Germans during the Nazi era were “the targets of the most vigorous, lucid and sophisticated public relations campaign ever conjured up in all of history,” writes Nicholas O’Shaughnessy in his substantive work, Marketing the Third Reich: Persuasion, Packaging and Propaganda (Routledge), which follows on the heels of his first volume, Selling Hitler: Propaganda and the Nazi Brand.

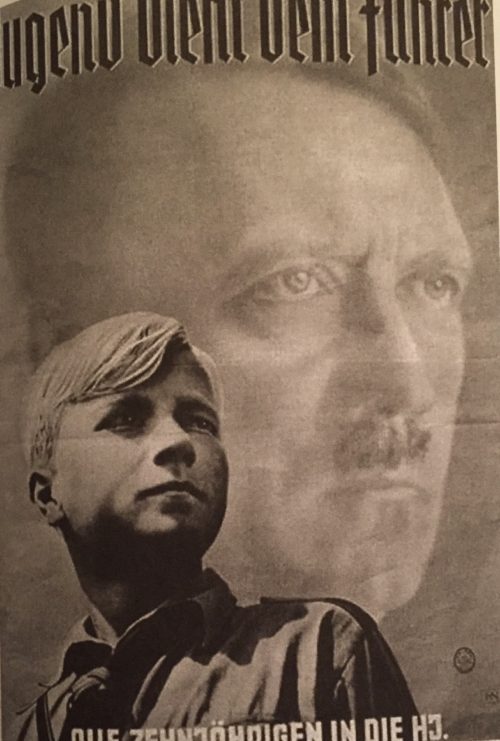

As he persuasively claims, Adolf Hitler’s propaganda machine from its earliest days recognized the value of marketing, while Nazism itself was a “brand,” with the swastika as its emblem and phrases like “Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Fuhrer” as one of its slogans.

The Nazi usage of symbols, mythology and rituals blended with the romantic and neo-classical traditions to produce a new reality fay different from either, says O’Shaughnessy, a professor of communications at Queen Mary University in London.

He argues that the Nazis were greatly influenced both by their ally, Benito Mussolini’s Italian fascist movement, and by their ideological enemy, Joseph Stalin’s Communist regime. From the Italians, the Nazis learned the art of spectacle and public theater. From the Bolsheviks, they absorbed the importance of discipline, meticulous organization and gimmickry.

Joseph Goebbels was the master puppeteer, though he was exclusively responsible for only two jurisdictions, film and radio, which were extremely crucial in promoting Nazism, a “secular nationalist religion,” in O’Shaughnessy’s view.

For the Nazis, radio was the single most important means of mass communications. In 1932, the year before Hitler’s accession as chancellor, there were 4.2 million radios in Germany, but by 1938 radio ownership had more than doubled to 9.6 million. Recognizing its importance, Hitler became the first politician to make major use of radio. Open to new technology, the Nazi government started the second regular television service after Britain’s BBC.

The film industry during the short-lived Weimar Republic had been a world leader, producing movies ranging from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to The Blue Angel. Under the Nazis, cinema became a very significant component of what O’Shaughnessy describes as “regime projection.” Of the 150 to 200 films distributed annually in Germany from 1933 to 1939, slightly more than half were German. “The best Nazi films are of equivalent quality to the good Hollywood films of their generation,” he notes.

