Twenty five years after it was signed in Washington, D.C. by Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat, the Oslo peace accord has crumbled and ground to a complete halt. Widely regarded as a diplomatic breakthrough signifying the beginning of the end of Israel’s protracted conflict with the Palestinians, it aroused great expectations but was ultimately compromised by a plethora of problems.

Opposed by right-wing Israelis and by Palestinian Islamists and left-wing secular nationalists, Oslo was relentlessly battered by a succession of debilitating events.

Israeli and Palestinian extremists resorted to unbridled violence to derail it. Israel continued building settlements in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip so as to forestall the emergence of a contiguous and viable Palestinian state. Mainstream Palestinians accepted Israel’s existence, but not necessarily its legitimacy, and texts in Palestinian schools reflected that ambiguity.

As a result, there was a glaring absence of mutual trust, which may never be overcome.

Neither the Israelis nor the Palestinians got what they dearly wanted. Oslo did not usher in a shining new epoch of peace for Israel, though it did induce King Hussein of Jordan to forge a historic rapprochement in the form of a peace treaty with Israel. Nor did it provide the Palestinians with a sovereign and independent state they expected.

Disillusionment set in, pushing Israelis further to the right and Palestinians into the slough of moral despair and political rejectionism. In short, Oslo failed to meaningfully alter the status quo between Israel and the Palestinians.

From Camp David and Annapolis to Taba and Wye, Oslo produced a series of negotiations intended to move the process forward. These conferences achieved little or nothing and only solidified the perception in each camp that real peace was unattainable.

The sad reality is that the prospect of peaceful relations between Israel and the Palestinians seems as remote today as it was on the eve of Oslo.

Israelis carp that Oslo gave rise to a bloody Palestinian uprising, which erupted in 2000 and claimed the lives of more than 1,000 civilians and soldiers. Palestinians contend that Oslo perpetuated the Israeli occupation of the West Bank.

Born in a spirit of high hopes, Oslo consisted of two major components — the September 13, 1993 Declaration of Principles and the September 28, 1995 Oslo II agreement.

The Declaration of Principles, the product of secret diplomacy that blossomed into full-blown talks, broadly resulted in mutual recognition between Israel and the PLO, limited autonomy in Gaza and Jericho for the Palestinians during a five-year transitional period, and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority, a local police force and a legislative council.

Key final-status issues, from permanent borders to the Palestinian demand for a capital in East Jerusalem, would be deferred. Although Israel never explicitly promised the Palestinians statehood within the framework of a two-state solution, they assumed it was part and parcel of the Oslo deal.

Oslo II divided the West Bank into three zones — Area A, which is fully controlled by the Palestinian Authority; Area B, which is jointly administered by Israel and the Palestinians, and Area C, which is completely under Israel’s rule. Since about 60 percent of the West Bank is inside Area A, Israel is effectively in charge of it, much to the chagrin of Palestinians.

Oslo II also brought about security cooperation between Israel and the Palestinian Authority which continues to this day.

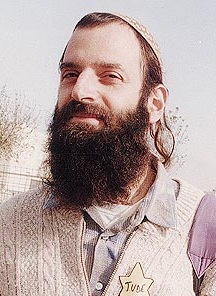

The entire process was shaken to its core in the winter of 1994 when Baruch Goldstein, an extremist who lived in a West Bank settlement, shot and killed 29 Palestinians in a mosque in Hebron. Goldstein, an American physician who had made aliya, was pummelled to death by a Palestinian mob. In the eyes of Palestinians, Goldstein’s rampage demanded revenge. Several months later, it was exacted when Hamas, an Islamic organization that calls for Israel’s destruction, launched a concerted campaign of suicide attacks that would plague Israel for years.

In the autumn of 1995, Yigal Amir, another Jewish extremist, assassinated Rabin in Tel Aviv. Shimon Peres, the foreign minister and one of Oslo’s architects, succeeded Rabin. Peres, who assumed he would win the 1996 general election, lost to Benjamin Netanyahu by a whisker. Netanyahu, the leader of the Likud Party who had vehemently railed against Oslo, slowed down the pace of talks with the Palestinians.

