Roughly 130,000 German and Austrian Jews immigrated to the United States from 1933 until 1945. Victims of Nazi oppression, they struggled to adjust to a new society as they learned English, adapted to different customs and looked for jobs.

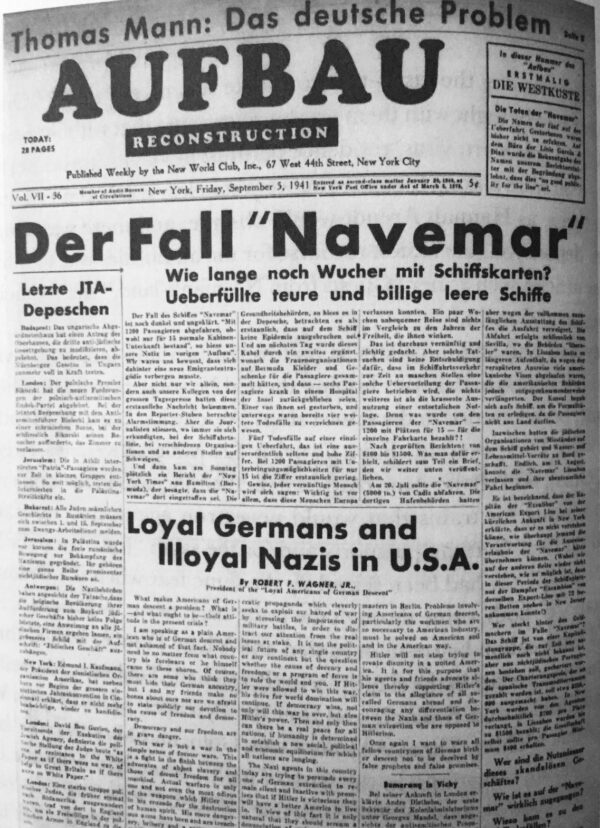

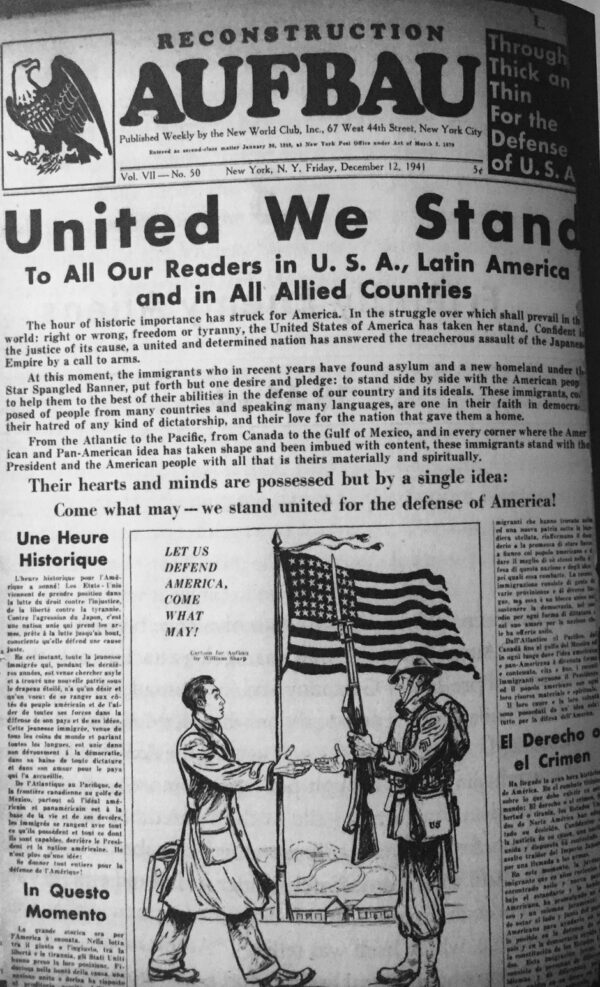

For many of these emigres, particularly in New York City, the German-language newspaper Aufbau was a major avenue into American life and an incubator of Americanization. Reaching 41,000 subscribers at its height just after World War II, Aufbau was central to the concerns and culture of its readers and helped them attain “spiritual and material shelter against the storms of the time,” as its longtime editor, Manfred George, put it.

Peter Schrag, a German Jewish immigrant who arrived in New York with his parents in June 1941, has written a first-class account of the role that Aufbau played in the lives of the new immigrants. In The World of Aufbau: Hitler’s Refugees in America (The University of Wisconsin Press), he explains how it served as a bridge between two worlds and how it reflected the values and priorities of its readership.

