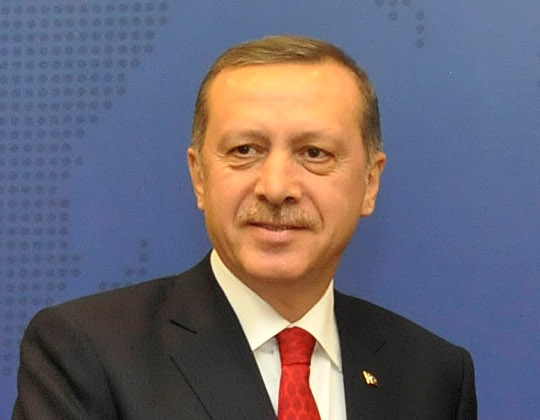

Israel’s important but mercurial relationship with Turkey has entered a promising era after years of mutual acrimony, yet Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a harsh critic of Israeli policy toward the Palestinians and a supporter of Hamas, continues to criticize Israel, sometimes quite stridently.

Israel and Turkey — the only Muslim member of the NATO alliance — restored full diplomatic relations last June after a rupture of six years. Israel’s new ambassador to Turkey, Eitan Naeh, presented his credentials to Erdogan on December 5, hailing the “new phase” in their relations.

Turkey’s incoming envoy to Israel, Mekin Mustafa Kemal Okem, arrived in Tel Aviv a few days ago and handed his letter of credence to President Reuven Rivlin in a ceremony in Jerusalem on December 12. Okem, a confidant of Erdogan, said, “This is a new beginning in our bilateral relations and in our joint efforts in this region in which we have close ties, historical ties.”

Before these developments unfolded, there were already signs on the horizon that Israel’s relations with Turkey had improved.

In October, Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz met his Turkish counterpart, Berat Albayrak, in Istanbul to open discussions on the possibility of building a gas pipeline from Israel to Turkey. At least six years had elapsed since a meeting between Israeli and Turkish ministers had taken place.

About a month later, Turkey dispatched fire-fighting planes to help Israel extinguish wildfires in the Galilee.

There is no doubt that the restoration of full Israeli relations with Turkey, a move encouraged by the United States, places Israel in an advantageous position. Israel can now try to resurrect an entente that was torn asunder by a bloody clash on the high seas in May 2010.

Turkey angrily withdrew its ambassador in Tel Aviv following an incident in the Mediterranean Sea during which Israeli commandos boarded the Mavi Marmara, a Turkish vessel en route to deliver humanitarian supplies to the Gaza Strip.

The ship, leased by the Istanbul-based Humanitarian Relief Foundation, was part of a flotilla of vessels attempting to break the Israeli naval blockade of Gaza, which has been controlled by Hamas, Israel’s bitter foe, since 2007.

Nine of its passengers, eight Turkish nationals and an ethnic Turkish U.S. citizen, were killed during the melee. A 10th Turk died of his wounds several years later.

The violent confrontation, which caused injuries to 10 Israeli soldiers, prompted Turkey to recall its ambassador in Israel, cancel military cooperation programs with Israel and order the Israeli ambassador in Ankara to leave the country.

In short order, Turkey demanded an official apology from Israel, compensation for lives lost and an end to Israel’s siege of Gaza.

Talks between Israeli and Turkish diplomats got under way in various European capitals shortly afterwards to address these demands. There was little progress in the negotiations until U.S. President Barack Obama intervened in 2013. But it was not until this past summer that the impasse was finally broken.

Israel, having issued an apology in 2013 at Obama’s request, sweetened the deal by agreeing to pay a lump sum of $20 million to the victim’s families, ease the siege of Gaza and allow Turkey to send supplies to Gaza via the Israeli port of Ashdod.

On June 30, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu praised the rapprochement. As he said, “We are returning to full normalization with Turkey. Our vital interests are advanced by this agreement.”

Turkey’s deputy prime minister, Mehmet Simsek, was just as upbeat. “The reconciliation agreement with Israel is good for Turkey and the entire region,” he said in August shortly after the Turkish parliament voted to approve it.

Before the Mavi Marmara affair, Israel and Turkey were close allies, though contentious differences over the resolution of the Arab-Israeli conflict generated tensions.

Israel’s invasion of Gaza in 2009, for example, angered Erdogan, an Islamist whose supporters tend to be anti-Israel. In a rage, he described Israel’s military operation as “state terrorism.”

There were other incidents which cast a pall over Israel’s bilateral relations with Turkey, but for Turkey, the Mavi Marmara affair was the final straw.

Now that it’s finally been settled, and a Turkish arrest warrant against four Israeli senior commanders involved in the raid has been rescinded, Israel and Turkey can move forward.

The warrant in question was directed at Gadi Ashkenazi, the former chief of staff of the armed forces; Eliezer Marom, the former commander of the navy; Amos Yadlin, the former head of military intelligence, and Avishai Levy, the former chief of air force intelligence.

Turkish prosecutors, having held them criminally responsible for the deaths of the Turks aboard the Mavi Marmara, had been seeking life sentences for their involvement. But on December 9, a court in Istanbul dropped the case, clearing the Israelis of any liability.

Despite the improvement in Israel’s relations with Turkey, Erdogan shows no signs of moderating his critical stance toward Israel.

On November 21, in his first interview with an Israeli journalist in more than a decade, he dismissed the idea that the commandos had tried to avert bloodshed when they stormed the Mavi Marmara. “It is impossible that the soldiers were acting in self-defence,” he claimed. “We have all the documents and evidence.”

During the course of the interview, Erdogan also blamed the Israeli government for the collapse of peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority in 2014, and asserted that Hamas — “a refugee movement born out of nationalism” — must be a party to any future peace accord.

Erdogan, however, walked back his claim that Israel’s incursion into Gaza in 2014 was comparable to barbaric Nazi crimes. As he put it, “I don’t agree with what Hitler did and I also don’t agree with what Israel did in Gaza. ”

On November 29, on the 69th anniversary of the United Nations Palestine partition plan, Erdogan declared, “Policies of oppression, deportation and discrimination have been increasingly continuing against our Palestinian brothers since 1948.”

As well, Erdogan accused Israel of attempting to change the status quo at the Al Aqsa mosque in the Temple Mount compound in eastern Jerusalem. “Jerusalem is holy to three religions,” he said in a reference to Judaism, Islam and Christianity. “You have to respect that.”

Erdogan unloosed these critiques despite Israel’s obvious annoyance with him.

During the third week of August, Turkey’s foreign ministry condemned Israel after the Israeli air force struck Gaza. Israel launched these strikes after a Palestinian bombardment of the border town of Sderot.

Responding in kind to Turkey’s condemnation, Israel’s foreign ministry issued a press release: “The normalization of our relations with Turkey does not mean that we will remain silent … Israel will continue to defend its civilians from all rocket fire on our territory, in accordance with international law and our conscience.”

Judging from this testy exchange, it seems clear that while Israel and Turkey have embarked on the process of normalization, they will not hesitate to criticize each other.

At the end of the day, Israel expects reciprocity from Turkey.

As Netanyahu said on December 11 while condemning the Kurdish bombings in Istanbul that claimed the lives of 44 Turks, “Israel condemns all terrorism in Turkey and expects that Turkey will condemn all terrorist attacks in Israel. The fight against terrorism must be mutual. It must be mutual in condemnation and in countermeasures, and this is what the state of Israel expects from all countries it is in contact with, including Turkey.”

It remains to be seen whether Turkey will abide by Israel’s demand.