The “Fourth Reich” is an emotive slogan that conjures up diametrically different meanings.

Originally a rallying cry for anti-Nazi resistance following the emergence of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, the Fourth Reich was a progressive slogan promising a hopeful post-Nazi future. German Jewish refugees who had fled Germany after Hitler’s accession to power in 1933 were especially fond of it. But after Germany’s ignominious defeat in World War II, the Fourth Reich took on a new and menacing meaning revolving around fears of a Nazi/fascist resurgence in West Germany.

In The Fourth Reich: The Specter of Nazism From World War II To The Present (Cambridge University Press), the American scholar Gavriel D. Rosenfeld deftly examines this slogan in all its variations, while reminding us that it was never more than a theoretical construct in post-war German history.

Rosenfeld, a professor of history at Fairfield University and a specialist in the Third Reich, begins his erudite exploration of this complex issue by referring to Phantom Victory, a dystopian novel by the American-based Austrian writer Erwin Lessner published in 1944. Set between 1945 and 1960, it’s about a charismatic man who replaces Hitler as the new fuhrer and tries to lead Germany to world domination. “Phantom Victory reflected growing concerns that the dangers of the recent past might return in the near future,” writes Rosenfeld.

After the war, Europeans, in particular, were beset by angst about unrepentant Nazis returning to office and creating a Fourth Reich. As he puts it, “These anxieties (were) expressed not only in novels like Lessner’s, but in political jeremiads, journalistic exposes, mainstream films, prime-time television shows, and popular comic books.”

In the United States, the specter of a Fourth Reich was popularized by the novelist Robert Ludlum in his best-selling 1978 novel, The Holcroft Covenant.

These fears have come and gone, but have remained exclusively in the imagination.

In reality, Nazism was irretrievably crushed in 1945, and it posed no serious threat either to capitalist West Germany or communist East Germany. Yet in the early years of West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer’s administration, fears of renazification surfaced, precipitated by the rise of the neo-Nazi Socialist Reich Party, the discovery of a plot by a senior Nazi official to oust Adenauer’s democratic government, and the eruption of a wave of antisemitic swastika daubings on synagogues.

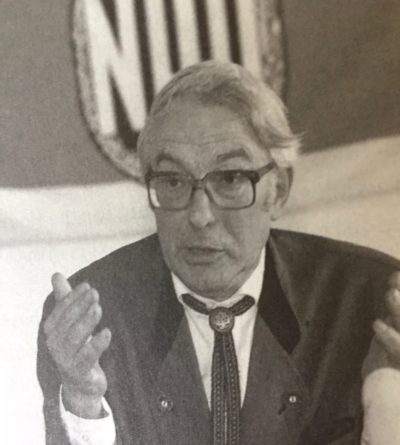

Also fanning concerns about a Nazi revival were the rise of the far-right National Democratic Party in the 1960s and the subsequent appearance of neo-Nazi demagogues like Manfred Roeder and Michael Kuhnen.

Before elaborating on his theme, Rosenfeld explains the origins of the slogan “Third Reich.” During World War I, it occasionally appeared in a pacifist context. But after Germany’s surrender in 1918, conservative and volkisch Germans, like the author Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, argued that a radical response was necessary to meet an unprecedented crisis. He outlined his concept in The Third Reich, published in 1923.

The right-wing poet and founding member of the Nazi Party, Dietrich Eckart, endowed the Third Reich with an antisemitic cast, while the Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg invoked “the rising Third Reich” in his Myth of the Twentieth Century. During the 1920s, Hitler hardly ever referred to the Third Reich, but this changed after President Paul von Hindenburg appointed him chancellor.

With the Nazis firmly in charge, German emigres such as the Bavarian aristocrat Prince Hubertus zu Lowenstein promoted the idea of a “post-Nazi Fourth Reich” as an alternative to the Third Reich. Supporters of the Fourth Reich also hailed from left-liberal circles. As an example, Rosenfeld cites Georg Bernhard, a journalist and former parliamentarian.

German Jewish emigres like Bernard were hopeful that the Third Reich would collapse and be replaced by a democratic, humanistic and egalitarian Fourth Reich. During the war, Carl Goerdeler, the former mayor of Leipzig and a Nazi opponent, was widely regarded as Hitler’s successor in a new Germany. During the same period, the Nazi regime cynically equated the Fourth Reich with Allied plans to crush and subjugate Germany.

With the onset of the post-1945 Allied occupation of Germany, some observers continued to associate the Fourth Reich with a progressive model of statehood. Still others, linking it to a resurrected Third Reich, portrayed Germany as a nation beholden to the destructive traditions of militarism, imperialism and nationalism. Sefton Delmer, a correspondent for the Daily Express, Britain’s largest newspaper, wrote that the “spirit of the swastika” was returning to Germany and threatening to call forth “the Nazi that lurks in every German’s heart.” The novelist Thomas Mann was pessimistic as well, forecasting that West Germany would soon degenerate into “a fully fascist” state.

