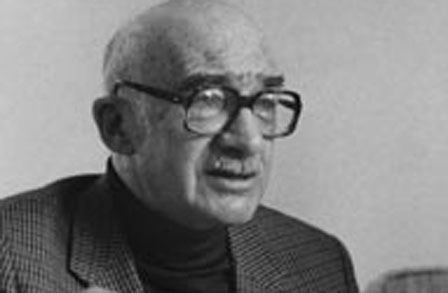

Aficionados of Yiddish language and culture will be drawn into Uri Barbash’s affectionate biopic of one of the greatest Yiddish poets of the 20th century, Avraham Sutzkever, who died in Tel Aviv in 2010 at the ripe old age of 96. Black Honey: The Life and Poetry of Avraham Sutzkever, which will be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival on May 3 and May 9, portrays him as a person for whom the written word was not only paramount but a matter of life and death.

Barbash’s documentary, a melange of file footage, vintage photographs and talking heads, is set before, during and after the Holocaust, a catastrophe that tested Sutzkever’s strength and resolve to the utmost.

A citizen of the Soviet Union, he spent his first years in Siberia, and was raised in Vilna — a hub of Jewish learning — after his father’s premature death. A member of the Young Vilna poetic group, he impressed his peers as a sophisticated poet of immense talent.

With the German occupation of Lithuania in the summer of 1941, Jews were confined to a six-block ghetto. Within six months, two-thirds of its inhabitants, including Sutzkever’s mother, were murdered in the nearby Ponary forest.

Such was the misery in the ghetto that he and his wife, Friedke, poisoned their infant son because there was no way he could survive under such brutal conditions.

As Barbash suggests, poetry saved his own life, giving him the inner strength to feel like a free man and survive as the world around him crumbled into ash and dust. He wrote every day, buoyed by the conviction that the Germans could destroy everything but the words he put to paper.

Sutzkever was a member of the Nazis’ Paper Brigade, whose task was to assemble a cache of books, Jewish classics, for a planned German museum about Jewish civilization in Frankfurt. He and his fellow archivists sabotaged the project, hiding the most most valuable books and handing over the rest to the Germans.

In September 1943, he and his wife fled the ghetto and joined a band of partisans in the forest. At the behest of the Moscow-based Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, the Soviet government mounted two attempts to rescue him. The first Soviet aircraft that tried to pluck him out of the Nazi-infested region where he was in hiding was shot down by German forces. The second airplane managed to land and flew him to Moscow.

At the request of the Soviet government, Sutzkever testified at the 1946 Nuremberg trial of Nazi war criminals, delivering a methodical account of German atrocities in Vilna.

Sutzkever and his wife settled in Palestine on the eve of the first Arab-Israeli war in 1947. The new Hebraic state of Israel was not fertile ground for planting the seeds of a Yiddish revival, but Sutzkever was undeterred. With the assistance of the Histadrut labor union, he founded Die Goldene Keyt (The Golden Chain), which would develop into one of the world’s finest Yiddish literary journals.

Sutzkever performed his mission in Tel Aviv brilliantly, but was always aware that Yiddish in Israel would always play second fiddle to Hebrew, except in Ashkenazic ultra-Orthodox anti-Zionist circles.