The death of the notorious Holocaust denier Robert Faurisson on October 21 at the age of 89 reminds us that this form of antisemitism has been a problem for quite a while.

I presented a paper on the subject, “Control of the Past as Control of the Future: Denials of the Holocaust,” at a conference at Ohio State University in Columbus way back in 1984.

Faurisson died, appropriately enough, in his hometown of Vichy. He was a staunch defender of Marshal Philippe Petain, the Vichy French leader who collaborated with the Nazi occupiers of the country during World War II.

A former professor of French literature at the University of Lyon, Faurisson maintained that the gas chambers in the Auschwitz death camp in Poland were the “biggest lie of the 20th century,” instead claiming that the deported Jews died of disease and malnutrition.

He also contested the authenticity of the diary of Anne Frank, the Jewish girl in Holland who managed to hide with her family from the Nazis for years before being caught and sent to concentration camps.

The colossal power of the official means of information has, until now, guaranteed the success of the lie and censured the freedom of expression of those who denounced the lie.

In a nutshell, this was the essence of Faurisson’s thesis:

Adolf Hitler’s gas chambers never existed and no genocide of the Jews ever took place. This lie, which was essentially of Zionist origin, permitted a gigantic political and financial fraud of which the State of Israel was the principal beneficiary, while the chief victims of this lie and this fraud were the German people and the Palestinian people.

Most Holocaust deniers have presented variations on that theme.

Faurisson was fined by a French court in 1983 for having declared that “Hitler never ordered nor permitted that anyone be killed by reason of his race or religion.”

Faurisson’s ideas were derived principally from a French pacifist named Paul Rassinier, who, in his 1964 book, Le drame des Juifs européens, contended that Germany’s conduct during the war was no worse than any other country’s — and that, in any case, the Jews were responsible for the war.

Rassinier corresponded with the American Holocaust denier Harry Elmer Barnes, who arranged for the translation of four of his books. In 1977, these were collectively published by Noontide Press under the title Debunking the Genocide Myth.

As for Faurisson, he revealed his skepticism of the Holocaust gas chambers in articles published in 1978 and 1979 in the French daily Le Monde. These became an embarrassment for the newspaper.

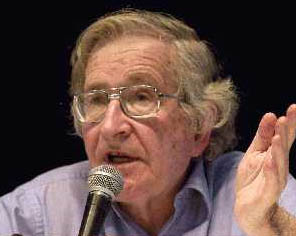

One of Faurisson’s works, in 1980, was published with an introduction by Noam Chomsky, who insisted that he wrote it as a defence of freedom of speech, including that of Faurisson. Chomsky was accused of supporting Faurisson, something he denied.

Faurisson also peddled his falsehoods in, among other venues, the Journal of Historical Review, a house organ of the California-based Institute of Historical Review, established in 1978 by Willis Carto. It ceased publication in 2002.

A four-volume collection of many of Faurisson’s revisionist writings, Écrits Révisionnistes (1974-1998), came out in 1999.

After France passed a law in 1990 making Holocaust denial a crime, Faurisson was repeatedly prosecuted and fined for his writings. He was dismissed from his academic post in 1991.

The most recent judgment against him came in November 2016, when a French court fined him 10,000 euros for propounding “negationism” in interviews published on the internet.

Other prominent Holocaust deniers have included Northwestern University professor Arthur Butz, who published The Hoax of the Twentieth Century in 1976. In Canada, James Keegstra and Ernst Zundel circulated Holocaust denial theories.

Holocaust denial is no longer only the preserve of European and North American fascists. It has migrated to the Middle East as well.

A press release by the Gaza Palestinian movement Hamas in April 2000 decried “the so-called Holocaust, which is an alleged and invented story with no basis.”

In August 2009, Hamas indicated that it would refuse to allow Palestinian children to study the Holocaust, which it called “a lie invented by the Zionists,” and referred to Holocaust education as a “war crime.”

In 2012, Faurisson himself received a prize from Iran’s president at the time, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, for his “courage, resistance and fighting spirit” in contesting the Holocaust.

In 2016, the Iranian regime exhibited over 150 cartoons that denied or mocked the Holocaust at the state-run Islamic Propaganda Organization in Tehran.

Among Iran’s ruling elite, Holocaust denial and the accompanying conspiracies about Jewish power are omnipresent and diverse.

Faurisson may be dead, but the malevolence he disseminated continues and spreads.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.