars involving Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Lebanon’s Hezbollah, and even Russia and the United States. President Bashar al-Assad hangs on to power while at least 250,000 Syrians have been killed and millions more have fled the country.

Pro-democracy protests had erupted in March 2011 in the southern city of Deraa after the arrest and torture of some teenagers who painted revolutionary slogans on a school wall.

This triggered nationwide protests demanding Assad’s resignation. The government’s use of force to crush the dissent led to armed rebellion. Fighting had reached the capital, Damascus, and the city of Aleppo, by 2012.

The war acquired sectarian overtones, pitting the country’s Sunni Muslim majority against the president’s Shia Alawite sect.

Today, Sunni Islamic State fighters have taken control of huge swathes of territory across northern and eastern Syria, establishing a “capital” in Raqqa. Meanwhile, attempts by outside parties, including Moscow and Washington, to broker an end to the war have so far failed to stem the violence.

Elsewhere, Libya and Yemen have imploded, their central states replaced in whole or part by warring militias, some backed by foreign powers, some flying the flags of al-Qaeda or the Islamic State.

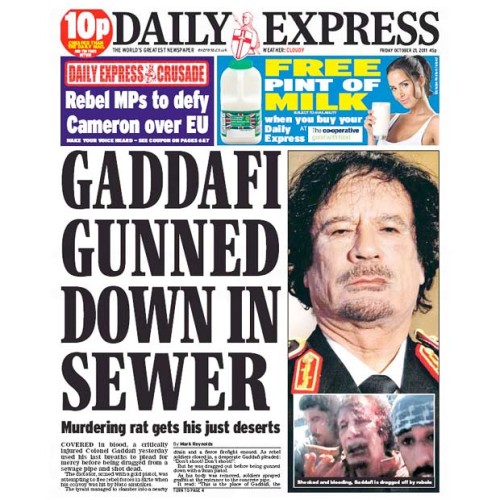

The demise of Libya’s quixotic but ruthless dictator, Moammar Gadhafi in October 2011, left a political vacuum in the country that has been filled by rival militias, Islamist followers pledging allegiance to the Islamic State, and rival governments.

Two administrations have been competing for control of Libya since mid-2014: the internationally recognized government based in Tobruk in the east, and the unofficial Government of National Salvation based in the capital, Tripoli. Each has its own parliament and a host of militias fighting on its behalf.

The creation of a unity government, the culmination of a year-long process of United Nations-sponsored negotiations between representatives of the rival administrations, was announced on Dec. 17, but it has now fallen afoul of quarrels between the two camps.

The Islamic State’s followers have created their own base in Sirte, Gadhafi’s former home, and several other towns. They have carried out a number of strikes against the country’s oil infrastructure.

Yemen, too, goes from bad to worse.

The nine-month war between Yemen’s Houthi rebels, who belong to the Zaidi Shia sect and are backed by Iran, and the government of President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, supported by a Saudi-led military coalition that has been conducting an aerial campaign against the rebels since March, shows no signs of abating.

The conflict has left some 6,000 people dead in what was already the Arab world’s poorest state.

Hadi had assumed the presidency on February 27, 2012, replacing the autocratic Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had ruled the country since 1990 (and had previously served as president of North Yemen for 12 years). Saleh was forced out after months of massive protests in Sanaa, the capital, and elsewhere.

Pledging to support efforts to rebuild the country reeling from months of violence, Hadi however soon found himself running a failed state that shows little sign of recovery.

The region’s governments remain among the most corrupt on the planet. Respect for the rights of women and minorities has deteriorated since the Arab Spring catapulted Islamist forces to power. Poverty remains widespread, and opportunity for economic advancement is non-existent for huge proportions of unusually young populations.

The hopes raised by the Arab Spring for people who were hoping for more inclusive politics and more responsive government have been dashed.

The big winner in all of this has been Iran, which has taken advantage of the turmoil in the Arab world to strengthen its alliances with Shiites in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.