Israel is, technically, not the only official Jewish homeland in the world. Hidden away in the far east of Russian Siberia, 8,361 kilometres east of Moscow, and not that far from the Pacific Ocean, is the Jewish Autonomous Region (JAR) of Birobidzhan.

And it’s even bigger than the far more famous Jewish state: Birobidzhan has an area of 36,300 square kilometres, larger than Holland and Belgium combined, as opposed to Israel’s pre‑1967 20,770 square kilometres.

How and why was Birobidzhan set aside as an area for Jewish settlement? It was founded in 1928, 20 years before the establishment of Israel, the result of Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin’s nationality policy, which stated that each of the national groups that formed the Soviet Union would receive a territory in which to pursue cultural autonomy in a socialist framework.

The idea was to create a new Soviet Zion, where a proletarian Jewish culture could be developed. Yiddish, rather than Hebrew, would be the national language, and a new socialist literature and arts would replace religion as the primary expression of culture.

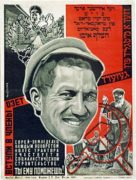

By the mid‑1930s a massive propaganda campaign was underway to induce Jewish settlers to move there. Some of these efforts incorporated the standard Soviet propaganda tools of the era, and included Yiddish‑language posters and novels describing a socialist utopia.

As the Jewish population grew, so did the impact of Yiddish culture on the region. A Yiddish newspaper, the Birobidzhaner Shtern, was established; a theater troupe was created; and streets in the new capital city were named after prominent Yiddish authors such as Sholem Aleichem and Y. L. Peretz.

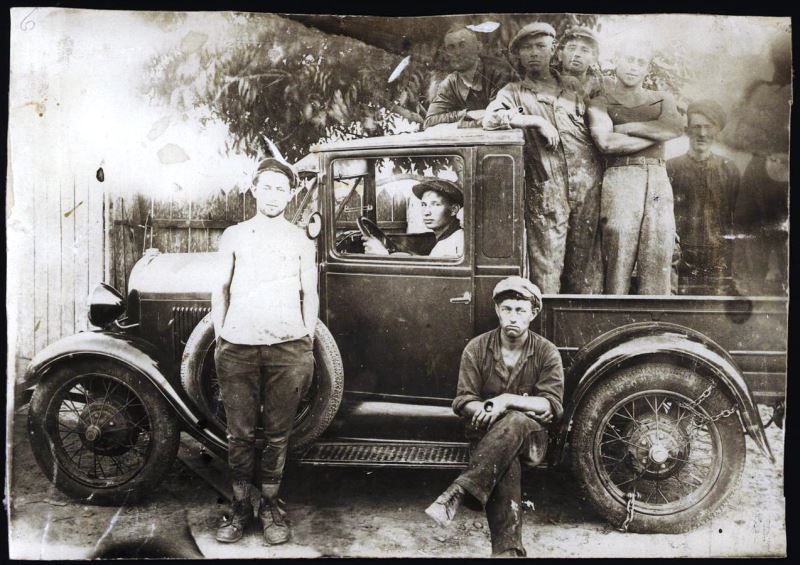

Posters from the 1930s resemble Zionist literature from the same era, exhorting Diaspora Jewry to help build a Jewish land in Russia. The propaganda impact was so effective that several thousand Jews immigrated to Birobidzhan from outside of the Soviet Union in the 1930s.

Most of Birobidzhan lies between the 48th and 49th parallels north latitude, and a 1929 commission compared it, topographically, to Ontario and Michigan. Indeed, the fact-finding team was headed by Franklin S. Harris, an American agronomist who had lived on a ranch in Alberta where, he said, “the climate and conditions were similar to Birobidzhan.”

During that time, the Jewish population of the region peaked at almost one‑third of the total: some 41,000 Jews had relocated to Birobidzhan. But with the 1948 establishment of Israel as a Jewish state, and Joseph Stalin’s wave of antisemitic purges, the idea of an autonomous Jewish region in the Soviet Union would all be but forgotten. Birobidzhan, in any case, lacked the moving symbolism that Eretz Israel offered, and most Soviet Jews did not want to participate in the secular Jewish nation that the Soviet state offered them.

Stalin moved to wipe out all traces of Jewish culture in the region. He closed Yiddish schools, theaters and synagogues. He forbade the practice of Judaism, and the speaking of Hebrew or Yiddish. Birobidzhan stagnated and was all but forgotten, even by pro‑Soviet sympathizers.

When the USSR collapsed in 1991, Jews made up just two percent of the total population of about 190,000. The rest were ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Koreans, Chinese and various indigenous peoples.

But there has been a revival of Jewish life in the post‑Communist JAR. At the central train station a sign proclaims “Birobidzhan” in both Russian and Yiddish. Yiddish is once again taught in the schools, the Birobidzhaner Shtern is again published, and there is Yiddish radio and television. A new Jewish community centre and synagogue have been built and a Sholem Aleichem monument unveiled.

A Birobidzhan Jewish National University has been founded and in 2007, a Birobidzhan International Summer Program for Yiddish Language and Culture was launched by Yiddish studies professor Boris Kotlerman of Bar-Ilan University in Israel. Birobidzhan’s Chief Rabbi Mordechai Sheiner, a Lubavitcher chasid, has stated that “Jewish life is reviving, both in quantity and quality.”

The city of Birobidzhan is the administrative, economic, and cultural center. According to many who visit, it is a tidy, well‑kept municipality of some 75,000 residents. Its wide, recently paved boulevards and green, tree‑lined streets bear witness to the relative economic prosperity currently enjoyed by the entire Russian Far East.

The JAR, with a population of 176,000 today, most of them ethnic Russians, has well‑developed industrial and agricultural sectors and its rich mineral and building and finishing material resources are in great demand. Non-ferrous metallurgy, engineering, metalworking, and the building material, forest, woodworking, light, and food industries are the most highly developed industrial sectors. The main crops are corn, buckwheat, soybeans, and melons, followed by vegetables. Cattle and poultry are raised on the rich grasslands, and an abundance of nectar‑producing plants creates favorable conditions for beekeeping.

The Amur River, which separates Birobidzhan from Chinese Manchuria to its south, connects the region to the Pacific Ocean. Other rivers include the Bira, Bidzhan, Birakan, Urmi, and Ikura. The Trans‑Siberian Railway passes through the JAR, linking it with Russia and countries in east Asia and the Pacific. There is increased trade with China across the Amur River.

Of course Birobidzhan never came even close to rivaling the Jewish state in Israel. Today,the Jewish population of the JAR is about 4,000, according to Jewish community figures. Over 15,000 former residents and their descendants now live in Israel, about a third of them in the town of Ma’alot, Birobidzhan’s sister city.

The community, while it still survives, is really just a living footnote to history and another far‑flung outpost of the Diaspora.

Henry Srebrnik is a political science professor at the University of Prince Edward Island.