Beijing, China’s capital, is monumental in scale and scope.

A city of broad avenues, bustling traffic and quaint shops, with a population of 12 million and counting, its historic sights run the gamut from the Forbidden City and the Ming Tombs to the Summer Palace and the Temple of Heaven.

And the Great Wall of China is just a short drive away.

The Forbidden City, commonly referred to here as the Palace Museum, is a world heritage site and probably Beijing’s premiere attraction. The imperial residence of two dynasties, the Mings and the Qings, it was closed to the public for 500 years until 1925. Even today, some of its buildings remain off-limits to tourists.

Considered China’s biggest and best-preserved ensemble of medieval buildings and statuary, it’s surrounded by a moat and lies in a garden-like setting of 72 hectares.

The vast complex is divided into two sections: the outer court, which served as an administrative center where the emperor received officials and foreign dignitaries, and the inner court, which was the domain of the emperor, his family, his concubines and his retinue of servants.

From the Hall of Mental Cultivation to the Palace of Earthly Tranquility, the buildings are painted mainly in red and yellow, the traditional colors of the royal family.

The brass statues of scowling dragons, growling tortoises and graceful cranes, which were utilized as giant incense burners, leave an impression of strength, confidence, fear and power. A huge bronze vat, placed in front of the Hall of Great Harmony, still bears the scratch marks left by an Anglo-French army that ransacked the grounds in the 19th century, when China was divided and weak.

Yu Hua Yuan, the expansive imperial gardens, is filled with flower beds and rockeries and dotted with stately pines and cypresses.

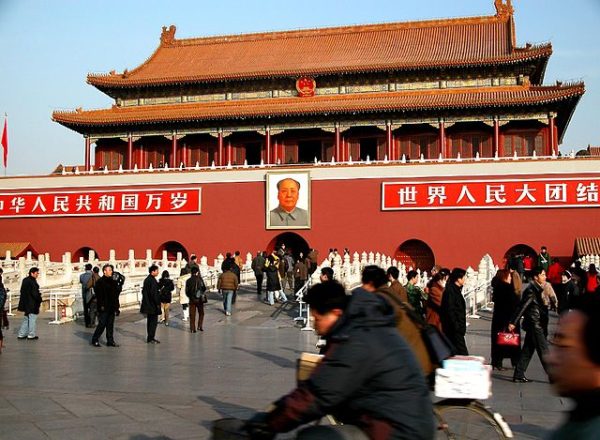

Next to the Forbidden City is Tiananmen Square, which can accommodate one million visitors when important events take place. At one end is a gigantic portrait of Mao Zedong, who proclaimed the People’s Republic of China in October 1949.

The square is ringed by a medley of grand buildings, from the Great Hall of the People to the Museum of the Chinese Revolution. Souvenir hawkers pester tourists and Chinese boys fly kites.

The most prominent structure in the square is Mao’s grandiose mausoleum, where he rests in a sarcophagus. I lined up in a long queue to catch a fleeting glimpse of Mao, and after about 20 minutes, I was ushered into a dim room. There he lay in repose, his waxen features looking unreal.

A sign warned: Be quiet and do not talk.

Not a word was heard as visitors filed past the illuminated corpse, its cheeks dimpled and its dyed black hair neatly combed. In death, Mao reminded me of Lenin’s surreal preserved corpse in Moscow’s Red Square.

I was funnelled into a gift shop carrying an array of cheap Mao memorabilia and trinkets. What would Mao have thought of the crass commercialism?

The Summer Palace, in one of Beijing’s northern suburbs, strikes a completely different tone. Set on tranquil Kunming Lake, it’s a magnificent outdoor museum of classical Chinese architecture and gardens.

From the Hall of Benevolence to the Hall of Jade Ripples, the buildings exude grandeur and elegance. Perhaps the single most impressive sight is The Long Corridor. Seven hundred or so meters in length, it’s decorated with some 8,000 lively paintings inspired by Chinese folktales, novels and landscapes.

The palace, originally built in 1750, is a reminder of the subjugation China once endured at the hands of Western imperial powers. Razed by marauding French and British soldiers in 1860, the palace was rebuilt six years later, only to be ravaged again in 1900. Following the 1949 communist revolution, it was renovated yet again.

The Temple of Heaven, enclosed in a park in Beijing’s Chongwen district, is about 600 years old. Its most outstanding building, the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, stands out in bold face. Covered with glazed blue, green and yellow tiles symbolizing heaven, earth and morality, it’s 38 meters high and 24 metres in diameter.

The Ming Tombs, found at the foot of Mount Tianshoushan, contain the remains of 13 emperors and burial objects. The tombs, dating back to the early 15th century, are reached via the Sacred Way, a paved path flanked by mature weeping willow trees and a stately procession of Ming officials, warriors and beasts cast in marble.

The fast-disappearing hutongs, or narrow streets formed by traditional courtyard residences, are another tangible expression of Beijing’s past. At the rate Beijing is expanding, most of the remaining hutongs may soon be gone, a relic of a distant era.

I wandered around Liulichang Street, whose stores sell Chinese antiques, paintings, arts and crafts, calligraphy, curios, stationary and second-hand books.

Wangfujing, one of Beijing’s busiest shopping streets, is the polar opposite of Liulichang, a cluster of brightly-lit name-brand shops, modern malls and smoky kebob stalls redolent of China’s far western Muslim provinces.

The Great Wall, a bulwark against invading armies and the only man-made object visible from space, runs 6,350 kilometers across northern China. It was constructed over the course of 2,000 years beginning in 221 BC.

The most intact section, in Badaling, is close to Beijing. It’s an imposing structure. From its ramparts and parapets, there are scenic vistas of densely-forested mountains.

A visit to the Great Wall is a pleasant way of ending a tour of Beijing.