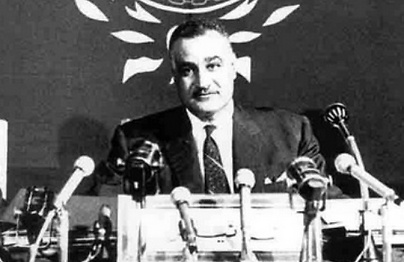

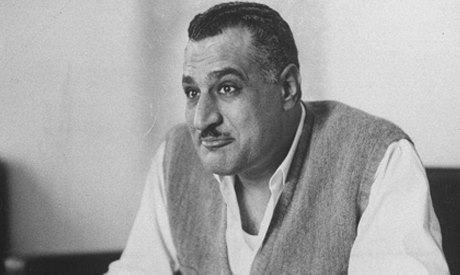

Egypt’s crushing defeat at the hands of Israel in the Six Day War created a crisis of confidence in the Egyptian government. Bouncing back from the depths of despair, President Gamal Abdul Nasser reacted to Israel’s victory by political and military means.

In Nasser’s Peace: Egypt’s Response to the 1967 War With Israel (Transaction Publishers), Michael Sharnoff, drawing on recently declassified primary sources, expertly examines his policies before and after that seminal conflict.

Sharnoff, an associate professor of Middle East Studies at the Daniel Morgan Graduate School of National Security, argues that Nasser’s view of the Arab-Israeli conflict gradually changed.

During the early 1950s, he was perceived by the United States and Britain as a moderate capable of reaching a peace agreement with Israel. Nasser, a former Egyptian army officer, told a British labor minister that he had no desire to destroy Israel, and that “the idea of throwing the Jews into the sea is propaganda.” Nasser and his cronies, having deposed the monarchy in 1952, were mainly concerned with consolidating their hold on Egypt and removing British colonial bases in the country.

But as Nasser jockeyed to become the preeminent leader of the Arab world and a leading figure in the non-aligned movement, he adopted an increasingly belligerent attitude toward Israel. He condemned it as an imperialist implant, described its existence as a crime against the Palestinians and called for its destruction.

In the early 1950s, however, he had no interest in engaging Israel in military combat. But from 1954 onward, he permitted Palestinian guerrillas in the Gaza Strip to launch cross-border raids into the Jewish state. They elicited Israeli reprisals, which, in turn, hardened Nasser’s outlook. Israel’s collusion with Britain and France in the 1956 invasion of Egypt was the last straw for Nasser.

Drawing ever closer to the Palestinian cause, Nasser was instrumental in the formation of the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1964. At an Arab summit, he handpicked Ahmad Shukeiri, a Saudi diplomat, as its first chairman. Nasser then denounced a speech by Tunisian President Habib Bourguiba suggesting that Arab states recognize Israel along the lines of the 1947 United Nations Palestine partition plan.

By the mid-1960s, Nasser was a hardliner — one of the champions of a Palestinian secular state in place of Israel. “I say there is no opportunity for a peaceful settlement with Israel,” he told an interviewer. “The only solution is to liberate Palestine by force.”

Through a series of miscalculations, he goaded Israel to launch a preemptive air strike on Egypt on the morning of June 5, 1967.

Almost immediately after Israel’s triumph of arms, Egypt’s small Jewish community was punished, with 800 Jews being arrested on conspiracy charges and their properties confiscated.

Mohammed Heikal, the editor of Al Ahram and Nasser’s confidant, falsely claimed that the United States and Britain had provided an “air umbrella” to assist Israel in its offensive. Nasser allowed his ministers to spread that lie, but in 1968 he retracted it.

The Soviet Union, Egypt’s ally and arms supplier, severed diplomatic relations with Israel during the war, yet the Soviets were critical of Nasser’s threats to destroy Israel. Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet leader, said: “One must say that the tendency of the Arabs to eliminate Israel was not correct.”

Brezhnev, though, pledged to help Egypt recover the Sinai Peninsula through diplomacy and supported Nasser’s demand for an unconditional Israeli withdrawal to the prewar boundaries without having to explicitly recognize Israel’s right to exist or sign a peace treaty with it. Israel’s four most important leaders — Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, Defence Minister Moshe Dayan, Labor Minister Yigal Allon and Foreign Minister Abba Eban — rejected that demand. The Israeli government let it be known that direct negotiations with Egypt were required to achieve peace.

