New Jewish immigrants arriving in the United States in the first years of the 20th century usually settled in big northern cities like New York, Philadelphia and Boston or in nearby smaller towns. Scarcely any went to, say, Mississippi, an antebellum southern state defined by the strictures of segregation and populated by a very small number of Jews.

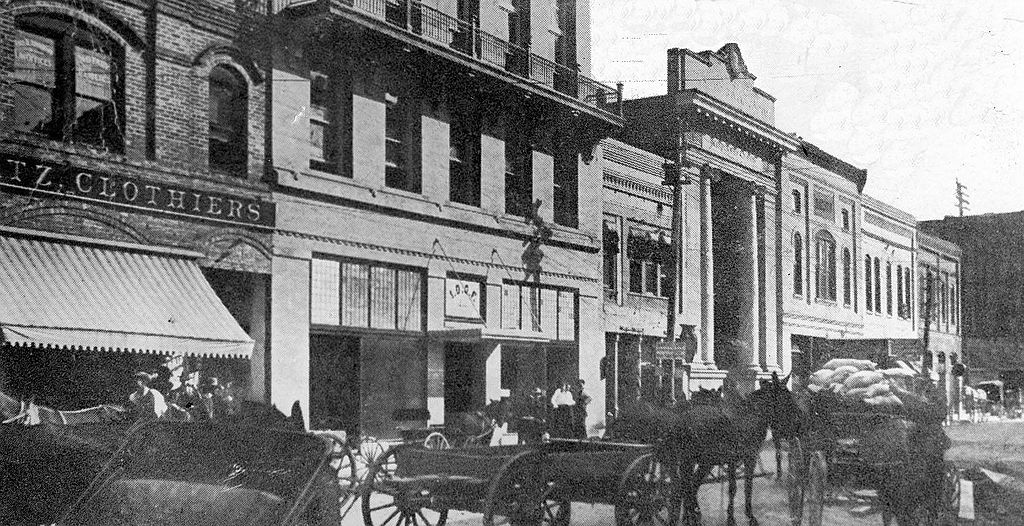

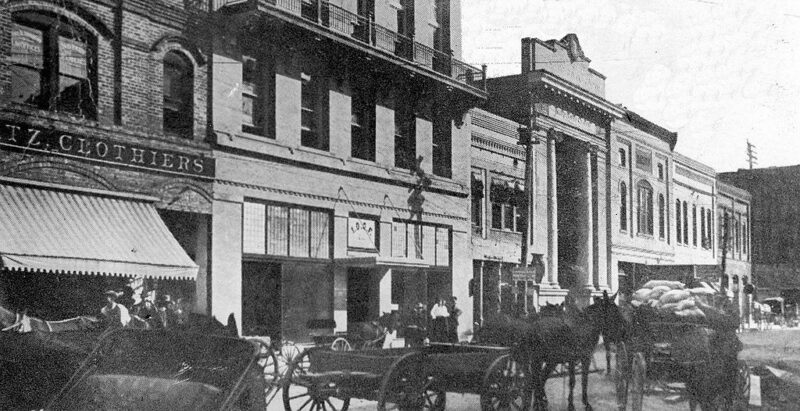

Leon Waldoff’s father, Paul, was one of the very few newcomers who set down roots in Mississippi, which I visited along with my younger daughter nearly a decade ago. A Russian Jew, he arrived in the southeastern town of Hattiesburg in 1924, when it was home to about 30 Jewish families. Earning a livelihood as a peddler, he soon bought a clothing store, one of six owned by Jewish merchants in Hattiesburg, founded in 1882 by William Harris Hardy, a Confederate army captain and veteran of the U.S. Civil War.