As Schrag acknowledges, a number of academic studies have appeared on Aufbau, including a PhD dissertation produced by Dagobert Broh at Concordia University in Montreal. “But no one, to my knowledge, has used the paper itself as a window into or as a guide to the generation of German-speaking immigrants to which it was addressed during the seventy years of its publication,” he says.

Schrag is not only a meticulous researcher, but an accomplished writer, and thanks to these skills he succeeds in drawing a vivid portrait of this vibrant community in exile.

The German and Austrian Jews who settled in America from 1933 onward were not like the “huddled masses” who arrived at Ellis Island in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with barely a penny to their names. Distinctly middle and upper-class in orientation, they ranged in occupation from former proprietors of department stores and shopkeepers to clerks and cabaret musicians.

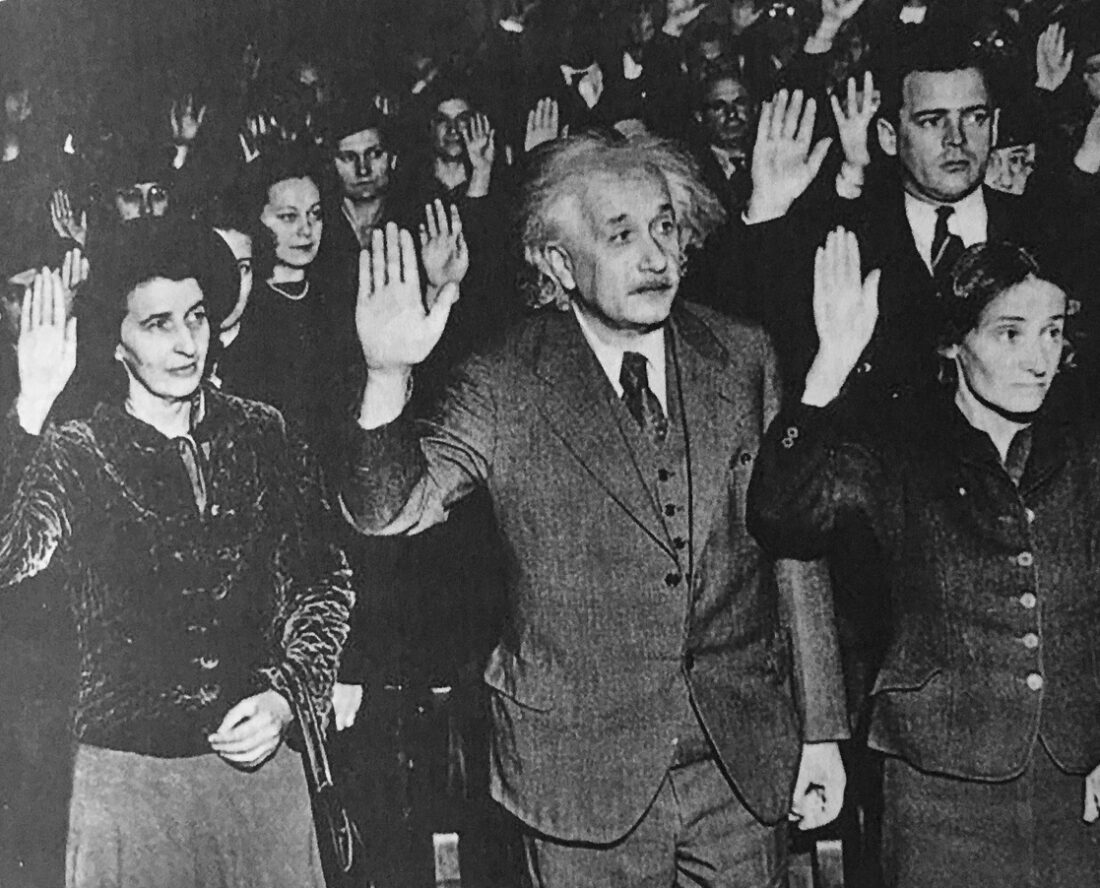