Under pressure from U.S. President Bill Clinton, though, Netanyahu agreed to relinquish 80 percent of Hebron to the Palestinian Authority, leaving the rest for Jewish settlers. Netanyahu, however, refused to abide by the terms of the Wye accord and made no further withdrawals from the West Bank.

Ehud Barak, the new Labor Party leader, trounced Netanyahu in the 1999 election. In 2000, at the Camp David summit organized by the United States, Barak offered Arafat substantial territorial concessions, but Arafat balked and the summit ended in abysmal failure.

Toward the end of September, Palestinian riots broke out in eastern Jerusalem, and within a few days, the second intifada was raging. Far more deadly than the first Palestinian rebellion, which broke out in 1987, it caused scores of deaths and soured a significant number of Israelis on the idea of peace with the Palestinians.

In 2002, following a massive suicide attack in Netanya, Israel invaded the West Bank in Operation Defensive Shield, reoccupying major Palestinian towns like Nablus and Hebron and dealing the peace process, such as it was, a devastating blow from which it never really recovered.

Arafat died in 2004. But long before his death, Israel had lost trust in him, claiming he was duplicitous and had not sufficiently cracked down on terrorism. His second-in-command, Mahmoud Abbas, the prime minister, replaced Arafat as president of the Palestinian Authority.

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, Israel started to build a security fence along the West Bank and, in 2005, withdrew unilaterally from Gaza and several settlements in the West Bank. But in 2006, Hamas defeated Fatah — the middle-of-the-road Palestinian faction — in elections in Gaza. In the following year, Hamas staged a violent coup, ousting Fatah altogether from Gaza. In short order, Hamas resumed firing rockets and mortars at Israeli communities adjacent to the border.

Israel’s response was fierce. In 2008, Israel launched the first of three border wars with Hamas and its sister organization, Islamic Jihad. Two other wars would erupt in 2012 and 2014, causing significant casualties and immense damage in Gaza.

Sharon’s successor, Ehud Olmert, tried to forge a peace agreement with Abbas and almost succeeded. But because Olmert was being investigated by the Israeli police for corruption, Abbas considered him a lame duck and withdrew from further negotiations.

Netanyahu returned to office in 2009 after a 10-year hiatus. Acceding to a request by U.S. President Barack Obama, he agreed to impose a partial freeze on settlement construction in the West Bank, but this move had no salutary effect on what was left of the peace process. At Washington’s urging, Israel entered into bilateral negotiations with the Palestinian Authority in 2013, but these discussions, which took place under the auspices of U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, crumbled and finally collapsed in 2014.

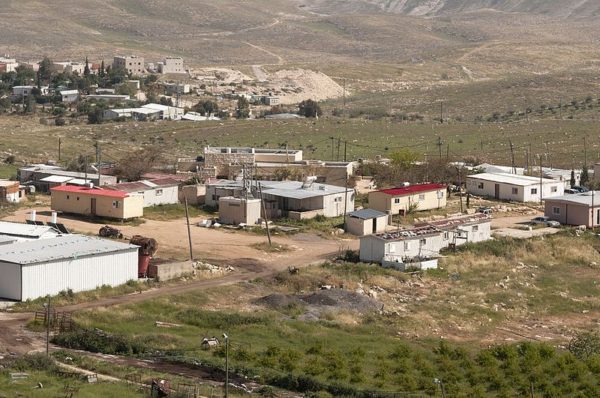

Presiding over the most right-wing government in Israel’s history, Netanyahu expanded the network of settlements in the West Bank and tolerated the presence of “illegal” outposts there. Since the advent of Oslo, the Jewish settler population in the West Bank has more than tripled.

Netanyahu paid lip service to a two-state solution from 2009 onwards. But emboldened by U.S. President Donald Trump’s strong pro-Israel policy, he has backed away from it. Netanyahu now contends that Israel has no partner in Abbas, who supports coexistence and rejects violence, but who has tolerated baseless Palestinian assertions that Jews have no historic links or claims to their homeland in Israel.

For a while, Oslo held out the possibility that Israel and the Palestinians were on the cusp of forming a new and positive relationship based on mutual interests. But after a quarter of a century of on-again, off-again talks and sporadic bloodshed, no such thing has happened, much to the detriment of both sides.