The future status of the West Bank is a bone of contention in contemporary Israel, dividing friends and families along diametrically opposing lines. Some Israelis would give up all or parts of it in the interests of achieving a peace treaty with the Palestinians, who comprise the vast majority of its population. Still others, a vocal minority, claim it belongs to Israel and the Jewish people and should never be relinquished, even for the sake of peace.

The debate that has animated Israeli politics for nearly 50 years now began with Israel’s capture of the West Bank in the 1967 Six Day War. Known as Judea and Samaria to the religious nationalist camp in Israel, the West Bank was wrested from Jordan, which had held it since the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

To Israeli author Yossi Klein Halevi, Israel’s conquest of East Jerusalem, accomplished by the 55th Paratroopers Reserve Brigade, was “the most transcendent moment” of the Six Day War. By capturing the eastern sector of Jerusalem, inhabited until then by a mix of Palestinian Muslims and Christians and Armenians, Israel reunited Jerusalem, albeit artificially, and gained access to Jewish holy sites, notably the Western Wall, the last standing remnant of the ancient Jewish temple.

The soldiers in the 55th Brigade consisted largely of secular kibbutzniks, with a second group composed of religious Zionists. Resolutely united during the battle for eastern Jerusalem, they parted ways, politically at least, in the wake of the war. Convinced that Israel’s triumphant victory presaged the coming of the redemption, the religious among them became the vanguard of a movement to build settlements in the West Bank. The kibbutzniks, in turn, were among the founders of the peace movement, which opposed the construction of these outposts.

Klein’s book, Like Dreamers: The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation, published by HarperCollins, examines this schism through the lives of seven of the 2,000 soldiers who fought with the 55th Brigade.

In writing about this historic period, Halevi vividly recreates the tense atmosphere in Israel before the war and recalls the change in military orders that altered the destiny of the 55th Brigade. Originally assigned to fight the Egyptians in the Sinai Peninsula, the 55th was dispatched to Jerusalem and placed under the commander of the central front, Gen. Uzi Narkiss.

Its mission, Narkiss said, was to break through the formidable barrier of Jordanian trenches and minefields separating eastern and western Jerusalem, reach the Israeli enclave on Mount Scopus and, possibly, take the Old City, from which Jews had been expelled.

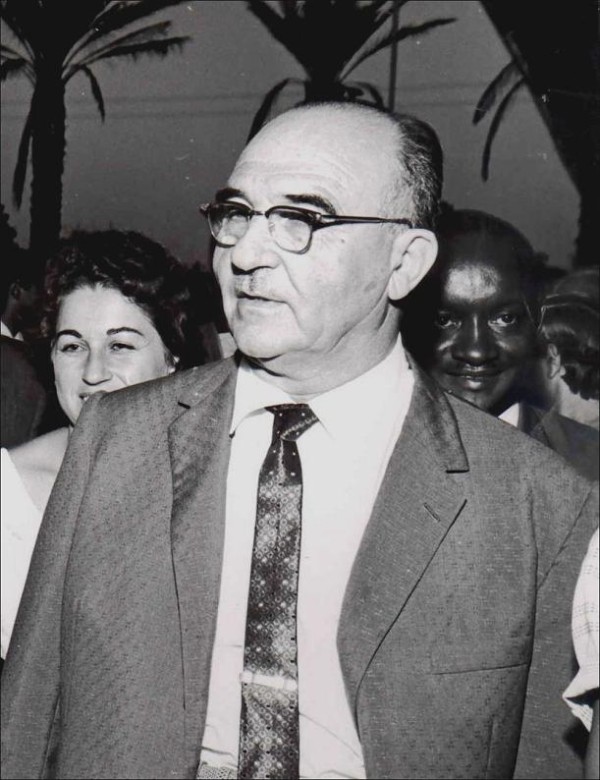

As Halevi reminds a reader, the Israeli cabinet was deeply divided over the issue of taking the Old City. Hawkish cabinet ministers like Menachem Begin insisted that Israel had an obligation to capture it, but cautious ministers, several from the National Religious Party, demurred. The prime minister, Levi Eshkol, was ambivalent.

The hawks prevailed, but the battle for eastern Jerusalem was a difficult one with respect to Israeli casualties. With the war having been won, Israelis rejoiced in an outpouring of national pride and hubris, momentarily forgetting the painful death toll that had been the price of Israel’s astonishing feat of arms.

Having put the situation on the ground in perspective, Halevi draws portraits of the soldiers of the 55th Brigade. He introduces us to Israelis like Yoel Ben-Nun, a founder of the Gush Emunim settlement movement in the West Bank; Hanan Porat, who founded the first Jewish outpost in the West Bank, Kfar Etzion, and Udi Adiv, a left-wing kibbutznik who railed against settlements and indeed Zionism.

As Halevi points out, Bin-Nun and Porat were both heavily influenced by Rabbi Zvi Yehudah Kook, the head of a major yeshiva in Jerusalem who fervently believed that Israel’s victory was preordained by a higher authority and that it should remain in the occupied territories and not trade them in exchange for peace.

The settlers were so adamant that the prime minister of the day, Yitzhak Rabin, accused Gush Emunim of trying to topple his government. Its leaders countered with the argument that there was nothing more sacred in the Zionist ethos than settling the land. By dint of fierce determination and cunning stealth, they persuaded a succession of Israeli governments to build a web of settlements throughout the West Bank, a policy that has isolated Israel.

Porat, a dreamer, justified his ideology on the basis of history. “Zionism is, in its essence, the fulfillment of the dream of generations,” he declared.

Bin-Nun was equally messianic, but eventually, he came to the conclusion that the right-wing dream of greater Israel, as well as the left-wing dream of Peace Now, were delusions. Israel needed to find a consensus, he thought.

Adiv, a member of Kibbutz Gan Shmuel, which had been built on the ruins of the Arab village of Cherkas, reached very different conclusions.

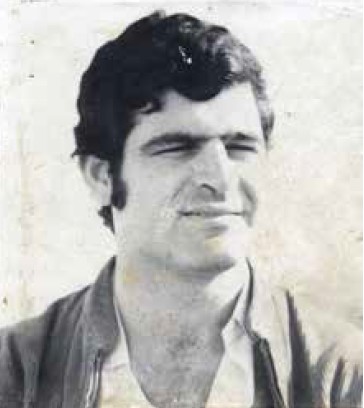

Believing that Zionism was a form of colonialism, he joined Matzpen, a tiny anti-Zionist group that supported the Palestinian national cause as a catalyst for revolution in the Middle East. A proponent of a binational state, with a Jewish minority, Adiv was recruited by an Israeli Arab under false pretences to work for Syria’s intelligence service.

Sentenced to a 17-year prison term, he was released in 1985 after serving 12-and-a-half years. Having renounced his youthful mistakes, he earned a BA degree in Middle Eastern studies from Tel Aviv University and landed a teaching job at the Open University in Haifa.

In closing, Halevi succinctly recaps the impact of the Six Day War on Israel: “It created a country caught in a paradox: Goliath to the Palestinians but David to the Arab and Muslim worlds; the only democracy that was a long-term occupier, and the only country marked by neighbors for disappearance.”

Clearly, the legacy of that war still burns brightly.