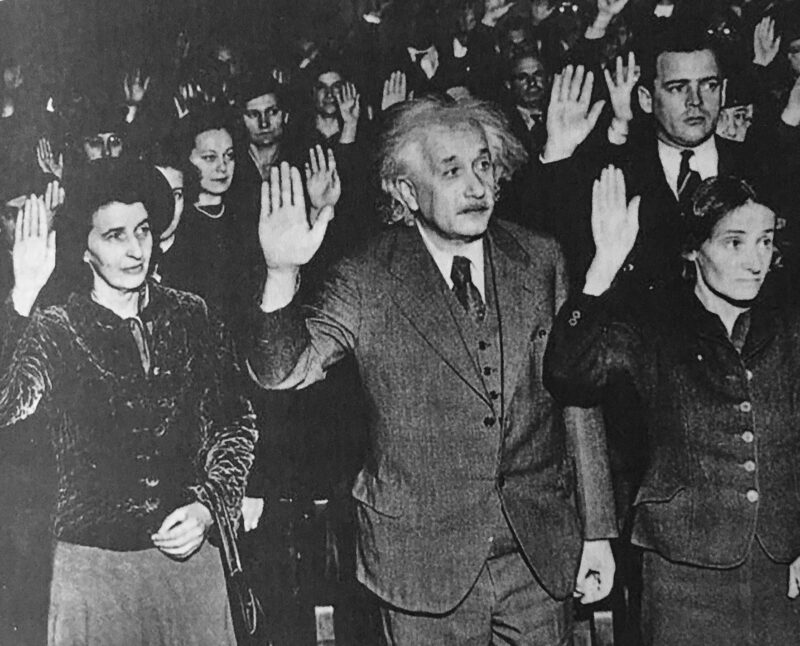

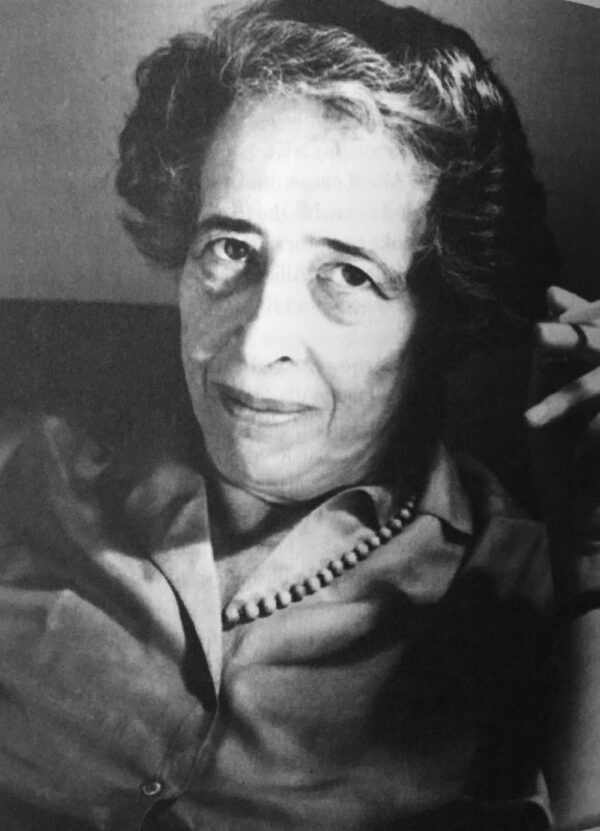

The luminaries among them included the scientist Albert Einstein, the novelist Alfred Doblin, the musician Fritz Kreisler, the conductor Bruno Walter, the movie director Billy Wilder, the political theorist Hannah Arendt, and the actor Peter Lorre.

For the most part, they were ordinary people whose lives had been abruptly upended by Adolf Hitler’s regime. Only after they had been uprooted by the Nazis did they truly realize that the fabled German-Jewish symbiosis had been little more than a mirage that existed mostly in the minds of Jews.

Aufbau, founded in 1934 as an occasional newsletter of the German-Jewish Club in New York, successively evolved into a monthly, a fortnightly and a weekly under a string of editors. Although it was widely read around the country, it was a small newspaper compared to the Jewish Daily Forward, a Yiddish broadsheet with a circulation of about 150,000 by the late 1930s.