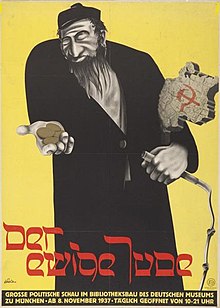

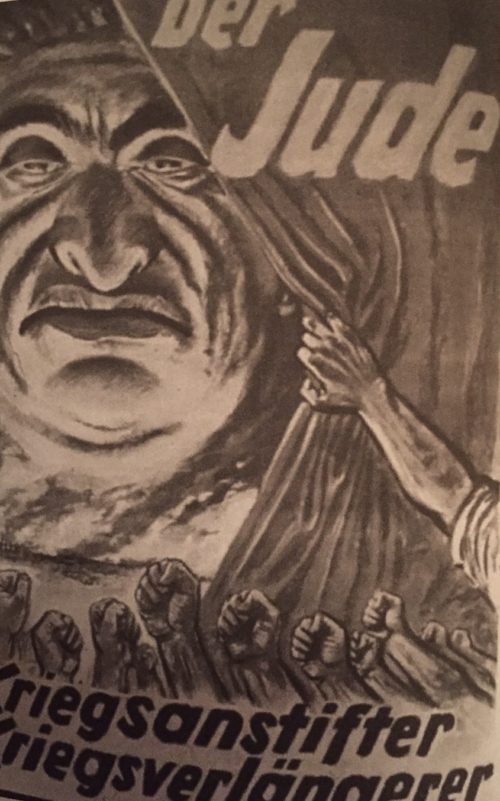

While the focus of these movies was usually on escapism, overtly propaganda films were also churned out. These included Kolberg, a 1945 period piece designed to rally morale when the war already had been lost, and three undisguised antisemitic films, Jew Suss, The Rothschilds and The Eternal Jew, the third having been the most disgusting of the lot.

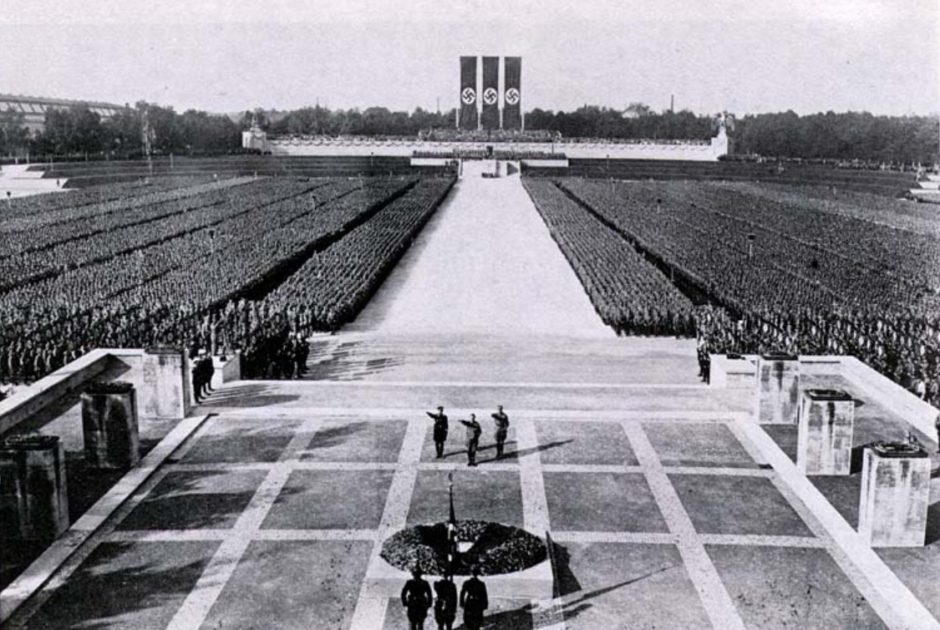

Documentaries and newsreels were another key component of Nazi propaganda. Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will was a stunning visual record of the 1934 Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg, setting new standards in cinematography. Films such as Campaign in Poland and Stukas conveyed an image of war compatible with Nazi objectives.

Nazi rallies, like grand operas, were exercises in pageantry. To Goebbels, they perpetuated “the Fuhrer myth” and Hitler’s “halo of infallibility.”

Nazi newspapers, posters, leaflets and even children’s books also played their respective parts in rallying public support for the regime. “Antisemitism in much of the mainstream media was less visible than we might imagine,” he says. But Julius Streicher’s Der Sturmer catered to ideologically antisemitic German readers.

Illustrated magazines, an idiosyncratic blend of consumerism and frivolity, conveyed the overarching Nazi message as well. As an example, O’Shaughnessy cites Signal, a visually impressive magazine of color photographs and breathless prose that presented German forces in occupied territories not as conquerors but as friends.

Music, an integral element of Nazi packaging, too, was “expressive of an aesthetic of martial heroism,” he says.

Being “tart and smart,” Nazi propaganda took flight in 1936 when Germany hosted the winter and summer Olympic Games. “They revealed just how far perceptions of reality can be managed, and the willingness of people to prefer the elation of falsehood to the sobriety of truth,” he succinctly observes.

Riefenstahl’s documentary, Olympiad, a cinematic tribute to the summer Games in Berlin, was emblematic of the Nazis’ success in winning hearts and minds.

Whether peddling athletic greatness, antisemitism or territorial aggrandizement, the Nazis were master marketeers. Marketing the Third Reich makes this very clear in strong and cogent prose.