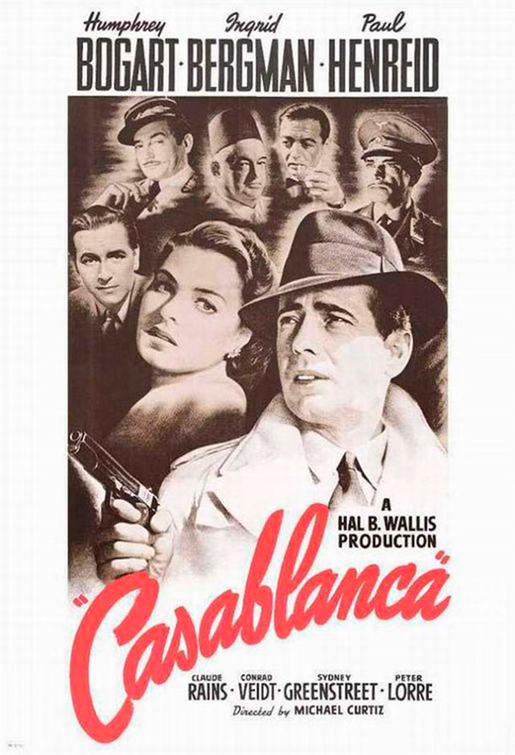

The 1942 Warner Brothers film, Casablanca, is a Hollywood classic. Starring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, this romantic drama won Academy Awards for best picture, best adapted screenplay and best director. Michael Curtiz, who directed it, was a Hungarian Jew who had a long list of movies to his credit, from The Adventures of Robin Hood to Yankee Doodle Dandy.

Curtiz, whose original name was Mano Kaminer, learned the craft in Europe and refined it in the United States after Jack Warner, the chairman of Warner Brothers, invited him to work in Los Angeles. Curtiz had impressed Warner with his visual style, which traced its roots to German Expressionism. Warner particularly liked Curtiz’s unusual camera angles and high crane shots.

Curtiz arrived in Hollywood in 1926 and never looked back, churning out films of every genre. His most enduring picture was probably Casablanca, which earned him, Bogart and Bergman a kind of cinematic immortality.

Tamas Yvan Topolanszky’s black-and-white feature film, Curtiz, which will be screened at the Toronto Jewish Festival on May 5 and May 7, is an imaginary foray into the making of Casablanca and a portrait of its director. It is supposedly inspired by true events.

It’s 1941 and Jack Warner (Andrew Hefler), the legendary mogul, is sitting in his office chatting with Curtiz (Ferenc Lengyel) and Johnson (Declan Hannigan), a U.S. government official. The United States, having entered World War II, needs rousing films to promote the war effort. Casablanca could well be one of those inspirational, and entertaining, pictures. Warner, being an American patriot, is only too happy to oblige, but he also demands a hit from Curtiz.

Curtiz is a hardboiled craftsman, but in the first few minutes of Topolanszky’s movie he comes across as a stereotypical sexual predator. Sitting in a cavernous studio, he seduces a 23-year-old waitress who enjoys the fleeting encounter as much as he does.

Fast-forwarding to 1942, the film introduces us to a new character, Kitty (Evelin Dobos). “Six o’clock in my room,” Curtiz tells the young lady. Is he arranging a date? Not in the least. Kitty is his estranged daughter whom he has not seen in years. She and her mother were brought to America from Hungary by Curtiz and now live in New York City. Curtiz is also trying to get his sister out of Hungary, whose Jewish citizens have been relegated to second-class citizenship by an antisemitic government politically and militarily aligned with Nazi Germany.

On the set of Casablanca, Curtis is a taskmaster. But he has no authority over Johnson, a hovering presence who annoys him. “With this film we’re going to win the war,” boasts Johnson.

To Johnson, Casablanca is supposed to be about hope and honor. But to Curtiz, a chain-smoking cosmopolitan who claims he’s “a man without a country,” a movie can’t be burdened with ideological baggage. Johnson, of course, doesn’t understand him. Later, Johnson admonishes Curtiz. “There can’t be uncertainty on whose side you’re on,” he says. “It’s us or them.”

This appears to be a minor issue compared to three others. Casablanca has fallen behind schedule and gone over budget, as studio bosses brusquely inform Curtiz. And no one, not even scriptwriters Julius and Philip Epstein (Yan Feldman and Rafael Feldman), has a clear idea how the film should end.

As if he does not have enough on his plate, Curtiz clashes with the actor Conrad Veidt, who plays a Nazi villain, and becomes embroiled in a heated discussion with his daughter, who feels neglected and shunned.

Lengyel and Dobos, both of whom are Hungarian actors, deliver strong performances as Curtiz and Kitty. The rest of the cast is quite good. The movie itself, shot in film noir style, is atmospheric and appealing.