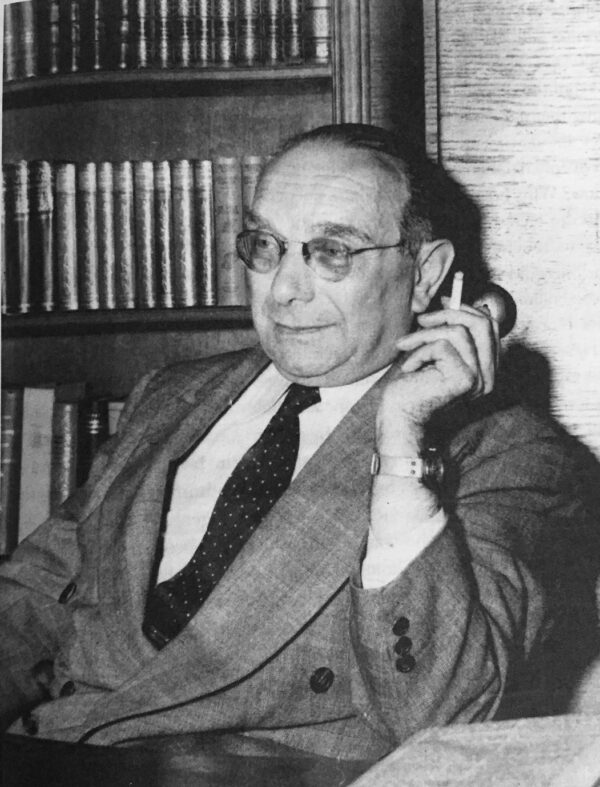

Manfred George, who had been a liberal journalist and theater critic in Weimar Germany, was appointed Aufbau’s editor in 1939, a year after his arrival in America. He remained at the helm until his death in 1965.

Published mostly in German, with a sprinkling of articles in English, Aufbau was largely staffed by journalists and administrative and sales personnel from Germany and Austria. Apart from its own stories, it carried dispatches and political cartoons from wire services and the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Renowned newcomers like the novelists Franz Werfel and Thomas Mann, one of its chief patrons, contributed pieces.

Banned in Germany, it was hardly the only newspaper of its kind in the city. Aufbau’s chief competitor, New Yorker Staats-Zeitung und Herold, was read primarily by German gentiles in Yorkville, a neighborhood in Manhattan. It vacillated between describing Germany as a “friendly nation” and condemning the Nazi persecution of Jews.

Consisting of 30 to 40 pages, Aufbau covered a wide variety of news topics, from the plight of Jews in Germany to the current situation in Mandate Palestine, to which tens of thousands of German Jews had fled. Aufbau also printed book, concert, film and theater reviews, advice columns, articles about U.S. immigration policy, and tips on American English pronunciation.

Celebrating American virtues such as democracy, religious tolerance and civil liberties, Aufbau encouraged its readers to Americanize themselves. At the same time, it dedicated itself to “saving the values of our European past from destruction.”

More than most newspapers, Aufbau instinctively understood what the stakes were for Europe’s Jews following Germany’s invasion of Poland. And yet, prior to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, when Washington hewed to a policy of neutrality, Aufbau avoided calling on the United States to enter the war. Schrag speculates that Aufbau was sensitive to “the possibility of an antisemitic backlash against ‘war-mongering'” Jews.

Antisemitism was deeply entrenched in the United States in the 1930s and 1940s, as he notes. “It was still a country where Jews couldn’t become partners in Wall Street law firms or sit on the boards of major corporations. It was a country where a lot of housing was restricted.”

And while Aufbau was careful not to take sides in domestic politics, it left little doubt that it strongly supported President Franklin Roosevelt and the Democratic Party.

U.S. immigration restrictions limited the admission of German Jewish refugees, but Aufbau took pains not to be too critical of this exclusionary policy.

Until the 1960s, Aufbau’s readers clustered on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, far from the Lower East Side, to which countless Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe had gravitated much earlier in the century and before. Some lived in cold water flats or in rooms in the Washington Heights neighborhood, which became known as the Fourth Reich and Frankfurt on the Hudson. Henry Kissinger, a future U.S. Secretary of State, lived there as a boy, as did Max Frankel, who would become the editor of The New York Times.

Still others settled down in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Forest Hills (where many apartment buildings were still reserved for Christians), Long Island and northern New Jersey. Clusters of German Jewish refugees lived in San Francisco and Los Angeles as well.

The majority of the refugees were hard-pressed to accommodate themselves to their new homeland. Rabbi Alfred Gottschalk, the former president of the Hebrew Union College, described them as “fish out of our linguistic, economic and cultural waters.”

Many were small business owners, artisans, mechanics, furriers, tailors and diamond cutters who had been forbidden to take their assets out of Germany and who were dirt poor when they landed in the United States. “Inevitably they were shocked by a loss of status almost as great, and more sudden, than the one that hit them when the Nazis came to power,” says Schrag.

