Islamic State, the jihadist organization bent on establishing a caliphate in the Middle East, is being pounded relentlessly by the United States and its partners in a concerted military campaign to dislodge it from its bases in Iraq (torn by sectarian strife), Syria (bloodied by a civil war) and Libya (mired in anarchy).

The new American president, Donald Trump, is expected to pick up the pace of the offensive, which was initiated by his predecessor, Barack Obama. It’s possible that the United States and Russia, which is heavily invested in protecting the regime of President Bashar al-Assad of Syria, may join forces in combating Islamic State.

The drive against Islamic State, whose objective is to unseat the governments of Syria and Iraq, has unfolded in stages.

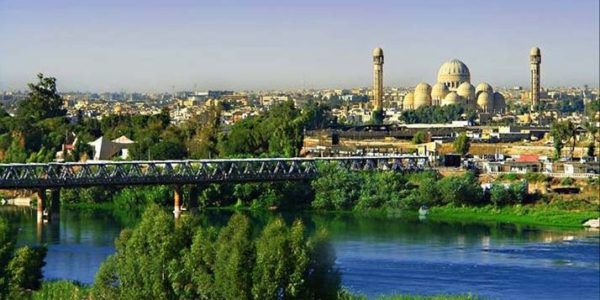

Last October, the Iraqi army, supported by U.S. air power and backed by Kurdish fighters and Iraqi Shiite militias, launched a major operation to retake Mosul, which fell to Islamic State in June 2014. Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, was captured by the Sunni jihadists after Iraqi soldiers retreated ignominiously, leaving their American weapons on the battlefield.

In the wake of its astonishing victory, Islamic State established its headquarters in Mosul — a Sunni majority city in a predominately Shiite nation — and imposed an austere form of Islam on the population. Women were requiring to cover up in public, smoking was banned and movie theatres were closed. And from the pulpit of Mosul’s Great Mosque, Islamic State’s bearded leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, once a member of Al Qaeda, officially declared a caliphate in Iraq and Syria.

With the launch of the Mosul campaign on October 17, Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi boasted that the Iraqi flag would be raised over the city “very soon.” This was an exercise in hyperbole, to say the least. Islamic State has put up fierce resistance, having deployed suicide bombers and chemical weapons, such as chlorine and sulphur mustard agents, to fend off attacks. But on January 18, two days before the Obama presidency ended, Iraqi forces seized the eastern half of Mosul.

It isn’t clear what role Iran played in the battles leading up to the seizure of eastern Mosul. But until now, Iran has provided Iraq, its next-door neighbor, with military advisers and perhaps even fighters. Strangely enough, Iran and the United States, which are at loggerheads over a variety of issues, are on the same side fighting a common enemy.

No one knows when the Iraqi government will attempt to capture the western part of Mosul, but the battles that lie ahead will likely be difficult. Islamic State, having already lost the Iraqi cities of Ramadi and Fallujah, will pull out all the stops to maintain its grip on Mosul. The city is important to Islamic State for practical and symbolic reasons. Mosul is very close to the lucrative oil fields on whose revenues it depends. Mosul’s tax base is a valuable source of income. Islamic State’s narrative of resistance to “infidels” might well be compromised should it be defeated in Mosul.

In the meantime, fighting is taking place on the approaches to the eastern Syrian city of Raqqa, the de facto headquarters of Islamic State. About a month after the fall of Mosul, a joint Arab-Kurdish force, augmented by U.S. aircraft and 300 American commandos, launched an attack to recapture Raqqa. The then U.S. secretary of defence, Ashton Carter, said its goal is to “isolate and ultimately liberate” Raqqa, which has been held by Islamic State for the past two and a half years.

The Raqqa campaign, however, is plagued by problems.

Turkey, a key participant, is annoyed that Syrian Kurds, backed by the United States, are playing a pivotal role. The Turkish government of Reccep Tayyip Erdogan is concerned that the Kurds may try to create an autonomous Kurdish enclave on its southern border and thereby embolden Kurds in Turkey to press for independence.

And if Raqqa is recaptured, the United States may find itself in an awkward position because that city may have to be returned to the authority of Assad, whose government Washington has so far opposed.

Islamic State is also absorbing body blows in Libya, which lies fragmented since its descent into civil war following the collapse of Mouamar Qaddafi’s authoritarian regime in 2011. Last winter, the United States began bombing Islamic State camps in Libya. U.S. jets, guided by American Special Operations personnel stationed there, bombed an Islamic State training camp outside the western town of Sabratha, killing some 43 trainees. Subsequently, Islamic State fighters were driven out of their coastal stronghold in Surt.

This past summer, the United States, operating from bases in neighbouring Tunisia, sent surveillance drones into Libya. Data gleaned from these flights indicated that Libya was still infested by Islamic State encampments. On January 19, a day before Trump’s inauguration in Washington, D.C., American B-2 bombers hit these camps, killing more than 80 fighters. It remains to be seen whether the United States will intensify its attacks in order to eradicate Islamic State’s presence in Libya.

Islamic State affiliates in Egypt and Syria, Sinai Province and the Yarmouk Martyrs Brigade, are also under attack, having been pummelled by the Egyptian and Israeli armed forces.

Egypt has been at war with Sinai Province since 2013. But two months ago, with Egypt’s apparent blessing, the Israeli Air Force carried out three air strikes against Sinai Province in the northern Sinai Peninsula, which Israel handed back to Egypt in the 1980s. Last November, in the first clash of its kind, the Israeli army killed four Yarmouk operatives on the Golan Heights, which Israel captured during the 1967 Six Day War.

On balance, Islamic State has come under increasing military pressure across the board. Since the United States and its allies launched air operations in Iraq and Syria in 2014, Islamic State has lost about half of its territory and upwards of 50,000 of its fighters, according to the Pentagon. Several of its senior leaders, ranging from Abu Mohammed al-Adnani, Islamic State’s chief spokesman, to Wa’il Adil Hassan Salman al-Fayad, its minister of information, have been killed.

These strikes have weakened Islamic State, but it’s still capable of mounting deadly operations. In the past 12 months, it has claimed responsibility for more than 30 terrorist incidents in 16 countries on four continents. Cities like Paris, Brussels, Ankara and Istanbul have borne the brunt of these attacks.

And in the Middle East, Islamic State is still a force to be reckoned with. Last December, Islamic State retook the Syrian city of Palmyra, nine months after Syrian and Russian forces recaptured it.

Islamic State is taking a beating at the hands of its enemies, but it’s far from dead and still poses a clear and present threat.