Most Americans would scratch their heads in puzzlement if asked what role the Federal Reserve, the U.S. central bank, plays in the powerhouse American economy. The Fed, as it’s colloquially called, is indeed extremely important — controlling the money supply, setting interest rates, regulating banks and, in general, keeping a watchful eye on things.

Formed just over a century ago, in response to the financial crisis of 1907, the Fed is also enormously influential outside the United States because the almighty U.S. dollar has been the world’s primary reserve currency since the seminal Bretton Woods conference of 1944. The global financial system, therefore, is dependent, for better or worse, on the decisions of the Fed.

So, whether or not you’re familiar with its inner workings, you should know something about the Fed. It may affect your job, your mortgage, your pension, your savings.

Jim Bruce’s illuminating documentary, Money for Nothing: Inside the Federal Reserve, which opens in Toronto’s Bloor Hot Docs Cinema on Friday, Feb. 21, may just be the primer you’re looking for.

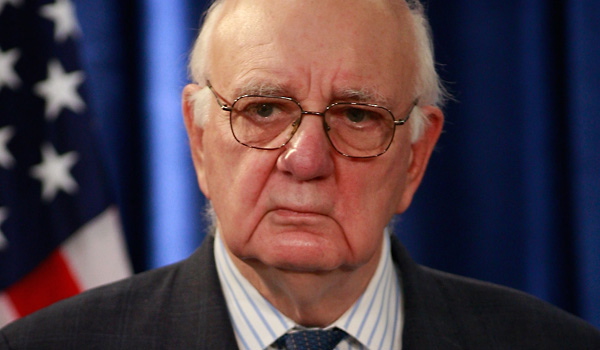

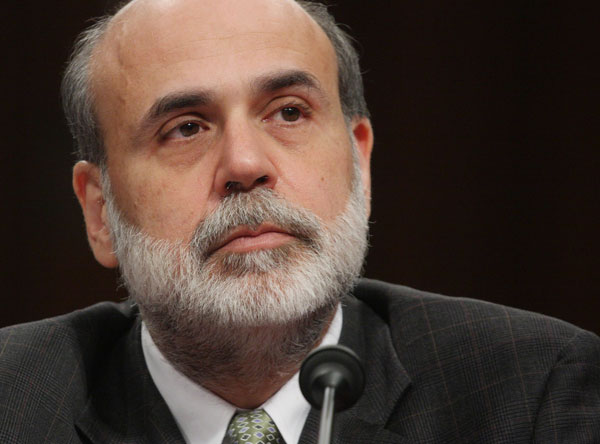

Billed as the first film of its kind, and narrated in stentorian tones by the actor Liev Schreiber, it draws strength from a tightly-written script and from interviews with current and former Fed officials such as Janet Yellen (its present chairperson), Paul Volcker, Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke, economists, stock market traders, investors and business historians and journalists. You can learn more at Stocktrades.

The panic of 1907, which resulted in the collapse of scores of banks, was “the straw that broke the camel’s back,” says one observer. According to Yellen, the Fed, plus its web of 12 reserve banks, were established with the express purpose of providing “liquidity” for the financial system.

And while it has had a steadying influence, it has not always anticipated crises, claims Alice Rivlin, a former deputy chair of the Fed. It did not foresee the meltdown of 2008, which brought the U.S. economy to the brink of utter disaster and whose effects we’re still feeling. And the Fed was, in part, responsible for the Great Depression of the 1930s due to its reckless manipulation of interest rates. One economist ascribes its failure to its reluctance to abandon old and outmoded ideas.

Bruce claims that Volcker restored faith in the U.S. dollar after it had lost half of its value in the 1970s, and credits him with having steered the American economy into a long period of prosperity from the mid-1980s onward.

“This was the golden age for the Fed,” says an economist.

Bruce devotes considerable air time to one of the Fed’s most influential chairmen, Greenspan, a disciple of Ayn Rand and a libertarian. Handling the 1987 stock market crash with finesse and aplomb, he slashed interest rates and engineered a soft landing for the economy. He then presided over a stock market and investment boom.

Greenspan, having witnessed the sharp fall of stock market and real estate values in Japan, expressed concern that the boom was really a bubble that could burst. Nonetheless, he refused to cool over heated stock prices and resisted calls to regulate the derivatives market, which, some say, was at the root of the 1987 crash. Since he considered regulation obsolete, he allowed stocks and the residential housing market to become overvalued.

Massive borrowing, at artificially low interest rates, precipitated the mortgage crisis of 2008. The Fed, we’re told, could have stopped irresponsible lending practices, but opted for a laissez-faire approach instead.

Greenspan’s successor, Bernanke, continued with his questionable policies, not believing that housing prices would decline so precipitously. He had faith in “market efficiency.”

In passing, the film chronicles the downfall of Lehman Brothers, a bastion of Wall Street, and the Fed’s $1 trillion-plus stimulus packages, which probably saved the U.S. economy from doom.

Looking ahead, Bruce argues that the Fed, which holds the future of the global economic system in its hands, must find a way forward to break the boom/bust cycle of capitalism.

Easier said than done.