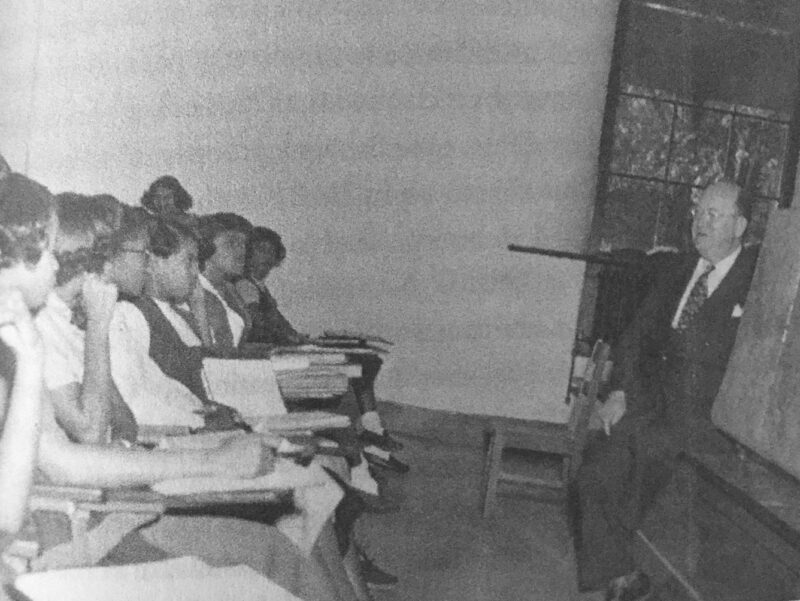

Waldoff, a professor emeritus of English at the University of Illinois, has written a fine account of his youth in Hattiesburg. A Story of Jewish Experience in Mississippi (Academic Studies Press) covers a lot of ground. A profile of a remote Jewish community, it is also an examination of race relations during the Jim Crow era and the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

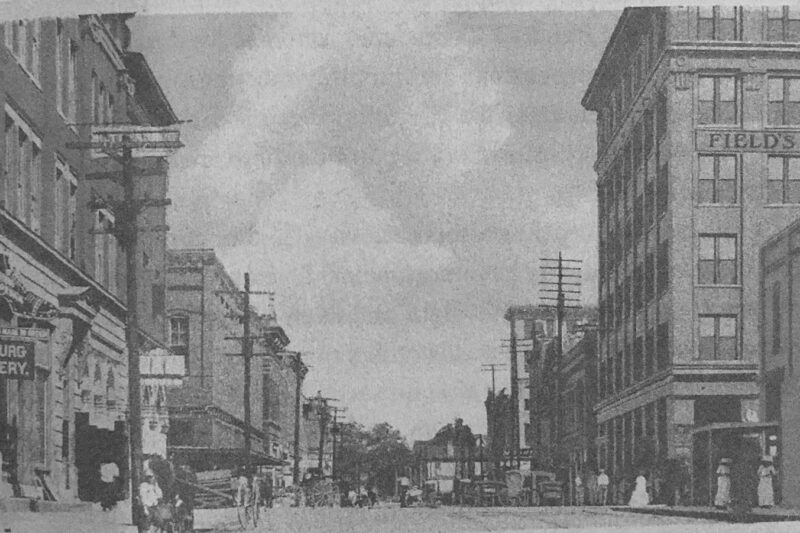

By Waldoff’s reckoning, the first Jewish settlers gravitated to Hattiesburg — a center of the lumber industry and a railway hub — in the late 19th century. Maurice Dreyfus, one of the earliest Jewish inhabitants, founded a lumber mill in 1900 and operated it until 1923. By then, the town’s population had more than tripled to 13,270. Hattiesburg continued to grow, with the population reaching 29,000 in 1949, of whom some 150 were Jewish.

Waldoff’s father was persuaded to try out Hattiesburg by his uncle and aunt, who lived there. Carrying his merchandise in a pack on his back and a suitcase in one hand, he sold goods from dresses and blouses to belts and needles.

Legions of Jewish peddlers from Germany, France and the Austro-Hungarian Empire had preceded him. They settled in the Delta region, where cotton was king, and in towns like Clarksdale, Greenville, Vicksburg, Cleveland and Canton. Still others went further afield, ending up in Jackson, Natchez and Meridian.

Like all newcomers, Waldoff’s father, a Yiddish speaker, was required to learn and internalize local customs regarding race. “He had to be sensitive to the prejudices of whites and the feelings of blacks while trying to communicate in a language still strange to him,” he writes. “In Russia, he had lived under the tsarist government’s antisemitic policies … but now he found himself on the other side, a part of the white population that reserved the most important civil rights for itself …”

“He took things as he found them,” he adds. “His focus was on making a living and achieving financial independence and security.”