He adds that many rediscovered their Jewish identity, which had been buried under their “German cosmopolitanism.”

Much to their dismay, the U.S. government classified them as “enemy aliens,” prompting a distinguished group of emigres to appeal to Roosevelt to drop that label. The attorney-general subsequently assured them they were aliens only in the “technical sense of the word.”

Despite being labelled as potential enemies, a disproportionate percentage of able-bodied refugees joined the U.S. armed forces. Schrag believes the figure was 30,000.

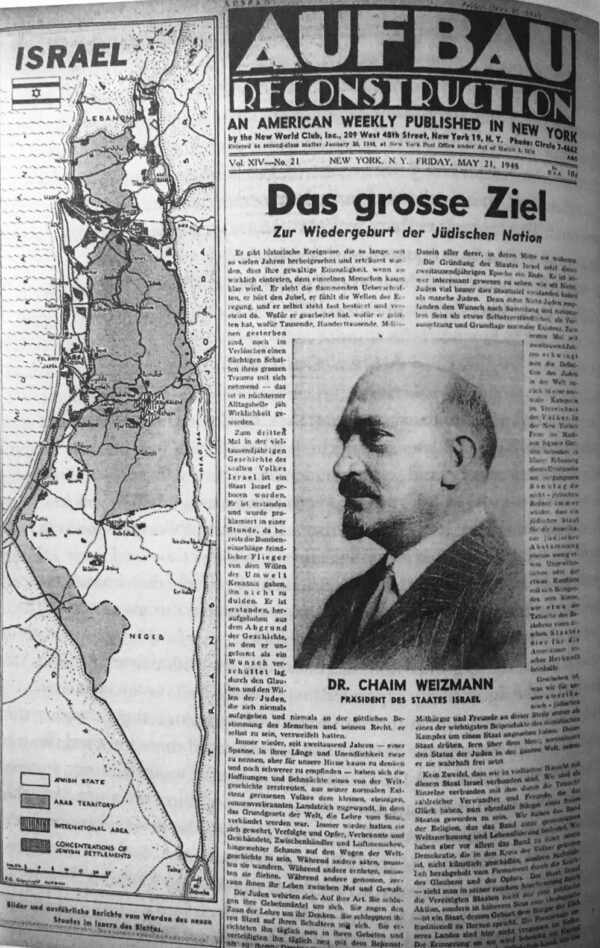

As the war raged, Aufbau paid increasing attention to events in Palestine. When Israel declared statehood, Aufbau allotted ten pages to its founding.

During the war and the postwar period, Aufbau carried a multitude of stories about the Holocaust and the Nuremberg war crimes trial. It was uneasy with Allied efforts to establish an economically revived and ultimately remilitarized West German state as a bulwark against the Soviet Union. Aufbau ran indignant pieces about former Nazis who held important positions in West Germany, and called for a program of restitution payments to refugees and survivors.

From the 1970s onward, Aufbau’s circulation declined incrementally as the generation of refugees gradually died. In the face of this stark reality, it reduced its publication schedule and, for a time, depended on support from the West German government, which bought large numbers of subscriptions to keep it going.”But the demographics were unavoidable,” says Schrag.

Although a significant proportion of its readers wanted nothing to do with postwar Germany, some visited the land of their forefathers, occasionally at the invitation of cities which had created special tourist programs for them. By then, West Germany, as opposed to communist East Germany, had become a prosperous state and had been integrated into the Western military alliance.

Toward the end of Aufgau’s existence, tellingly enough, none of its final editors were refugees and one, Monika Ziegler, was not even Jewish. Bought by a Jewish media company in Zurich in 2004, it was renamed Aufbau: The Jewish Monthly Magazine, a left-leaning, handsomely-illustrated periodical that ran articles on a broad range of global issues in both German and English.

In closing, Schrag concedes there is no reliable way to measure the influence that these refugees, Aufbau’s lifeblood, exerted on American culture. But due to their urbanity and cosmopolitanism, they “were able to penetrate American society more effectively and more rapidly than many other immigrant groups,” he quotes the historian Manfred Jonas as saying. “They quickly appeared in … the arts, the media, and the universities,” and were influential in helping purge the United States of its provincialism and xenophobia.

They certainly had an impact, and Aufbau channeled their energies in the right direction.