Moscow also supported Nasser’s strategy of rebuilding Egypt’s armed forces with Soviet assistance in preparation for another possible war. But Soviet President Nikolai Podgorny warned Nasser that the Soviet Union would not agree to fight alongside Egypt because this could trigger a direct confrontation with the United States, writes Sharnoff.

In the wake of the war, Nasser toned down his rhetoric. Instead of advocating Israel’s liquidation, he called for “liquidating the traces of (its) aggression,” all in the service of gaining international sympathy and support. At one juncture, Sharnoff adds, he even appeared ready to recognize Israel in exchange for a full Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories, payment for property damages in Arab countries, and a pledge by Western countries to commit to a long-range economic development plan for Egypt.

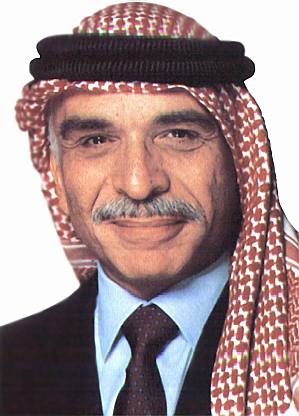

Nasser, in a significant shift, began focusing more on recovering the Sinai than on the Palestinian issue. But he told King Hussein of Jordan that, in the interests of regaining the West Bank, he would not object to his efforts to “make a separate agreement with Israel.”

Prospects for peace took a nosedive when Arab leaders at the 1967 Khartoum summit passed a resolution opposing peace with Israel, recognition of Israel or negotiations with Israel. To the Israelis, the Three No’s were further proof that the Arabs were not even remotely interested in peace. Shortly after the Khartoum resolution was unanimously adopted, Heikal wrote that the Arabs could accept a diplomatic solution of the Arab-Israeli dispute on condition that they would not have to recognize Israel, negotiate openly with it, abandon the Palestinian cause and allow Israeli ships passage through the Suez Canal.

In a commentary in Al-Ahram some two years later, Heikal upped the ante. As he wrote, “There is no room in the Middle East for Arab nationalism and Zionist nationalism…”

According to Sharnoff, Egypt neither accepted nor rejected United Nations resolution 242, which, among other things, called for the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the occupied territories, a just settlement of the Palestinian refugee problem and the “territorial inviolability and political independence of every state in the area.” Nasser claimed that the resolution required further study.

Nor did Egypt have much faith in the mission of United Nations envoy Gunnar Jarring, whose mandate was to implement resolution 242. In Heikal’s estimation, Jarring’s mission would benefit Egypt by providing time to prepare for another war.

“Egypt’s decision to engage in diplomacy was a calculated strategy to buy time in preparation for a future war,” says Sharnoff.

Indeed.

Egypt formally launched the War of Attrition against Israel in Sinai in 1968, although skirmishes and battles had already begun along the Suez Canal in the summer of 1967. Unfortunately, Sharnoff mentions that war only on passing. Egypt, in concert with Syria, started the Yom Kippur War 0n October 6, 1973.

In conclusion, Sharnoff is less than impressed by Nasser’s stance toward Israel.

As he puts it, “The real paradox of Nasser’s strategy is that while he possessed far more legitimacy than any other Arab leader to conclude a political settlement, he remained fearful of losing his leadership role.”

Until his untimely death in 1970, Sharnoff notes, Nasser sustained his leadership status in the Arab world by “placating the Arab masses with declarations of Egypt’s steadfast commitment to the (1952) revolution, pan-Arabism, Palestinian rights, and the eventual liquidation of Israel.”

On the eve of his passing, Nasser informed King Hussein that the destruction of Israel remained his ultimate goal. “I believe that we now have a duty to remove the aggressor from our land and to regain the Arab territories occupied by the Israelis,” he said. “We can then engage in a covert struggle to liberate the land of Palestine, to liberate Haifa and Jaffa.”

As Sharnoff suggests, Nasser’s rejectionism was a failure. “His unwillingness to compromise and formulate a coherent policy prevented Egypt from regaining its territory and dignity, principles that Nasser had so vigorously championed since assuming power.”

Nasser’s policy led to the War of Attrition, which would bring further devastation to Egypt. It was left to his successor, Anwar Sadat, to reclaim the Sinai by means of diplomacy.