In short, his father’s generation of immigrants had no desire to challenge the status quo or rock the boat. “Among the many customs of segregation my father had to deal with … was the reluctance of white customers to buy a dress or shirt … that a black customer had tried on.”

According to Waldoff, African Americans generally welcomed Jewish peddlers, not only because they treated them with courtesy but also because they provided a certain degree of freedom in shopping. For probably this reason, blacks usually saw Jews in a more positive light than white Christians. On the other hand, as he notes, African American attitudes were shaped, in part, by antisemitic myths and folklore and the perception that Jews were an integral component of the white supremacist system that oppressed blacks in southern states.

Waldoff, who was born in 1935, admits he was so “blinded” by segregationist culture that he remained unaware of the daily humiliations to which blacks were subjected, particularly in the first half of the last century.

“I remember going to a minstrel show when I was a teenager and seeing the black-faced white men on the stage and hearing the roars of laughter in the white audience surrounding me,” he recalls. “I laughed at the puns and jokes and enjoyed the songs, still blind to the racist nature of all the merriment.”

As he points out, Jews in Hattiesburg attempted to shed the mantle of “otherness” so as not to be regarded as “aliens.”

“We didn’t think of ourselves as being so different,” says Waldoff. In the main, Jews were accepted by their fellow whites, but until the 1960s certain country clubs, with few exceptions, banned them from membership. In his view, the Jewish community won greater acceptance in the mid-1930s when it hired Arthur Brodey, a Reform rabbi from Canada, to be its spiritual leader.

Several years before his arrival, the community was thrown in anxiety when a local Jewish boy, in tandem with a black man, committed a robbery that resulted in the death of a white male. The incident reminded Jewish residents of the angst that had gripped Atlanta’s Jewish community before Leo Frank was lynched by a mob in 1915 and after one of its synagogue was fire bombed in 1958.

The civil rights movement, which took the form of demonstrations, sit-ins, voter registration drives and freedom rides, alarmed southern Jewish communities because Jewish students from northern states and rabbis from both the north and the south were active participants.

“Jews would find themselves exposed to intimidation and violence,” he says, citing the involvement of White Citizen’s Councils and the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in attempting to staunch the tide of desegregation.

Rabbi Charles Mantinband, who took up his duties in Hattiesburg in 1951, was among the rabbis who denounced segregation. His outspokenness aroused antipathy from some congregants. “They wanted him to remain silent on the subject of civil rights,” Waldoff says. Feeling the pressure, Mantinband left Mississippi in 1963. His successor, David Ben-Ami, also proved to be too liberal for the membership. He was sacked after less than a year on the job.

Synagogues in Jackson and Meridian were bombed in the 1960s, as was the home of Jackson’s resident rabbi, Perry Nussbaum, a Canadian who was urged to vacate his post and leave. “For decades, the Klan had used terrorism against Negroes,” he notes. “Now it was being used against Jews.”

In desperation, Jackson’s Jewish community appealed to “outside Jewish busybodies” to stay away, lest its security and welfare be jeopardized.

A minority of southern Jews supported the segregationist system and joined White Citizen’s Councils. One such member wrote an essay in favor of segregation, criticizing the B’nai B’rith for its support of the civil rights campaign.

As Waldoff looks back at that turbulent period, he recognizes that “the silence about segregation was a feature of everyday life when I was growing up. Segregation wasn’t a topic of discussion in our home or in school or among my friends … Silence on that subject had become second nature.”

Quoting the historian Clive Webb, Waldoff observes that “a pervasive sense of fear seized Jews throughout the south,” and that the fear reinforced the silence.

This fearful and troubling epoch has receded into the past. The problem today is one of demographics. Jewish old timers have passed on and some their children have left the small towns, leaving their respective communities depleted. Membership in Hattiesburg’s congregation is down to about 30 families, a far cry from the days when the future seemed brighter.

As for Waldoff, he has not lived in Hattiesburg for decades.