One of the wonders of the world, the Dead Sea, is dying a slow death. A horrible thought, but depressingly true.

Rich in medicinal minerals, like magnesium, the world’s saltiest, lowest-lying body of water has shrunk by about one-third and its depth has fallen by 65 feet. The Dead Sea has receded because it has not been replenished by its main source, the Sea of Galilee.

To make matters worse, sinkholes, 6,000 of them, have appeared along its shore and forced roads, businesses and date plantations to be closed. Appearing at a rate of 500 a year, sinkholes could affect the lucrative tourist industry in the Negev desert.

The spectre of a vanishing Dead Sea has concentrated minds in Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority, which all lay claim to parts of it. Efforts to stabilize and save it by means of a massive engineering plan, the Red Sea-Dead Sea Conveyance Project, are now under serious discussion.

But as Saving the Dead Sea, a PBS documentary to be broadcast on April 24 at 9 p.m. suggests, scientists are not in full agreement on its utility.

Under the ambitious proposal, a pipeline extending from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea would pump water to a desalination plant in Aqaba, Jordan. The filtered water would then be conveyed, via pipes, to the Dead Sea. The problem at present is that no one knows what effect Red Sea water would have on the Dead Sea.

Scientific experiments at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev have ascertained that treated Red Sea water might well turn the blue waters of the Dead Sea white or red, which would not be a satisfactory outcome.

Another problem is that desalination, an ingenious but costly method of purifying sea water into drinking water, could destroy the fragile coral reefs of the Red Sea.

This informative documentary, which includes interviews with Israeli, Jordanian and Palestinian scientists and officials, makes the persuasive argument that the incremental decline of the Dead Sea is nothing less than a “man-made disaster.”

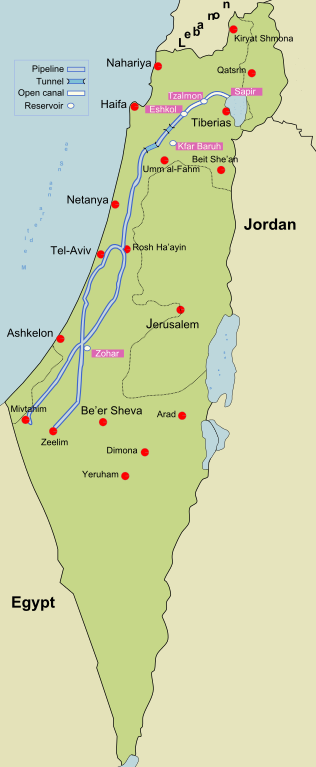

For centuries, the Dead Sea was replenished by water from the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River. But the construction of the National Water Carrier by Israel in the 1950s altered this dynamic to a significant degree.

Designed to pump water to Israel’s coastal plain and the parched Negev, the National Water Carrier — a flashpoint of conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors — deprived the Dead Sea of 96 percent of its water supply from the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River.

In this connection, the documentary raises an important question: why not restore the flow of water from the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea? The simple answer is that the declining volume of water in the Sea of Galilee is such that it is no longer capable of providing this essential service.

Potash mining, a major source of income for Israel and Jordan, has affected the Dead Sea adversely as well. Intent on developing this key export industry, both countries converted the southern segment of the Dead Sea into a massive evaporation pond, which is dependent on replenishment from the northern part of the Dead Sea. As a result, the northern portion of the Dead Sea has been diminished.

Saving the Dead Sea sets out the daunting challenges facing the Dead Sea now and in the future, but it is less clear about hard-and-fast solutions.