As Rosenfeld points out, pessimists like Delmer and Mann were proven wrong by virtue of the creation of the democratic Federal Republic of Germany, with Adenauer at its helm. “Alarmists clearly exaggerated the danger that denazification posed to the country,” says Rosenfeld, adding that West Germany in the 1950s was never at risk at being replaced by a Fourth Reich.

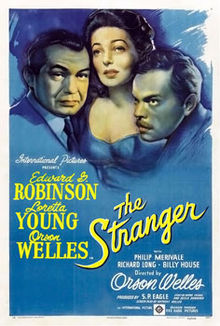

Nevertheless, fears of a Nazi revival were reflected in postwar American films like The Stranger, directed by Orson Welles and starring Edward G. Robinson as U.S. investigator attempting to track down a Nazi war criminal in hiding in small-town America.

The rise of neo-Nazi parties amplified concerns that West Germany was heading in the wrong direction. As an example, Rosenfeld cites the German Reich Party, which demanded a restoration of Germany’s pre-1939 borders.

Fuel was added to the fire when half a dozen prominent ex-Nazis were arrested in 1953, charged with plotting to overthrow the government. The leader of the plot was the former state secretary of the Ministry of Propaganda, Werner Naumann.

The presence of ex-Nazis in Adenauer’s government caused apprehension too. Among these dubious figures were the director of the Federal Chancellory, Hans Globke; the minister of refugees, Theodore Oberlander, and the minister for housing, Victor Preusker.

Adenauer’s policy of integrating former Nazis into the West German state was a deliberate one, expressly designed to sideline neo-Nazis. As Rosenfeld writes, “He offered right-leaning voters a simple, if strict, deal: the new West German government would forgive them for supporting the Third Reich by approving a generous amnesty program that would allow them to find employment in the postwar Federal Republic. In exchange, ex-Nazis had to abandon their allegiance to Nazi ideas and commit themselves firmly to democracy.”

Many former members of the Nazi party, he notes, eagerly accepted Adenauer’s offer.

The eruption of anti-Jewish vandalism in late 1959 and early 1960, known as the swastika wave, stoked fears that a reactionary Fourth Reich was in the offing.

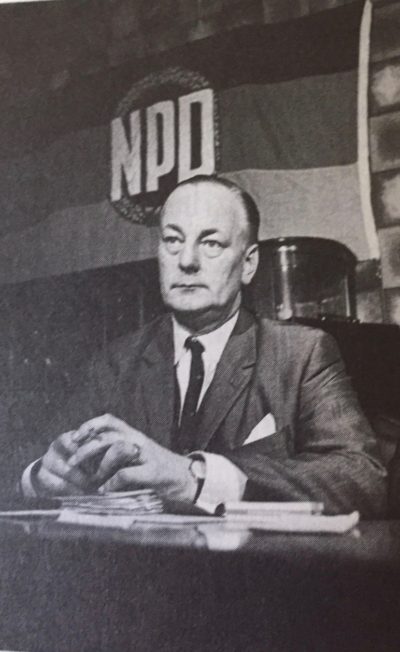

During the mid-1960s, the emergence of the far-right National Democratic Party, led by former Nazi Adolf von Thadden, aroused further trepidation that neo-Nazism was rearing its ugly head. The party’s leaders routinely minimized the number of Jews murdered in the Holocaust, rejected the continuation of war crime trials and opposed the payment of reparations to Israel.

The flight of Nazis to Argentina, a nation with a substantial German immigrant community, reinforced the perception that a revival of Nazism was a distinct possibility. Rosenfeld deflates this theory: “Of the tens of thousands of German immigrants who left for Argentina after the war, only a small percentage (2-3 percent) were Nazis, and no more than a few dozen were war criminals.”

The emergence of a new generation of right-wing extremists in the 1970s and 1980s fanned fears that West Germany was susceptible to Nazism. Manfred Roeder, the founder of the German Action Groups, launched a series of bombings against various targets, including a Jewish school in Hamburg. Michael Kuhnen called for a grand alliance of European and Islamic countries against “Zionism, capitalism and communism.”

German reunification in 1990, the outbreak of neo-Nazi violence against foreign guest workers, the presence of asylum seekers, and the demise of communism in the late 1990s provided yet more fodder for pundits claiming that a fascist Fourth Reich was imminent.

More latterly, the election of Donald Trump as U.S. president has unleashed a torrent of references to the Fourth Reich. And as Rosenfeld says, anti-Zionists have used this slogan to defame Israel.

As he reminds us, it’s a slogan that rightists, centrists and leftists can deploy to advance their respective agendas.