Agata Tuszynska, an eminent Polish poet and cultural historian, found out she was Jewish at the age of 19. Until that moment, she had never met a Jew, nor had she ever concerned herself with the history of Polish Jews. To her, Jews were as exotic as native American Indians or ancient Egyptians.

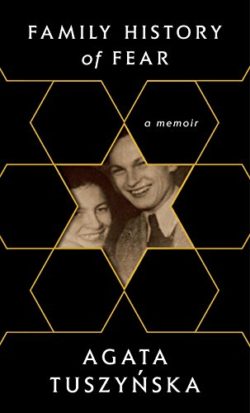

Having been apprised of her Jewish origins by her mother, she kept the information to herself. “I considered her secret as a humiliation and a disfiguring feature, something it is appropriate to be ashamed of,” she writes in an affecting memoir, Family History of Fear (Alfred A. Knopf). “Otherwise, she would never have hidden it from me.”

Tuszynska’s reaction was instructive. In a country whose pre-World War II Jewish population of 3.3 million was almost entirely decimated during the Holocaust, and where open manifestations of antisemitism are not that uncommon even today, a very small minority of Jews have taken the easy way out and masqueraded as Christians so as to avoid problems for themselves and their children.

Halina Przedborska-Tuszynska, her mother, was one of those Jews who abandoned her faith. A Holocaust survivor in Nazi-occupied Poland who was eight years old when the war broke out, she converted to Roman Catholicism in 1947.

“She had no wish to look behind her, or inside either, where there was only fear and shame,” her daughter writes. “Her new fate — Polish, Aryan, orderly, clear — could not be tainted by dread; that is, by being Jewish. That had to stay a secret.”

Halina and her Catholic husband, Bogdan Tuszynski, met in the autumn of 1950 when they were both university students aspiring to be journalists. They were married in 1955. He would become a sports reporter for Polish Radio whose assignments took him around the world. She would be a feature writer for the daily Zycie Warszawy.

Theirs was not a happy marriage. Bogdan would go off on antisemitic tirades despite or because of Halina’s Jewish antecedents. His outbursts never bothered her, but the couple separated when Tuszynska was a youngster.

Raised as a Catholic, Tuszynska was oblivious of her Jewish heritage, as she explains in this revealing passage: “I was in my second year in high school when one of my classmates … delivered a glowing report in our civics class, praising Hitler for having resolved the Jewish problem. He said that Hitler had purified Poland of its Jewish scurvy, something many had tried to pull off before the war without success. The teacher made no objection. I did not understand what he was talking about.”

Her next paragraph is written in the same vein: “I did not understand why Mama broke down and sobbed during a film about the Warsaw ghetto. There was no calming her. I knew practically nothing about the Jewish quarter in Warsaw.”

Looking back at her mother’s decision to apprise her of her Jewish descent, Tuszynska observes: “I had blue eyes and blond hair, a source of great pride to my mother, whose own eyes and hair were dark. Today, I realize she wanted a Polish child, for fear of the fate her daughter might inherit otherwise, a fate like her own. And although the war was officially part of the past in a new socialist Poland, where everyone was equal by definition, she resolved to obscure her origins.”

In short, Halina wanted Agata to be a Polish child weighed down neither by stigma nor burden. “In her estimation, one could always broach the subject when a child was capable of handling it and taking care of herself.”

Tuszynska writes about this sensitive topic with honesty and grace. She uses the same stylistic technique in the chapters about her mother’s Jewish family.

Their home town, Leczyca, was bombed by the German Air Force on September 3, 1939, three days after Germany invaded Poland. Ten days later, the Germans marched into the town. In 1940, they set the synagogue on fire. And in the winter of 1941, they created a ghetto for its Jewish inhabitants. Tuszynska goes on to explain how members of her family survived the Holocaust.

Being assimilationists, they melted into mainstream society in post-war Poland. “Assimilated Jews did not call themselves Jews,” she writes. “They didn’t use the term, as if it were embarrassing or shameful. And when others defined them that way, they felt as if they were victims of denunciation.”

She adds, “They felt wounded and degraded when someone from the outside, a stranger, a Pole, Polish people, pointed them out as Jews.”

Writing of the 1967-1968 state-sanctioned antisemitic campaign in Poland, Tuszynska says that assimilated Jews were generally surprised by it and unable to defend themselves.

As for her mother, she behaved as if nothing had happened. “She decided that (it) did not concern her,” Tuszynska says.

In closing, she asks, “Am I permitted to judge? Mother wanted to be Polish. Completely, as soon as the war ended. She avoided situations that put her in need of defining herself. If she had to, she always selected Polishness.”

The reader may wonder where she stands with respect to her own identity. “I do not want to choose only one heritage,” says Tuszynska, who divides her time between Warsaw, Paris and Toronto. “Both of them — the Polish and the Jewish — are alive in me. Both make me what I am. Even if they oppose one another and accuse each other — I belong to both. And let it remain that way.”